Alex Stone takes us on a kayak or dinghy trip to the heart of Waiheke Island, the arms of Pūtiki Bay.

If you tie your long hair back, and bundle it on top of your head, it’s called a pūtiki. A topknot. Pūtiki is both a verb – to tie something up, to tie into a topknot – and a noun – a knot or a bundle or a topknot. And that’s a nice point to begin exploring the natural and cultural history of Waiheke’s mother of all bays.

There’s so much history bundled up here, and much of it knotted up, for Pūtiki Bay has always encompassed contested sites, lending credence to the opinion that a true Waiheke Islander can enter an empty room – and get an argument going.

First landfall at Pūtiki Bay already finds us deep in drama. The lovely, pōhutukawa-fringed little bay just inside Kennedy Point and below the leading light (white, in an arc from Motuihe to Te Whau Point), is history. It’s loveliness that is.

Despite ongoing protests, construction of a marina accommodating 186 boats, and a floating carpark, has begun. The locals who had boats there all opted for the ‘eviction incentive’ ($14,000) and shifted their moorings elsewhere.

The rock mole and the wharf and slipway for the car ferry were built in 2005, and 1971 respectively. The marina is being constructed to the south of the mole.

Waiheke’s resident historian Paul Monin wrote: “Kennedy Point (originally spelt Kennedy’s Point or ‘Kay Pee’ for short) emerged as an alternative to the old Ostend Wharf site in the early 1960s, initially used to meet the need for vehicular services. Until then, the occasional motor vehicle had arrived on the island by barge to Ostend or Matiatia.

Oyster pickers at work in Pūtiki Bay around 1912

Though exposed to prevailing winds, Kennedy Point offered clearer access to deep water. The Waiheke Road Board shifted its attention to the Kay Pee alternative, ‘secretively,’ according to the Waiheke resident.

“Passenger services to Ostend ended in early 1965. Ostend Wharf reopened as a cargo port a few months later and saw some service until it was displaced by cargo services at Kennedy Point in 1971. It was demolished in 1981.”

At the time the Roads Board was optimistically planning for a population of 30-40,000 for Waiheke. Building Kennedy Point Wharf nearly bankrupted them.

Picnickers and holiday makers arriving at Ostend, 1922

A few hundred metres further on, just inside a rocky noname reef, there’s Kennedy Bay. This was the site of Waiheke’s second, but biggest shipyard.

The 16-ton schooner Thistle was built here by Henry Niccol – launched 1843 and wrecked in the Solomon Islands 1984. Then in 1883 Captain John Brown Kennedy bought 1,820ha of land here to establish Esslin Farm. He became the postmaster for Pūtiki Bay, and would take outgoing mail to steamers, rowing in his 18ft longboat. A grand homestead Dunesslin was built in 1907, but demolished in the 1950s when the pilings rotted away.

The next inlet has Shelly Beach at its head, also known as Putaki Bay. There was a disused oyster farm on the west side of Shelley Beach. Te Matuku Oysters is busy re-vitalising this oyster farm and will look at the remnants of another further up in Anzac Bay. Duana Upchurch told me they will be replacing the current structures, installing a more modern, sustainable method of oyster farming where the baskets are suspended above the sea floor.

Wharetana Bay Homestead

On the hill above Putaki Bay is Goldies Vineyard. The conventional story of the success of Waiheke wines starts with Jeanette and Kim Goldwater buying the land and setting up the vineyard in the 1970s. But that’s not the whole story. Wiremu Hoete grew grapes in Okoka Bay in the mid-1800s, and there had been a vineyard in Ostend since 1929.

A Croatian family outfit – headed by patriarch Lovre ‘Lorrie’ Gradiska – made fairly potent sherries and ports from hybrid vines, which were known on the island as ‘Purple Death.’ Their production ended with Lorrie’s death in the 1950s. Purple Death was a “fairly ferocious fortified brew”. Goldie’s Vineyard, which reaches down to the shores of Putaki Bay in the far lefthand corner, offers picnic baskets from its cellar door.

The boats moored in Putaki Bay are some ways out, as there’s a wide mudflat that gets exposed at low tides. Godwits come to feed here. Cockle beds are re-establishing themselves.

Ostend Wharf, some time between 1910 and 1919

On the eastern arm of the bay, the Sea Scouts den has some history. The hall and slipway were built in 1956, and the two big wooden cutters were built on the island (in Anzac Bay) some years before. Waiheke Sea Scouts flourished between 1960- 1976, after which the movement declined precipitously. In 2005 scout master Graham Crooks and his mate Ian Nicolson began the resuscitation. Waiheke Sea scouts is now thriving again with about 60 kids involved.

You need high tide to continue paddling up Okahuiti Creek. We enter Dead Boats Central. Or as some may put it, the realm of the picturesque. Sadly, shipwrecks have no place in our hardedged world: they are legally obliged to be removed and broken up. But with those scattered about the mudflats, I don’t think the owners (if they exist) are listening.

The causeway at the head of Okahuiti Bay was built in 1961. It was prompted by a recommendation from an ‘interdepartmental committee.’ Check out the interpretive panel by the sawn-off boat and you’ll see an aerial photo of the bay before the causeway. There was a sandy beach behind where the Sports Club is now, a temporary fishing camp for early Māori.

Okahuiti Causeway SportsPark League mascot

Waiheke as a home for sculpture also includes that of the folk-art kind. The dolphins sculpture pays deference to the Dolphins netball teams of the sports club. Just across the way, the ram honours the successful Rams rugby league team. After it was installed, the ram had its testicles removed by persons unknown. Twice. That’s why the replacements are now securely padlocked on.

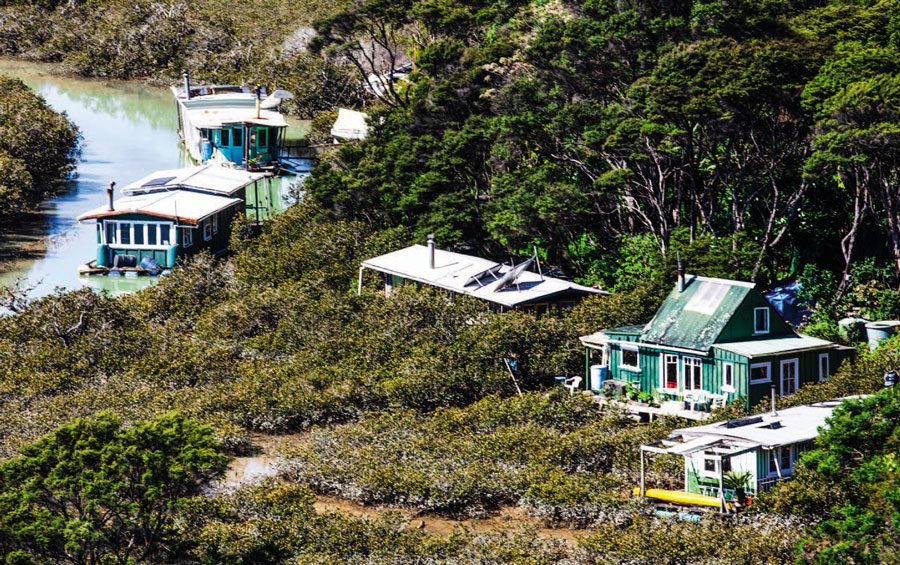

Paddling around the shore before the tide goes out, we’ll pass by the houseboats. Three of them are currently inhabited. A bloke I spoke to through a houseboat window said, “It’s just people looking for places to live; there’s nothing wrong with that. Our houseboats are perfectly legal.” But he added that “the Council periodically gets aggressive with us.”

Then we come to the headland that’s at the end of Wharf Road. Here’s where Ostend Wharf was built, 140m long, in the early 1900s. ALL YOU NEED IS LOVE is the island’s most famous and enduring piece of graffiti. It was first painted there on a wall by the slipway parking by Ollie, the son of late, great Waiheke artist Zinni Douglas, in the middle of the Beatles years.

Dave McCraken sculpture, Okako Bay

It’s one of five new marine reserves recommended in a 2016 report for the Waiheke Local Board by marine biologist Tim Haggitt. It would protect the rimurēhia, or sea grass (Zostera muelleri) meadows of Anzac Bay.

Hopefully with some water still under us, we enter the topknot, that bay above the bay – Anzac Bay. It dries out almost completely at low tide, except for a narrow channel that leads up towards the mangroves at Rangihuoa.

Then we come to the inlet where Taiwapareira Creek used to debouch into the sea. Where the skatepark is now was once the landfill site – back then environmentalists on the island warned of the dangers of having a leaching landfill so close to the sea.

Wiremu Hoete’s house at Okoka Bay, around 1842

The creek kinda disappears under the waste transfer station. Recently there were extensive works to build a subterranean outlet for floodwater from the creek since Auckland Council did not do a flood plan, as required by law, when it built the new resource centre…

The head of the Taiwapareira Inlet is another of Pūtiki Bay’s contested sites. The story here is of a shonky, dirtypolitics style takeover of a world-leading community project, by darker forces. In this case, the big guys were the bad guys – some of cartoonish dimensions – and it still hurts for Waiheke.

This is what happened: From 1998, Waiheke’s waste services were managed by a community company called Clean Stream, set up by the local Waste Resources Trust. It did good work. In 2009, the Auckland City Council’s city development committee voted to award the new waste contract (worth $22 million over 10 years) to Australianowned TransPacific International.

Rangihoua rooster

Waiheke Islanders weren’t pleased. Protesters marched to the Auckland Town Hall singing a specially-composed song Ko Tahi Tanga Waiheke (Waiheke speaking in one voice). Didn’t help. The Australian Corporation got the contract anyway. The waste management contract has now reverted to a community-based enterprise.

From here, we head up the mangrove-lined channel towards Rangihuoa, the prominent hill above the sports park, and a historic pā site. In the founding story of the Te Arawa iwi (based in the Rotorua area), they say they came from Hawa’iki, sailing a double-hulled ocean-voyaging canoe.

After a shark rescued the crew from being eaten by a huge sea creature, the people renamed their canoe – and themselves – Te Arawa, after that species of shark.

Causeway boat installation

Their landfall in New Zealand was Waiheke. They named what we call Gannet Rock, Horuhoru. Then they made their own way up Pūtiki Bay. They spent some time fixing their waka after the long sea voyage – Rangihuoa means ‘day of renewal,’ in this case meaning the re-lashing of the top gunwale boards of the waka.

On your way up the creek you’ll pass a collection of houseboats which have been there for at least 40 years. These folk have also had their tussles with bureaucracy, mostly about what happens to effluent from the houseboats. In the end, consent was granted for seven houseboats to be allowed in the creek.

A very high tide will take you and your kayak up, under the road bridge and the horse/walking bridge next to it, to the point where the saltwater reaches furthest inland. This is the spot where Waiheke’s roosters congregate. The rooster has become a symbol of Waiheke’s independence from the strictures of Auckland Council’s regular town planning. It all started when an old fulla in Blackpool who had owned chooks for years, got a complaint laid against his rooster, which awoke his new-from-town neighbours at hours not of their choosing. When City Council wallahs came to capture the rooster, he went bush and evaded them.

Putaki Oyster Farm

As we return back towards the mouth of Pūtiki Bay, on the left we come to Okoka Bay, aka Dead Dog Bay. About 40 years ago, local sculptor Denis O’Conner was kayaking here with his son Shaun and they found a dog, unfortunately deceased. Denis started calling it Dead Dog Bay, and somehow the name stuck. Even the adjacent sculpture park has adopted the name.

In the 1840s, Okoka Bay was the site of the kianga (settlement) of Ngāti Paoa rangatira Wiremu Hoete and his wife Hera. They built a distinctive round house in 1837, which included a spare room for guests, one of whom was Bishop Selwyn who visited in July 1842. Previously, Hoete had been held as a captive slave of Ngāpuhi in the Bay of islands, but was released in 1834.

Hoete made his way as best he could in the messy period of increasing land sales by Māori to Pākehā settlers. In April 1841, he was involved in the sale of 30,000 acres (12,141ha) on the Mahurangi coast to missionary William Fairburn for £200 in cash and over £200 worth of goods and livestock.

Rangihoua houseboats

For all his contrbution to land sales, Hoete himself became a victim of unscrupulous land dispossession. In 1845, one Adam Chisholm bought out the land at Okoka Bay, from someone who claimed to have ‘owned’ it. Eight hundred and fifty acres for two horses, other goods, and £2 cash. When Wiremu Hoete objected, Chisholm physically threatened the Ngāti Paoa chief on Auckland’s Queen Street. He successfully pushed through the sale through the counter-claimant, Pita Taurua of Patukirikiri. Hoete was forced to re-locate to land in Blackpool.

A land sale between Hoete and Charles de Witte, the Belgian consul to New Zealand, did go ahead – sort of – in 1844. De Witte purchased 500 acres on the down payment of £4 to be followed by £40 plus £6 for a house.

A homestead for the de Wittes was built in Wharetana Bay, the next dent in the shoreline to the south west. His response to the 1845 potato blight in Belgium was to propose the resettlement of 200,000(!) Belgians to Waiheke.

Alex paddles up the creek.

In October 2012 Wharetana Bay was again at the centre of contested visions of development. Auckland Council gave consent to place buildings almost at the water’s edge, well within the set-back limit. Waiheke locals didn’t like the idea, and protested by trying to block the arrival of a barge carrying two buildings. The protestors were there from 3:30am, and they slipped past a temporary fence that had been put up, to stand waist-deep in the water. Drumming and waiata provided the soundtrack. A dozen security guards were waiting with police. Seven of the protestors were arrested. Jacinda Ardern, then a Labour MP representing Waiheke and Central Auckland, was among those shouting the odds. The building was installed.

Next along the shore is Oakura Bay, which is joined to twin islands known locally as ‘The Sisters’ by a delicate, curving sandbar that is just above the water at low tide. The sandbar cuts across the northern entrance to Te Whau Bay, but can be crossed in a small boat at high tide.

I remember once talking to an elderly retired farmer from Scotland, while standing on the high point above Oakura Bay. A true man of the land, humble, soft-spoken, and with a sense of humour preserved, intact. In the end, when we shook hands at the ferry, Sandy said his day on the island had been 100%, and that saying this was a rare compliment from him.

Houseboats in Pūtiki Bay.

I wrote then that what the island had done for us, what it does for us every day, is in itself a rare compliment too. Just like a wee voyage around Pūtiki Bay can furnish us with so much a richness of stories. BNZ