An edited extract from Mark Sedon’s self-published book What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

I was halfway down a 40-degree ski descent, occasionally gazing out over the deep-blue ocean where icebergs were floating, seals were sleeping on the beach, penguins were walking about the snow on the shore and our 20m yacht was anchored in the bay. I smiled to myself. I had returned to the Antarctic Peninsula for my second expedition and this one suited me perfectly – we were just here to ski.

It was then that I started a small avalanche, which a member of our group skied into before being pushed down the slope towards the cold ocean and out of sight around the corner.

“Stop!” I yelled to the others above as I took stock of what had happened…

I was on my second trip to Antarctica, aboard the 20m Santa Maria Australis. We set sail from Ushuaia and after four full days at sea we spotted land – magnificent glacier-covered mountains cascading into the sea, rich deep-blue ocean, the odd fur seal popping its curious head up, schools of penguins, humpback whales and, most importantly this time, exciting-looking ski slopes.

The skiing in Antarctica is always a challenge. Picking out ice-cliffs and crevasses is especially challenging in bad visibility, so being out front I had to take care skiing first as we picked our way down the nice corn ski runs, making as many turns as possible. We hadn’t come here to sit about, so we would usually try and ski in all sorts of weather. But as the cloud continued to grow denser during our first day’s skiing, we decided to carry on back to the yacht, happy to have enjoyed some great turns.

Trying to find the right words to explain the allure Antarctica holds over me, and anyone I take there, is difficult. It’s a package deal. It’s not just the skiing, it’s the remoteness, it’s the wildlife, the mountains, the ocean, the grandeur of it – it’s as if you are in a giant Cinemax movie. Everywhere you look is spellbinding.

The danger is another allure, although guides go to great lengths to minimise it. The crevasses are huge and if you fell into one it might well be fatal. If you twist or break your leg, rescue is extremely difficult and may be impossible. We always ski with extra caution. You know in the back of your mind that if you blow this and break your leg it might well take the yacht a week to get back to Argentina.

As the weather was wet the following day, we headed south through the Lemaire Channel, also known as Kodak Alley because of its steep-sided mountains. They plummet almost vertically into the 100m-wide passage, which is clogged with icebergs and sunbathing seals. The rain had eased by the time we’d tied up at Hovgaard Island, so we went to a nearby penguin rookery and took a few hundred photos of the cute but extremely foul-smelling little critters.

The next day was clear, but a strong southerly wind was blowing and cloud surrounded the summit of Mt Demaria, which we intended to ski. Nevertheless, it wasn’t enough to deter our group and we headed over to give it a crack. The one seal we disturbed on the beach looked confused and curious as we unloaded our skis and three-day rescue cache (in case the weather changed and blew up a swell or pushed in brash ice that stopped us getting back to the yacht).

Off we went in improving weather, up the steep, soft snow. It was hard work breaking trail and hot in the Antarctic sun. We were also in the runout of avalanches from above, so for the first two hours we didn’t stop, climbing high up above the icebergs floating lazily in Waddington Bay to a shoulder 150m from the cloud-covered summit. What to do? Up or down?

Up of course! Because it was too steep for a skin track, we attached our skis to our packs and plugged steps up through a rock band and more soft snow to the lovely corniced summit just as the cloud cleared. What a view! We could see the nearby Lemaire Channel with perfect reflections of peaks in its deep blue waters, giant icebergs sunbathing silently in the bay below with occasional seals sleeping on them, and inland to the high peaks and the spine of the Antarctic Peninsula with its perfect untouched white ridges, valleys and peaks.

You’d have to call the skiing variable: some good corn, some way too soft. Corn snow is an enjoyable form of skiing. It starts the day frozen ice and ends up as slush. The time in between these two forms is called corn, a very easy and enjoyable type of snow to ski on. But we weren’t just there for the turns, it was a smorgasbord of views and sensations.

We were close to the bottom when I set off an avalanche that headed towards Nat. Once everyone had stopped, I skied around the corner to see where he’d ended up and found him tucked safely under a rock. No big epic, that was to come later while we were sailing home.

Soon enough it was time to head back across the Drake. As the German skipper Jochen wanted to beat a storm forecast for Cape Horn in five days’ time, we took off at full speed and for the first 24 hours everything went well.

Then at 1:00am on Day Two we had to shut down one of the two engines when the water pump broke. It was unfixable. Back to sleep – it wasn’t too much of an issue and we hoped to still beat the storm.

Then at 3:00am I awoke to yelling. When I turned on my light, I was horrified to see that the yacht was filled with smoke. Fire! I threw on my clothes and rushed upstairs to see Nick monitoring the diesel fire which had blown out. No fire thankfully — just smoke.

But then when we looked on deck the skipper and the first mate were holding on for dear life to the end of the mast’s steel forward stay with the jib sail pulling roughly on it. It had broken off the deck and was swinging wildly like an angry serpent. The heavy rigging was easily capable of killing someone or smashing the boat if it worked its way free. Victor and I tied into our lifejackets and went to help. They had managed to tie the jib off temporarily, but the sail was still pulling roughly against it. Being out on the deck at night, in the Southern Ocean, in ginormous 15-20m-high rolling swells with a strong wind was extremely intimidating. It took the skipper several dangerous trips up the mast before he managed to retrieve the sail by swinging out and sliding down it with a large sharp knife, cutting the sail away from the steel rigging.

The yacht tipped aggressively to starboard as the swell hit us beam-on and while we pitched steeply over there was enough light to see the dark black ocean as it appeared to be pouring off the sides of the Earth and into the darkness. I held onto the mast, also tied in, but the view didn’t actually terrify me, it more intrigued me. I was afraid for Jochen because when we lifted him aloft, the moving yacht would throw him into the mast and I’m sure he took quite a beating. It would have been so easy for a loose steel shackle or a sail end to hit someone in the face or head and do some real damage.

That took almost four hours and then the sun started to rise, revealing the major structural support of the mast gone. We were now down to just the one motor, at half speed. By then we were heading directly into the storm.

“What could possibly go wrong?” I asked Victor quietly.

We made a bee-line for Cape Horn, no one speaking aloud about what we’d do if the last engine broke down. We weren’t going to sink, but we might have floated extremely uncomfortably around the Southern Ocean for a week until the Argentine or Chilean navy came to rescue us. The group’s laughter became more forced, and we all sat around much more quietly, waiting for what Cape Horn, with its 800 sunken ships and 10,000 dead seamen, would throw at us.

But thankfully the storm weakened, and the engine worked tirelessly. After three more tense days, we passed Cape Horn in calm, smooth seas accompanied by a large school of dolphins. All of us breathed quiet sighs of relief, followed by celebratory drinks.

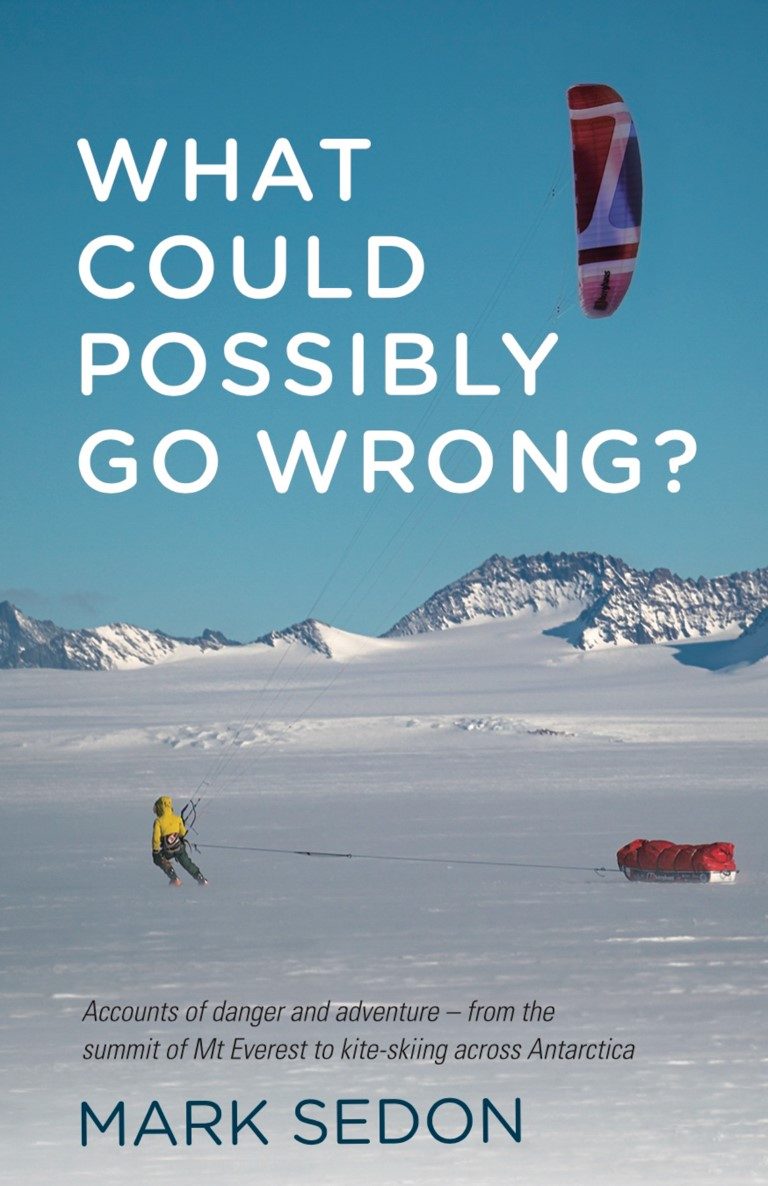

What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

A fatal helicopter crash – Summiting Mt Everest – Kiteskiing across Antarctica – swept by an avalanche into a deep crevasse – Trapped and starving in a Papuan mine – A broken mast in the Southern Ocean. This list of near-death experiences is longer than he’d expected . . .

Mark Sedon has experienced more highs, thrills, danger and accidents than most of us. The dangers have been life-threatening, the rewards often sublime and lifechanging.

This book is both an absorbing read and a challenge to every one of us to live life to the full and take risks within reason.

Although we don’t have to ski off the top of a mountain like Mark Sedon!

Books available from: www.whatcouldpossiblygowrong.nz