Scientists are baffled by a sudden, dramatic acceleration in the shift of the earth’s magnetic poles. They’re fearful not only of its impact on global navigation systems, but also for the entire planet’s well-being.

Every navigator knows that True North is different from Magnetic North. While the earth’s True North Pole lies atop the Arctic ice cap and is the axis around which the planet spins – a boat’s compass actually points to a point somewhere in the frozen wastes of the Canadian Arctic – about 500km away. The difference between True and Magnetic North is called variation and was first discovered by British explorer James Clark Ross in 1831.

The amount of variation differs across the planet. It’s roughly 20o around New Zealand but can be twice that in higher latitudes. Furthermore, Magnetic North is erratic and wanders constantly, changing very slightly every year. The annual rate of variation change is reflected on a navigation chart’s compass rose and needs to be factored into your course calculations. All very ho-hum.

But from the beginning of the 21st century (19 years ago) Pole ‘drift’ has been creating unease among those monitoring these things. Researchers have discovered that the pace of change in Magnetic North has accelerated significantly – it’s ‘skittering’ away from Canada, across the Pole, and heading towards Siberia.

“It’s moving at about 50 kilometres a year,” says Ciaran Beggan, a member of the British Geological Survey. “It didn’t move much between 1900 and 1980 but it’s really accelerated in the past 40 years.” The issue, he adds, is so severe that researchers are scrambling to update the widely-used World Magnetic Model (WMM) of Earth’s magnetic field, and thereby maintain the accuracy of global navigation systems.

The WMM reflects differences between Magnetic and True North and underpins all modern navigation systems used by ships and airplanes as well as land-based applications – drilling and mining, for example.

It’s maintained and updated every five years by the USA’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the British Geological Survey. Their latest update (in 2015) and was supposed to last until 2020. But because of the magnetic field is changing so rapidly, they want to update the model now to maintain navigational accuracy – an interim fix.

This repair job was scheduled for mid-January, but with the US Government’s shutdown (caused by President Trump’s impasse around the Mexican wall), NOAA staff are ‘on leave’. For now, everything’s in limbo.

WHAT’S CAUSING THE SHIFT?

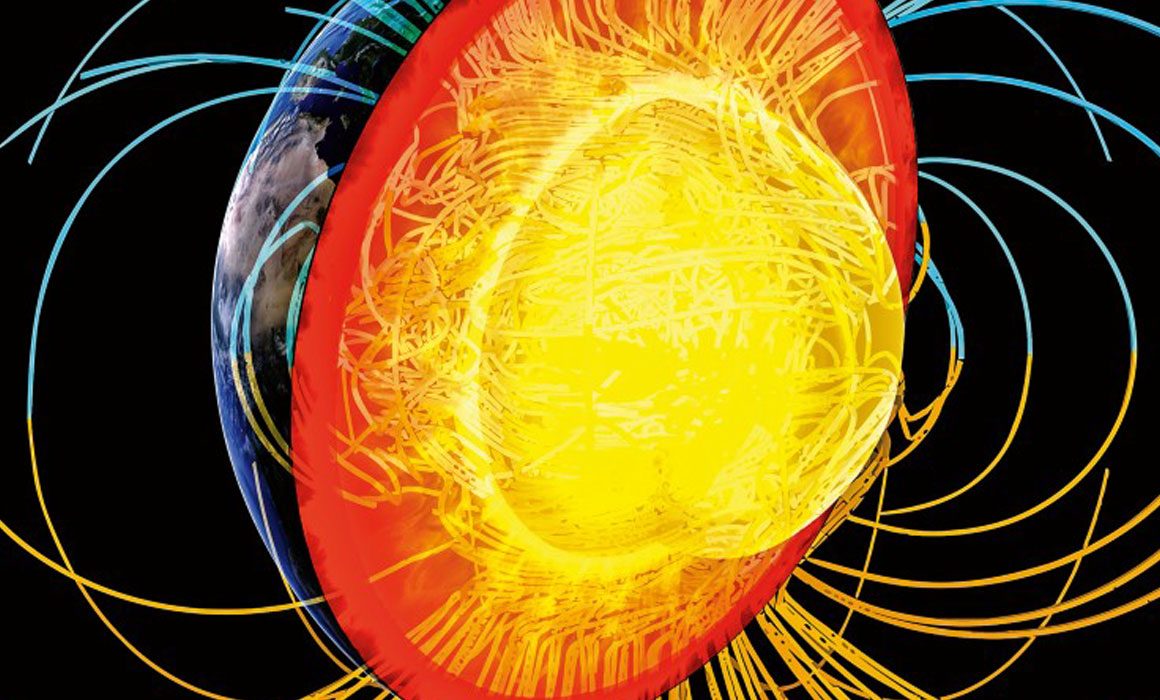

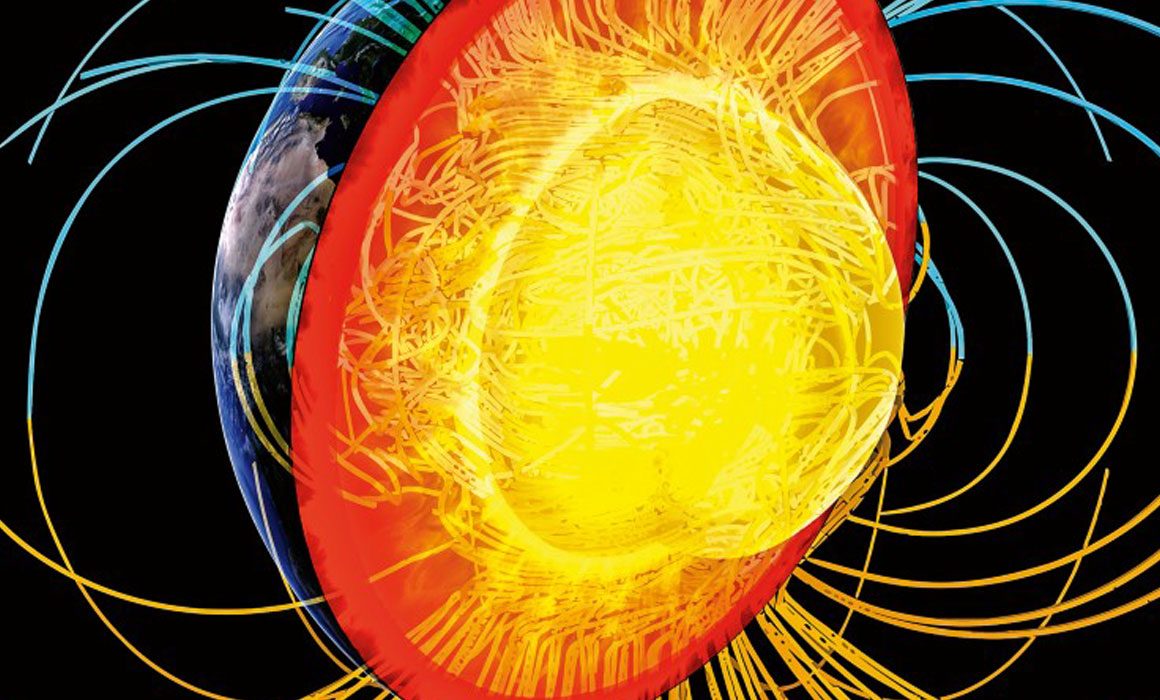

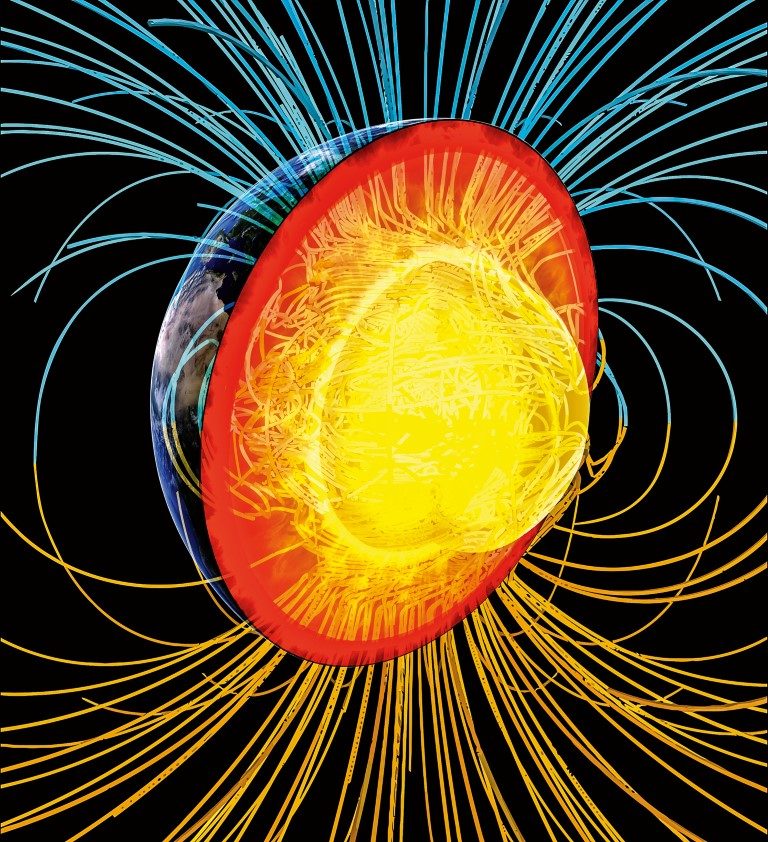

No one’s sure. Earth’s magnetic field has always been in a state of flux. It’s generated by the swirling movement of the liquid-iron core. As it ‘swooshes’ around, so the magnetic field changes. Some believe it has something to do with a highspeed jet of liquid iron underneath Canada. But explaining the sudden hyper-activity has stumped scientists.

The higher levels of activity have also renewed fears about the imminent possibility of a total magnetic pole reversal for Earth. In recent years scientists have predicted that Earth’s magnetic field could be gearing up to ‘flip’ – where the magnetic South and North Pole swap.

Scientists estimate the North and South magnetic poles flip every 200,000-300,000 years. But it’s been nearly 800,000 years since the last event – maybe it’s overdue? A Pole swap, say the gurus, would be catastrophic, wreaking havoc on satellites, power grids, ocean currents and animal migration, and would leave all life exposed to deadly levels of solar radiation.

Currently, the Earth’s magnetic field protects us from the most harmful portions of the sun’s radiation.

Not sure there’s much we can do – but if you are planning a voyage around the Arctic anytime soon, don’t trust your compass.