For Kinsa Hays a random phone call rekindles memories of a boat – and a life well-lived – from many years ago.

“Did you ever own a yacht called Teal?” the caller asked me over the phone.

Fifty years ago, we did! It was like contact from the grave. “Yes.”

“I’m Tony Stevenson. I’ve been doing some detective work to find previous owners of Teal.”

“You’ve found one,” I said. “My first husband Fred Herbert and I owned her from about 1965 to 1970, but Fred now has dementia.”

“I’m sorry to hear that.”

I was curious. “Why did you ring?”

“We rescued Teal from the wrecker’s yard,” Tony said. “I paid one dollar for her, and we’ve refurbished her. She’s like a new boat.”

I sat down.

“She’d been up on the hard for years. Nobody had touched her. She owed a lot of yard fees and wasn’t registered. The Tino Rawa Trust, of which I’m a trustee, paid the fees and for the refurbishment.”

“Crikey!”

“I’m offering you the opportunity to visit her. She’s being used as a classic yacht for training youth in sailing. She’s winning races in her class on Auckland Harbour now.”

“Wow!”

Next time I was in Auckland I tracked down the man whose name I’d forgotten, but Tony Stevenson was overseas. Instead, I found links to Teal on three websites: Tino Rawa Trust, Classic Yacht Association and Yachting Developments. They informed me that Teal was designed and built by the Lidgard brothers in 1946 for Willian Goodfellow and L.H. Clarke and was launched on 22nd December 1948 on Kawau Island. What a Christmas present! Later owners included Sir Keith Park, Mark Williams, T.L. Elliott – and now Fred Herbert can be added.

Teal was shorter, wider and her keel was not as deep as Fred and I had assumed. What’s more, she is registered as B6 whereas the photo in front of me declares she was B5. What had happened to our beloved Teal?

Restoration

In 2012, days before she was to be scrapped, Teal was rescued by the Tino Rawa Trust and put in storage until 2016. She arrived at the Yachting Developments boatyard in Hobsonville in poor condition, essentially a hull with not even a deck.

Her overall length is 38ft 6” (11.73m), beam 8ft (2.43m) and draught 5ft (1.52m). She’s a single-skinned kauri carvel construction and was restored and glassed in 2018. Her engine is a 20hp Volvo and rig is Bermudan – main, two jibs and a gennaker.

Fitted out in the style of a gentleman’s cruiser, Teal was lovingly restored over the course of more than a year, returning her to former glory. Says Stevenson: “Her new design acknowledges the past, but she has been reborn for the future.”

Her new deck layout and cabin design were the work of a team from Yachting Developments and members of the Tino Rawa Trust. All previous modifications were stripped away. I thought of all the time and love that we’d spent maintaining Teal on the hard over the years. All gone to make way for the new.

The brief had been a design that allowed for short-handed sailing, so Teal would be more of a day-sailer when completed. The team created a new cockpit and cuddy cabin set-up in keeping with Teal’s character. The large cockpit will allow for bigger groups of youth sailors, the cuddy cabin providing shelter in inclement weather.

Getting to know Teal

Gentleman’s cruiser she might well have been, but for us Herberts Teal was a family cruiser, beginning with ourselves as young marrieds. We had adventures – memorable, relaxing and downright frightening.

Our first time out we spent New Year’s Eve stuck on a sandbank in the Panmure River. Coming into the Bay of Islands, we got mixed up as we changed from a small-scale to a large-scale chart. We found ourselves on a ‘foul shore’ and, not knowing where to anchor, spent the night sailing between Cape Brett and the Ninepins under jury rig, towing a rope anchor to slow us down.

When the weather became blustery, we had to start the engine each time we went about. Sharks swam around us illuminated by phosphorescence. I was petrified and could only take the tiller for a brief period. Fred took over for most of the night. We watched, close up, the dawn carnage of birds, predators and small fish at Cape Brett. It almost made up for it.

We headed to Deepwater Cove, but were twice unsuccessful at anchoring, dragging on to other boats as we tried to sleep. Someone handed us fish for breakfast and we gave up on sleep.

I remember going ashore, finding a cold stream and sitting in it to keep awake.

On another trip, we anchored at Urquharts Bay at the entrance to Whangarei Harbour, with the Marsden Point oil refinery lit up like Fairyland. During the night the wind changed and we had to move. Teal’s engine wasn’t powerful enough and we only had a pathetic masthead light.

We moved into the shipping channel to find a better anchorage upstream. The ebbing tide was running at speed – too fast for us to cut across it. A heavy-duty shipping buoy loomed ahead. In horror we watched as we closed in, sweeping past it with inches to spare! I don’t even like to write about it.

We took Teal to the bottom end of Waiheke, Te Kouma, Whitianga, Whangaroa and Great Barrier Island. At Kawau Island we sailed up Bon Accord Harbour and went ashore to the place where Teal had been built. We met Dave who became our sailing companion in his 28-foot yacht Tiara, always painted green with a matching dinghy.

Dave had one deplorable habit: when we met up, say, at Otehei Bay, he’d bring out a crate of beer and take the tops off every bottle. No one was allowed to leave until they’d been finished. Once he’d been chilling a bottle of wine for me in a bucket let down into the sea. He hadn’t tied the rope well and it slipped off. Far too deep for us to reach.

Another time we sailed with Dave up to Whangaroa where Fred’s grandparents had lived. We anchored at Kingfish Point and went ashore to the Lodge, as you do, for a beer. By the time we wanted to return to our boats, the tide had receded – taking our dinghies with it. Bad start to a holiday. Somehow we got ourselves back aboard, and early next morning motored into all of Whangaroa’s inlets – of which there are many. No dinghies.

We headed out to the open sea and spotted a sand barge coming in. Through binoculars we saw it was towing a green dinghy on one end of its square stern. Dave’s! Our hearts sank. Then as the barge came closer, we saw the white dinghy on the other end of the stern. Ours! We followed them into the wharf and bought our rescuers a crate of beer at the hotel.

Children

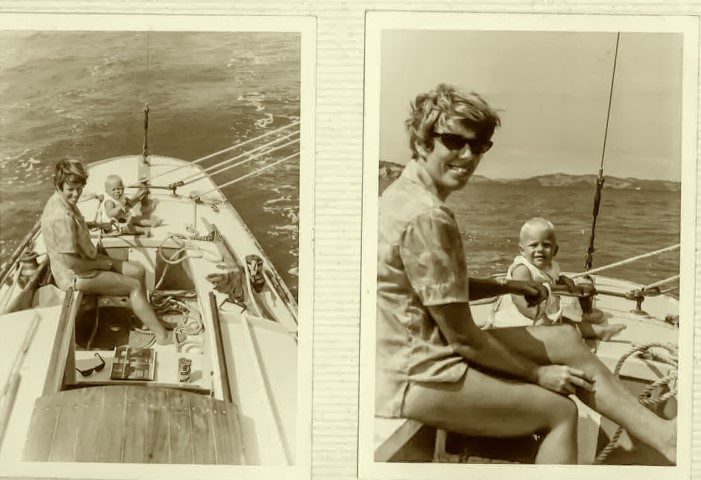

There was a gap in holidays, then we added a toddler. Jeffrey never fell overboard despite the lack of safety rails and Teal’s narrow beam. Because he was too small for a life jacket, we tied a rope around him and attached it to the mast. We put him in a swing seat slung over the boom and later, left him in the dinghy by himself, where he probably played pirate games while we listened for any splashes. None. And we rowed ashore daily to give him more freedom and ourselves some relief.

Later still, with more confidence than sense, we added a three-month old baby who slept in a carry cot at the foot of the mast. These were the days before disposable nappies and we had to adapt to the lack of facilities. We tied the nappies firmly on a rope and dragged them behind us to clean them, going ashore to find a stream in the evening to rinse them in.

Fred also strung a rope between the rigging to hang the nappies up overnight. This Chinese laundry effect was definitely non-nautical. I had just enough breast milk to feed Suzy at 4am without waking everyone, then made up formula on the two-burner primus on gimbals for the remainder of her feeds.

Teal was a major part of our lives for many years. We had to sell her when we went to Sydney to live for a while.

Thank you, Tony Stevenson and the Tino Rawa Trust, for rescuing and re-purposing this classic yacht. She deserves it.