The lights are back on, marking the channel into Ngunguru in Northland. We were going to sail up to this creek to fetch our Ukrainian shipmates Sergei and Tonya, but the river mouth looked blocked by a sandbar.

The local knowledge from their daughter Olya, who lives there with her Aussie partner Dave, confirmed it. For it turns out Olya and Dave’s favourite surfing spot is the break on the bar at the harbour mouth. So not exactly perfect for incoming yachts, eh? Till now.

The sand appears to have shifted recently, opening up the channel somewhat. And Captain Percy, who all the locals said we should contact for further information ‘cause he knows everything about everything – well, he’s had the channel buoy lights switched on again. So, good to go. Sort of.

Thing is, I’d still consider it a tricky harbour entrance, especially with a south-easterly swell running, or wind against tide. It would be a passage to double-triple-check for safety for any skipper of a yacht not familiar with it.

But if you have a well-found, sea-capable powerboat and know the area and its tides, then fine. Indeed, when we were checking out the channel from the headland that separates it and Motutara Island from Whangaumu Bay, a few local fishers obliged by heading out to sea. Perfect timing for Lesley and her long lens.

The views from the headland are sublime. South across the bight of Ngunguru Bay to the Hen and Chickens Islands and Whangarei Heads; NE in the sparkling clear autumn sunlight to the Poor Knights Islands.

Arriving at the headland, I was making small talk with a couple standing there, looking friendly. I espoused my theory that the sum total of all the footsteps we take in life lead us to where we’re standing now. And to wind up here, means good decisions must have been taken along the way.

The couple immediately warmed to my idea and whipped out their cellphone cameras to show me they had been married in this same spot, just a week before. I think my theory landed well with them.

My mind turned to our Up the Creek adventure planned for the next day. The languid green ribbon of the Ngunguru River, mangrove-lined, and with hillsides covered in regenerating bush, was beckoning, along with the promise of tales of a rich history, and passionate, creative locals.

But the harbour passage was/is not for us. When we do-revisit on Skyborne our 12m Schionning sailing catamaran, for safety’s sake we’ll probably anchor in Kowharewa or Pacific Bays, the southern arms of the Tutukaka Inlet, and just over the hill from the Ngunguru entrance. Or rent a berth at Tutukaka Marina.

Trouble is we had already come up by road. Me on the bus from Auckland, Lesley following in the car with her camera and the inflatable rubber dinghy bundled up inside.

The orders from Captain Percy were brisk. Meet me at my landing, 11km up the creek, at 7: 30am to make best use of the tide. He used to run boat tours up and down the river, but the cost of compliance – and the durned Covid thing – had put paid to that. His boat was sold to the good folk at the Paeroa Maritime Museum. So, good thing we had the little inflatable, even if it was going to be a tight fit.

But our dawn watch wasn’t as sharp as could be. After blowing up the dinghy, a quick run to Tutukaka for more petrol, raising the not-morning-folk among us, and a hasty brekkie, we only launched the boat at one of the Ngunguru waterfront ramps at 7:30. By now the tide had begun to turn. We made it some way up the river, seeing interesting waterside homes, a tiny bach (or a huge maimai) on an island hardly bigger than it is, and mural artwork of inexplicable provenance: on some concrete foundations, the Eye of Sauron, a tree with rainbow foliage, and a wombat. Where they came from, or how they were connected, we could only guess. The flock of tōrea pango oystercatchers roosting nearby seemed un-fussed.

Then past the site of the historic hotel on a spit of land that is so almost an island.

There’s quite a story about that establishment, including the proprietors (different but related) absconding twice. And the place suffering three fires, the last one terminal in 1923.

Back in the day, the hotel serviced the many people involved in brisk trades up and down the river. This was before the road from Whangarei to Ngunguru was finally completed in the 1930s. Before that, the scows were doing what Kenwood trucks do today.

It’s little-known now, but this part of the country supported a few expansive coal mines. Where there’s now the (very) quiet little settlement of Kiripaka, there were once 600 miners living there. The coal was discovered here in 1892, and the first shipment sailed out (or rather, took the tide to the harbour mouth) that same year, under the command of Captain Shoebridge.

The two coal mines operated successfully for 29 years, and 630,000 tonnes of coal was exported, mainly to fire the hearths and furnaces of the growing city of Auckland. The two mines amalgamated in 1908. Kiripaka and the bigger mine in the Panapo Valley a bit further inland, both closed in 1921 – although Panapo was never worked out. The company found it more profitable to shift its operations to another mine near Hikurangi and send the coal down to Auckland via the newly laid railway.

In this heyday, it’s said that every Hauraki Gulf scow ever built sailed up this creek with and for a cargo of some sort. The river trade was two ways: upstream the scows carried general goods, machinery, meat and new settlers. Later, fertiliser (the land cleared of big trees and burned for paddock was only fertile for three years). Downstream, coal, fire clay (for making bricks, extracted from the river banks upstream – this went to the Crown Lynn factory in Auckland), kauri timber, passengers and travelling priests. There was a separate mail launch working too.

Many of the boats would have come to the mangrove inlet alongside what is now Old Mill Lane which leads to the site of the water-wheel-driven machinery set up in the valleys by James Busby and Gilbert Mair in 1843. More local say-so: This was probably the first fully mechanised timber mill in the southern hemisphere. A channel (still there, but overgrown) was cut from the Waitoi Stream to power the waterwheel. The detour from the main channel up Mill Creek – perfectly navigable by small boat – is a turn to starboard just after the historic Cape Horn Cemetery.

Scow Landing is where the road from Whangarei crosses the Ngunguru River. This wasn’t where the scows were loaded with coal – it’s a modern, council-applied name. The real Scow Landing was 1.6km downstream, just near Captain Percy’s Landing today.

That road bridge is about 12.5km from the marker posts at the entrance to the harbour channel. There’s a lovely picnic spot there, just off the main road up Waipoka Road – a great place to put in kayaks for further exploring. Just upstream the river takes a bend northwards, into forested hills, and home to kiwi. The farmland below the hills in this district is criss-crossed with 1,500km of drystone walls, some built as early as the 1860s by Dalmatian gum diggers out of that particular luck.

But we never got all this way upstream in our rubber dinghy. Our wee 2hp Honda would have got us there, no worries, but slowly against the outgoing tidal stream. Even slower when stopping for frequent photoshoots of interesting old boats, riverside properties, swimming dogs, and wildlife.

Only we got a phone call from Captain Percy. Other people had a need for his time too. Change of plan. We were to backtrack and meet him at the Tutukaka Marina, where he’d give us the gen.

We found him there cradling a real treasure: a book of historical photos and correspondence and ships’ plans, all to do with the Ngunguru River trade. Which he unstintingly shared with us. Some rare and unique historical photos you won’t find anywhere else, which Lesley was able to shoot, removed from the book and on the café table. My favourites were the two steam tugs, the Tui (under Captain Shoebridge) and the Lena (Captain Hansen) towing coal barges, and the line of 12 scows in the Ngunguru Estuary. And in every picture of the river, more interesting boats. We were transfixed for hours. Great yarns central.

But back to the river. Ah! The hotel. Wibbotson’s Ngunguru Hotel. Here’s (just part of) its story:

A sea captain, Thomas Stewart, bought the land from mana whenua sometime in the 1860s. It was recorded as the Tarata Block, and Captain Stewart became one of the earliest European settlers of Ngunguru.

Captain Stewart married Ann Mary, the daughter of a Ngāpuhi rangatira, and a notably beautiful young woman, but for reasons I can’t establish, exiled from the tribe.

Mary was unversed in English and reading and such stuff, so the good Captain Stewart hired an English teacher for her. Only he soon eloped with her.

The Captain was having none of this. He hired another man, a local good and true, named Peter Sturt-Brown to go find her and bring her back. Which he did – all the way from Australia.

Peter was able to persuade Mary to return. And she then settled down with Captain Stewart. But he died by drowning in 1867 aged only 49. Mary then promptly took up with Peter Sturt-Brown.

So Peter inherited the Tarata block in 1868 through marriage. And, energetic fulla, he built the Ngunguru Hotel on the water’s edge. He and Mary ran the hotel together. The jetty Peter built, Brown’s Point Jetty, lasted until 1917, was rebuilt after a storm, then rebuilt again after being nailed by another gale in 1922. This jetty served the hotel and Ngunguru settlers until 1932 when the road link to Ngunguru from Whangarei was finally built.

History then repeated. In 1892 Peter did the same Aussie runner with another local married woman.

Mary got even. She applied to the Court for a Petition to adjudicate him a Bankrupt on the grounds that Peter did wilfully desert her without reasonable cause. Unusually for the times, she was granted the property under The Married Woman’s Property Act, 1880.

When Mary sold the hotel (not the land) she gave the money to the Salvation Army. Perhaps she was making up for the many reports of the hotel being “a most wild and bawdy place.”

It’s quieter now in these parts. The sandspit that guards the estuary was once in danger of being developed into an upscale beach resort. The locals reckoned better not, and the Ngunguru Sandspit Protection Society (NSaPS) lobbied hard to get it put into public ownership. This happened in 2012 when the Government, via the Department of Conservation, swapped a parcel of surplus government land and buildings in Napier to gain the sandspit. A win-win for all, including the New Zealand dotterels, whimbrels, royal spoonbills, Caspian terns and other unusual birds that hang out there. Like the ruddy turnstones. No, I had not heard of them before, either.

Since then, the Ngunguru Sandspit Protection Society has campaigned further to get Whakairiora Mountain at the southern end, also an important natural habitat, into public ownership. They started a Givealittle crowdfunding effort to raise $1.6M of a $3.6 million asking price, with a secret philanthropist offering the top-up. But they didn’t win this time, and by the 28 February 2022 deadline, they returned the $107,380 they had raised to the donors.

Still, Ngunguru township itself remains down-home authentic, quite unlike the amped-up overseas visitors vibe of Tutukaka over the hill. For our Ngunguru Up the Creek adventure, I had the inexplicable yet earnest desire to be wearing a corny tourist T-shirt. But at the waterfront Bob’s Store there was no such thing. I got real by simply having a vanilla ice cream. A wee tub with a wooden spoon.

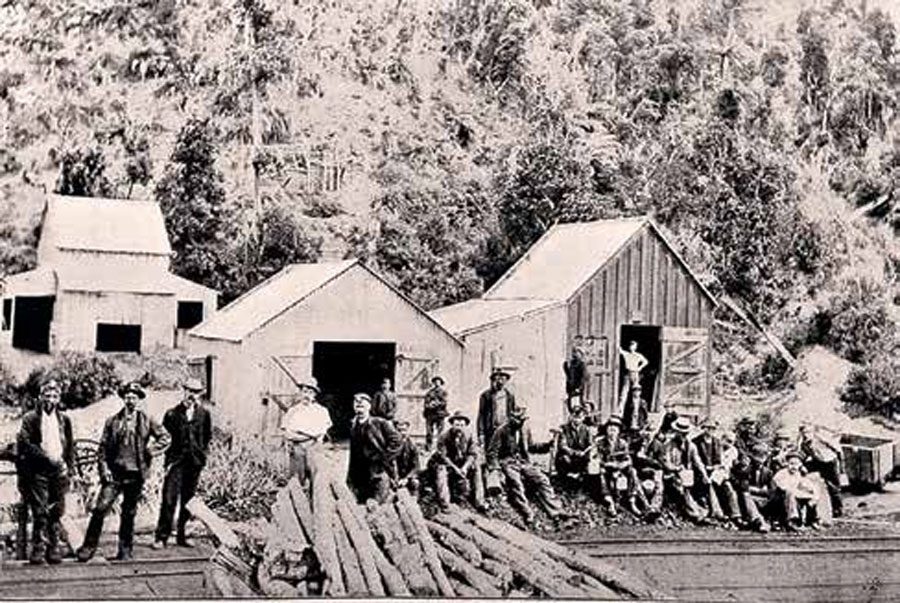

Just next to Bob’s Store is a little promontory (now the location of a few fine waterfront homes) that was the site of another early timber mill – see the pic with the bullock teams. This mill operated till 1914, when it burned down.

A little way along is the Ngunguru School, one of only a few in New Zealand to have absolute waterfront position. A tradition at the 150-year-old school is to ring the bells when dolphins enter the harbour. (This is fine, but the symbolism at a playground just nearby, of a sculpture depicting a whale diving straight into the dunny, eluded me…)

More history: the 100-ton schooner Southern Cross, the first of five eponymous ships owned by the Melanesian Missionary Society, was wrecked here in 1860, returning from the islands. No lives were lost.

Ngunguru has lost none of its enduring, natural appeal either. This is a boating Up the Creek adventure with more stories and lovely old boats than you can shake a stick at. And that, I say, is a very fine thing. BNZ