Both the journey and the destination have attractions for the cruising sailor, especially on Australia’s historic Moreton Bay, writes KEVIN GREEN.

The Moreton Bay region of about 800 square miles is a myriad of islands and swatchways where the cruising sailor could spend years exploring. Safely below the cyclone belt of the Tropic of Capricorn, so with year-round sailing, it’s been a good place to base our pocket cruiser for a year.

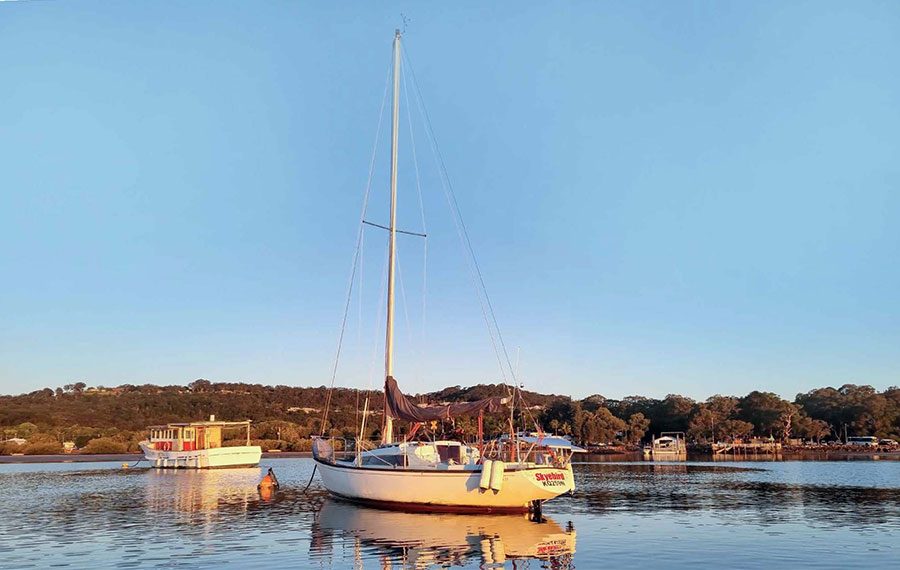

Our sailing plans for heading further north, beyond the Brisbane region after our departure from Sydney in 2021, were delayed by the La Niña weather. So, my wife Carole and I contented ourselves by leaving our 25-foot Contessa in the Gold Coast/Brisbane region, which was also handy for my project work there and a good base from which to explore the area.

Such as the many islands near Brisbane. These contain layers of indigenous people’s history, and they continue to live here despite the waves of colonial explorers (and latterly settlers) who now dominate the region.

British explorer Matthew Flinders stormed ashore here, followed by white convicts who were incarcerated among the islands. Transported here by sea, long before this Queensland region was connected to the settled south, there were plenty of remote islands to house them and others with diseases such as leprosy.

SPRING CRUISE

Sampling this region on our pocket cruiser, Skyebird, was our twoweek mission in October. This trip would take us to islands further north than the early voyage (see November issue’s Part Two). The earlier trip had been to some of the muddy islands, whereas this trip was to the sandy islands, so we looked forward to swimming and sunbathing. October is an ideal time for this region, because temperatures hover around 20-25°C and the water isn’t cold – and it’s well south of tropical Australia’s poisonous jellyfish.

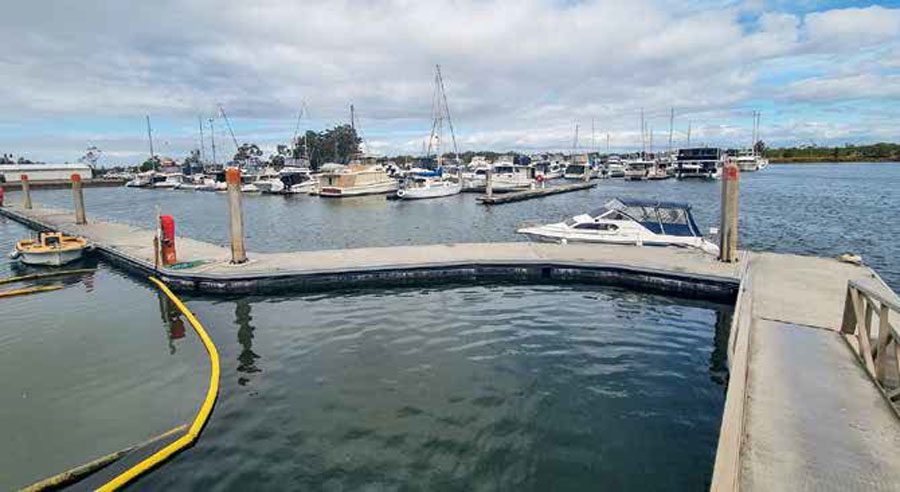

The voyage began with us hauling-up our anchor in the narrow channel near the village of Jacobs Well and motoring north with the flood tide towards these islands at the southern end of the vast Moreton Bay. The narrow channels make sailing challenging but running with the following wind we used a poled-out genoa. The village of Jacobs Well is beside one of the largest marinas on Australia’s east coast, Horizon Shores, where we’d berthed our yacht for a few months.

Moreton Bay is sheltered from the Pacific Ocean behind three long barrier islands – Moreton Island, North Stradbroke and South Stradbroke – creating a confined cruising ground that contains dozens of islands amid very shallow waters. This inside channel is a busy thoroughfare between the Gold Coast and the city of Brisbane, but avoiding the main channel in the myriad swatchways allows tranquil boating.

So, leaving the bustling south behind, our 8hp Mercury outboard buzzed contentedly in the cockpit well, pushing us along at four knots – plenty of time to enjoy the scenery. Such as the sugar mill at Rocky Point and a few miles inland, the rum distillery at Beenleigh. I’d visited them earlier, cycling through the canefields with their swaying stalks and flatlands that once were wild swamps where indigenous nomadic tribes hunted kangaroo and wallaby.

Later in the day, we motored off the main channel into a secluded pocket at the south end of Russell Island known as Brown’s Bay, where the anchor was dropped in about 3.5m of water. This would allow for the 2m fall of tide to keep us afloat at low water. Ashore, a rustle among the mangroves revealed the ochre wings of a Brahminy kite alighting, while chattering from the bow was the work of a family of swallows who’d taken up station to swoop on the insects skimming the muddy surface of the anchorage.

Decanting the shrinking ice from our cooler box into two glasses, we poured some copper-coloured Beenleigh rum to toast our first anchorage as we sat in the cockpit watching the sun sink beyond the foothills of the Great Dividing Range. It’s Australia’s largest chain of mountains and runs discontinuously all the way from the far north to the far south of the country’s east coast.

Shortly, the familiar meths aroma came from the stove as Carole heated some quick-cook rice to go with our stir-fried chicken. Skyebird is simply run, with two solar panels and three batteries, which meets all our needs.

RIDDLE OF THE SANDS

A persistent northerly wind required motoring – through the winding channels where tow barges slowly overtook us and faster ferries skimmed past on their way to the populated islands of Russell, Macleay and Lamb.

For our voyage, we were going north, beyond these islands we’d visited previously. So, with the bustling mainland to our west and the islands to our east we continued north, at one stage taking a shortcut across a shallowing sandbank on the ebb tide.

Around us, the views of muddy banks gradually changed to sand, until passing a narrow gap between the mainland and a gorgeous yellow beach, we anchored at Coochiemudlo Island. Or tried to. The ever-present strong currents in this region dislodged our Danforth anchor from the sandy bottom, sweeping us among the mooring field until I grabbed hold of an anchored yacht. Extricating ourselves from our anchor warp that had jammed under the keel took some cursing and pulling before we eventually reset the anchor and rowed ashore.

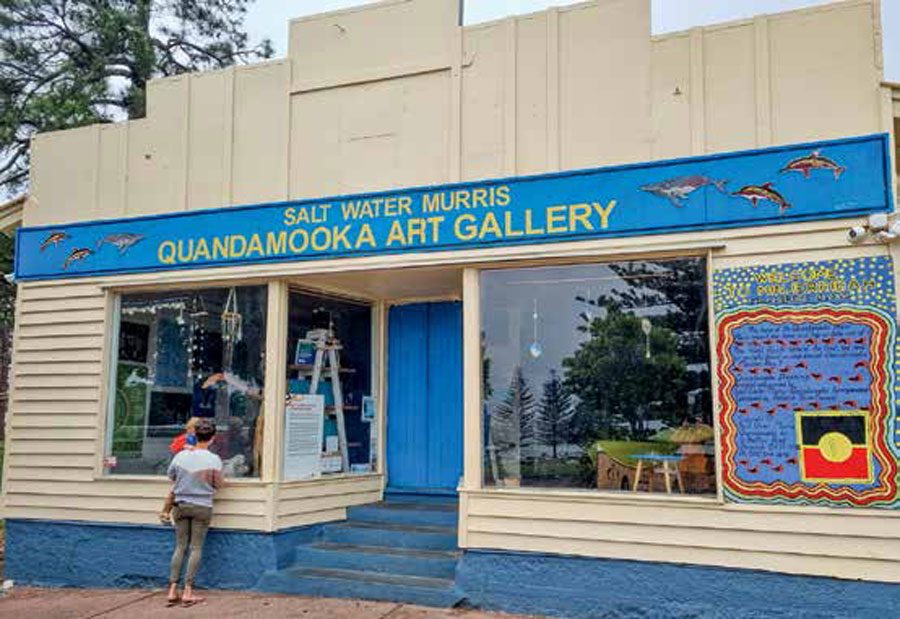

Perhaps the most touristy island in the region, Coochiemudlo is nevertheless quaint. Named by the Quandamooka people for its red ochre (probably used for adornment before ceremonial hunts for dugong), nowadays the island is known for its holiday homes. And the landing place of British explorer Matthew Flinders in 1799, the first known European to arrive.

After an hour’s walk we had circumnavigated it and retired to its friendly Stone Curlew Cafe for a tasty burger with chips; while we watched the throng of elderly residents and younger holidaymakers pass by.

A few days later a favourable tide swept us out to the vast open expanses of the main part of Moreton Bay. Its openness meant coastal sailing rules applied. So, diligent checking of the tides and forecast especially, as any north- or south-facing anchorages are exposed to a long wave fetch.

One of the most notorious anchorages for this weather was our destination, the south-facing Horseshoe Bay on Peel Island. Gliding over its azure waters, and welcomed by the piping of an oystercatcher, brought us to a place of blissful tranquility. Unlike the heavily-populated Coochiemudlo, Peel has no residents and apart from the dozen yachts spread out along its mile-long beach, there was nothing but nature.

Its shallow-inclined beach required anchoring nearly a mile from shore, so we fastened the 2.3hp Honda outboard to the transom of our rubber dinghy for the run ashore. My plan was to take the trail to the old leprosy hospital, but a private sign prevented us, so we swung east, along the Telegraph Track, with its bare poles as markers. Half an hour later we emerged at a cove with a wreck of a steam barge – our Navionics chart noted it as the Platypus.

It sat at the pierhead with only its boiler showing between its protruding transom and bow. A timely reminder of what a southerly buster wind could do to anchored shipping. Climbing the hill above brought us to the barred windows of an old isolation ward. We paused to consider the poor souls incarcerated here under its tin roof, amid the heat and insects.

Afterwards, back at the beached dinghy, we swam in the crystal-clear waters and lounged on the empty sands – entirely alone apart from a family on a trailer-sailer who had been camped here for a week at the far end. The following day a southerly forecast sent the trailer-sailer and us scurrying away. Hoisting the genoa we glided from the anchorage with the compass needle again pointing north.

MINJERRIBA

In the far distance the towering dunes of the anchorage known as Sandhills shone in the morning sunshine on Moreton Island, the second-largest island in this region and one of the three largest sand islands in the world, along with Fraser Island 100 miles to the north. To the south lay the largest island in the region and second largest sand island in the world, North Stradbroke (or Minjerriba as First Nations called it), which was our destination.

With a southerly blow coming, there would be no shelter along the west coast of Moreton Island and the Sandhills anchorage, so we followed the snaking channel into the town of Dunwich. Known as the One Mile the anchorage is full of moorings, so we grabbed one temporarily until we decided our next move.

We’d come to visit the famous Little Ship Club and shop at the Spar for supplies. After a friendly word ashore with club member Brett, we were given permission to use the vacant mooring for a few nights. Our plan had been to briefly call here then move just north to the anchorage of Myora that was sheltered for both northerlies and southerlies.

The Little Ship Club staff made us most welcome after we signed their visitor’s book and we lounged with ice-cold ‘Gold XXXX’ beers on the lawn overlooking the entirety of northern Moreton Bay, which we voted the most scenic club after the bowling club on Macleay Island.

NATIVE TITLE

The walk into town took us through the cemetery where we paid our respects to the lines of identical crosses marking the 44 passengers of the sailing ship Emigrant who died from typhus in 1850.

Harking back to the days when the port was a quarantine station and asylum, the Emigrant had docked here. Pictures in the town’s museum showed neat rows of buildings cascading down the slopes – the medical wards. Some were repurposed to become shops and a few remain, including one housing the fascinating museum.

A weaving workshop was being held in the museum during our visit and my wife remarked with surprise that it was a Caucasian instructor teaching the First Nations women. Back in the day, Aboriginals weren’t allowed in town but were kept on the island as indentured labour for the hospital and paid in rations; camping at the freshwater springs at nearby Myora.

Thankfully, a more enlightened view and some tough lobbying by their ancestors won a major land-rights case here in 2011 and today most of the bush-clad island is managed by the Quandamooka.

One of the lobbyists for this Native Title claim was Uncle Ian Delaney, a Quandamooka elder and former commissioner at the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission. Meeting him at the Sports Club, we chatted about the settlement’s history.

“Many of our people were massacred, some of their bones are to be found under the foundations of the surf club,” said Ian. The surf club is in the island’s major tourist resort at The Point which has several hotels and units for holidaymakers. It also has some of the best beaches I’ve seen in all of Australia, which is saying something.

“I’ve just been to Moreton with some of our mob to remember the old ways,” Ian told me. Regaining pride in their culture and retaining their languages was all part of what he’d been trying to do since the 1970s. Along the streets and in the Sports Club, talking with both white and black locals was interesting.

“Without our mining and the money put back into the community, there would be nothing here,” said retired mine engineer Len. Sand-mining by foreign companies had scarred large parts of this bush-covered island and pollution from their workings is a long-term legacy.

Now, tourism pressures are building with, reputedly, a higher visitor density here than even the Great Barrier Reef because of its proximity to the major city of Brisbane. While ambling along the boardwalk around The Point we came across a tented encampment which First Nations people had erected to prevent the building of a whale watching platform and museum.

Back in the One Mile, a few days here allowed us to get to know some of the liveaboards. But a shop assistant told us that Redland Council had plans to clear them out, so that more tourist boats could use the small anchorage. Sailing off to return south, we watched from our cockpit as the car ferries crossed our bows bringing dozens of 4WD cars and hundreds of visitors to experience sand driving and beachside partying. Such is the dichotomy of how we Australians, in so many different ways, enjoy and explore this amazing continent. BNZ