Aquaculture is often touted as the future of seafood, but is it really?

Scrolling through Facebook the other day, I stumbled across a discussion on the relative merits of wild-caught versus farmed seafood.

It was prompted by someone reporting they’d enjoyed a meal of basa – a farmed freshwater fish imported from Asia. Sold frozen or freshly thawed, basa – a type of river catfish – costs considerably less than wild-caught marine fish.

That anyone would eat basa elicited howls of derision from some members of the group – for a variety of reasons: it was imported from Asia; it was a freshwater fish; it was cheap; it was frozen, but most of all because it was farmed, not wild. “The only fish worth eating is fish you catch yourself,” they cried, with some stating they never buy fish. But most people are unable or uninterested in catching their own fish, just as most people don’t hunt their own meat. They buy it.

And global demand for seafood is growing, even though wild fish populations are in free-fall. With the total commercial catch shrinking, aquaculture is filling the gap in supply, which on the face of it would seem to be a good thing. But is it? Many people don’t think so.

There are many good reasons to be unhappy about industrial- scale commercial fishing, but what exactly is the beef people have with aquaculture? We know the current global consumption of wild seafood is unsustainable, so meeting future demand from wild stocks will be impossible. If we want to continue eating fish, it seems aquaculture is the logical way forward.

Aquaculture is booming: salmon in Norway, Scotland, Chile, New Zealand and Australia; carp in central and Eastern Europe; catfish, carp and other freshwater species in China and southeast Asia; rainbow trout, sea bream and sea bass in Europe; catfish, Aquaculture is booming: salmon in Norway, Scotland, Chile, New Zealand and Australia; carp in central and Eastern Europe; catfish, carp and other freshwater species in China and southeast Asia; rainbow trout, sea bream and sea bass in Europe; catfish,

In Asia, where a wide variety of fish species is raised, along with crustaceans (prawns, lobsters, shrimps) and shellfish, fish farms occupy saltwater, freshwater and brackish environments. Many are built on land, others occupy lakes and rivers, as well as estuaries, harbours and bays.

Environmentally, there is plenty to be concerned about when it comes to aquaculture, particularly fish farming, though environmental standards and operational practices vary widely. The main issue is overcrowding, which leads to disease, high parasite loads, high stock mortality and localised pollution, even when farms are situated in open water.

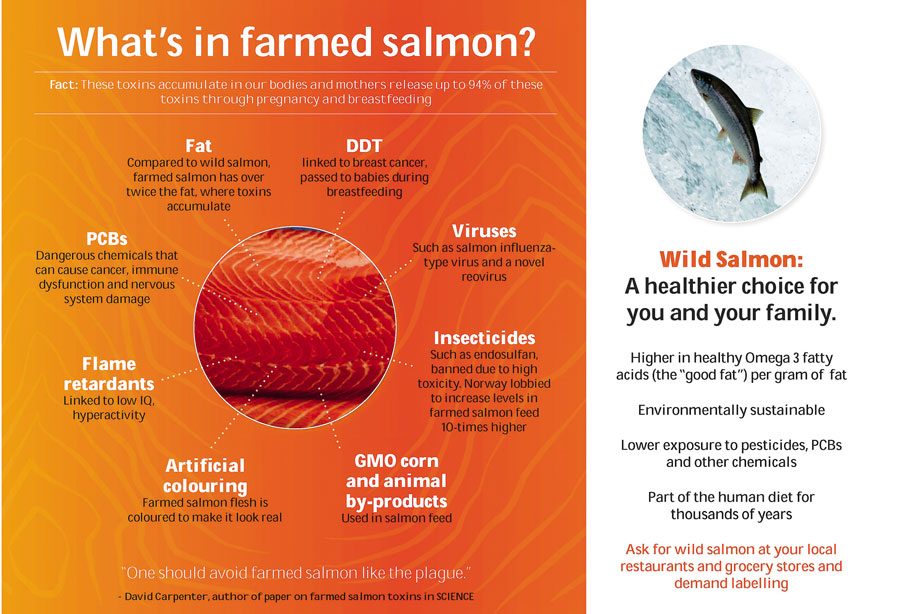

In the US and elsewhere there is strong opposition from some groups to the consumption of farmed fish due to health concerns.

Environmental and stock health problems are most acute in ponds and other closed systems where water turnover is low. Fish such as basa, carp and tilapia, as well as some species of prawns, can tolerate poor water quality, which is why they are popular for land-based fish farming. Much of the basa farmed in Vietnam lives in water drawn from the Mekong, one of the world’s most polluted rivers, as do many of the prawns sold in New Zealand.

Faeces and uneaten food filters down through sea cages to the seafloor and builds up on the bottom of farm ponds where it rots, depleting oxygen and killing bottom-dwelling plants and animals. In New Zealand, monitoring has revealed two main impacts of salmon farms: raised copper and zinc levels, and nutrient enrichment caused by fish waste.

To a lesser extent, the same thing happens with mussel farms and oyster leases, though shellfish are not ‘fed’, instead filtering what they need from the water. They do, however, produce waste which accumulates on the bottom.

Processed pellets are used in fish farming, which may incorporate cereals, various animal and plant proteins and lots of supplements. Until recently fish meal and fish oil were the main ingredients, but fish meal/oil is processed from wild- caught fish, much of it the natural food of the commercially important fish species we like to eat. Turn all the anchovies and sardines into fish pellets for farmed salmon, trout and catfish and there is nothing left for the tuna to eat.

Marine fish in ocean cages

Marine fish in ocean cages

In recent years rising prices for fishmeal and fish oil, resulting of over-harvesting wild fish, have forced the industry to look for alternatives – cheaper by-products from abattoirs and plant materials such as faba-bean meal, added for extra protein and to act as binding agents.

New Zealand farmed salmon eat pellets manufactured in Australia mostly from abattoir byproducts – poultry off-cuts and feathermeal, as well as bloodmeal from cattle, pigs and sheep. Only a small proportion (around 10%) is fish meal and fish oil (7%) – mostly from Peruvian anchovies.

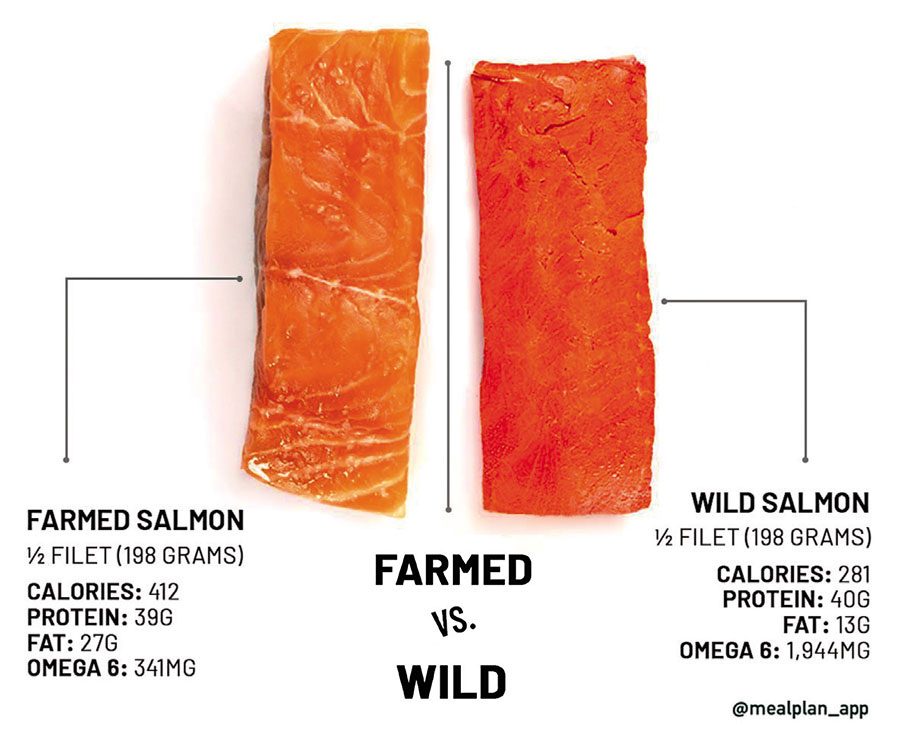

The desirable pink flesh of wild salmon results from eating krill and other crustaceans; farmed salmon has pale flesh unless artificial colour (astaxanthin) is added to the feed. The flesh of farmed salmon also contains much less Omega-3 and Omega-6 fatty acids wild fish synthesise from their food, and almost twice the fat. The consumption of these Omega fatty acids is touted as an important health benefit of eating fish.

Even hardy species need help to survive in a lot of fish farms, so antibiotics, vaccines and chemical treatments are routinely used to control disease, parasites and pests. Traces of these can persist in the farmed animals we eat and some of them are known to be carcinogenic in humans.

A freshwater basa catfish

Unlike basa or carp, salmon are anything but hardy, making them quite a challenge to farm. Salmon farms overseas have been devastated by diseases associated with high stocking rates and stressed fish. Diseases spread quickly through sea cages and beyond to infect wild salmon populations. Salmon farm operators use antibiotics and vaccines to control diseases, though the salmon industry in New Zealand claims to be antibiotic free.

Fortunately, New Zealand-farmed chinook (King) salmon, a Pacific species, seems to be somewhat resistant to the diseases affecting Atlantic salmon, which make up the bulk of farmed salmon around the world, including Australia.

Salmon farming in New Zealand is facing challenges due to its environmental impact and from climate change too, with warming water increasing fish mortality. The water temperature in the Marlborough Sounds, where the bulk of New Zealand salmon is farmed, is close to the upper limit for chinook salmon in a normal summer.

Farms in the Marlborough Sounds are managed to minimise environmental effects by controlling feed levels and fallowing low-flow sites to give the seafloor time to recover. According to the farm operators, a farm left fallow can regenerate in two to 10 years depending on the water flow.

Nonetheless, in 2011 several sites exceeded guideline levels for copper and zinc. One was found to be operating at the limits of “maximum acceptable environmental quality standards” , its feed inputs described as “beyond the assimilative capacity of the site”. The monitoring report on another Marlborough Sounds farm described it as “highly-impacted” and “biologically impoverished beyond the point at which wastes can be efficiently assimilated”.

Intensive fish farming beside a river somewhere in Southeast Asia.

While improvements have been made in salmon farm management since, pending resource consent there are plans to relocate some of the worst-affected farms to locations with better water flow, or to completely new cold water locations in Southland.

Aquaculture undoubtedly has considerable impact on the environment and its products are not always especially healthy for consumers. I doubt aquaculture will halt or even slow the ongoing rape of the world’s oceans or encourage more sustainable practices for wild fisheries. My guess is that wild seafood will become a luxury item – it’s already happening – and most of the seafood we consume will be farmed.

If that becomes the reality, just like eating tuna, wahoo, marlin and other large fish which concentrate heavy metals, dioxins and other pollutants in their bodies, eating farmed prawns – or farmed salmon – probably isn’t something you should do every day.

In the meantime, I’ll stick with fish I catch myself. BNZ