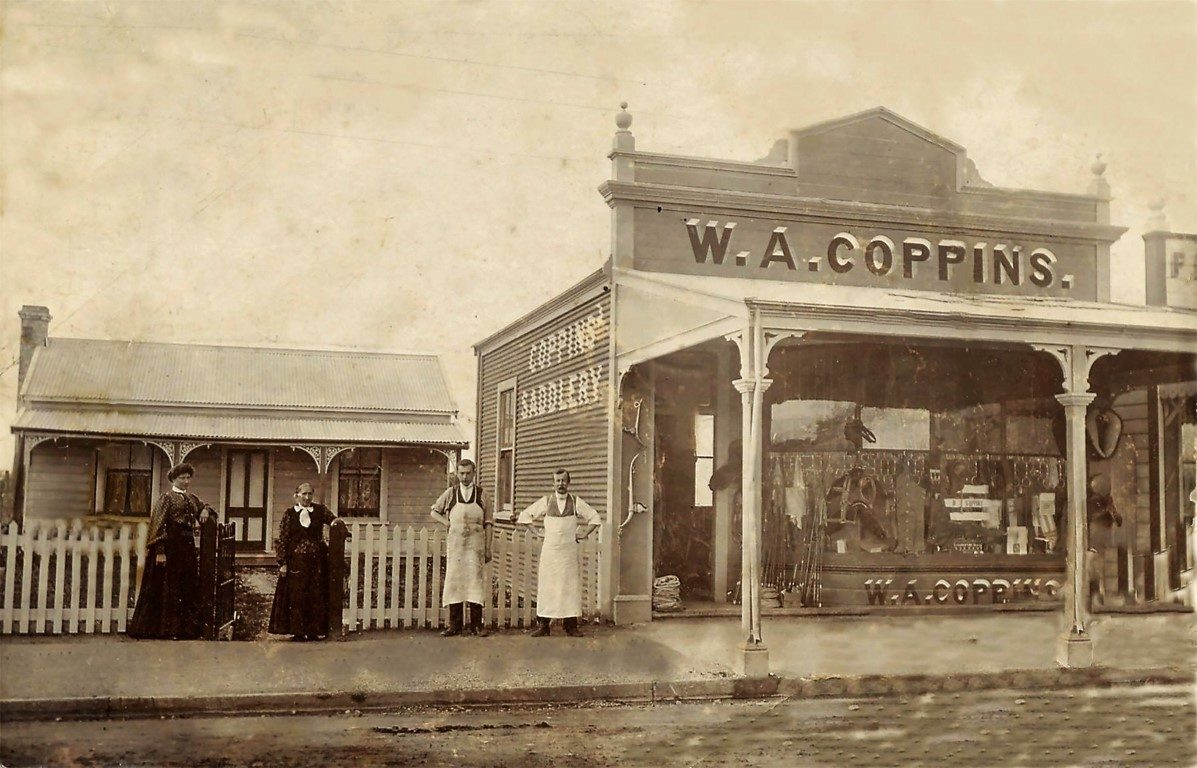

The best sea-anchors in the world are made in New Zealand. By Coppins, a family company that’s been in the same site in the main street of Motueka for four generations and over 120 years. By Alex Stone.

Our story angle on this one: “Your product saved our lives.”

It’s the kind of story the good folk at Coppins hear regularly. Still, they haven’t lost the emotion of it at all. When Lesley and I made a pilgrimage of thanks to Coppins, we were greeted with hugs and misty eyes. This is a business with heart. And one based on many years of brave innovation.

It all started in 1898 when William Arthur Coppins, whose parents owned the Motueka Hotel, was forced to go out and work at age 10 when his mum died. He took up an apprenticeship at a saddlery. Which, over time, turned into the horse tack emporium in the main street. When his son Leo took over the business, he also started supplying canvas products to local shipping – mostly tarpaulins to protect deck cargo and cargo hold covers. He also diversified into making canvas fruit picker’s bags. Today the Topo 2000 is the gold standard bag used by New Zealand’s Kiwifruit orchardists.

In 1965, Coppins began making drogues for the West Coast tuna fishing fleet. The word got out via VHF. One skipper telling another how comfortable he was 200 miles offshore. That envious skipper radioing ahead to Talleys, the fishing company for whom they worked, to order one for his boat on his company tag. And so it went.

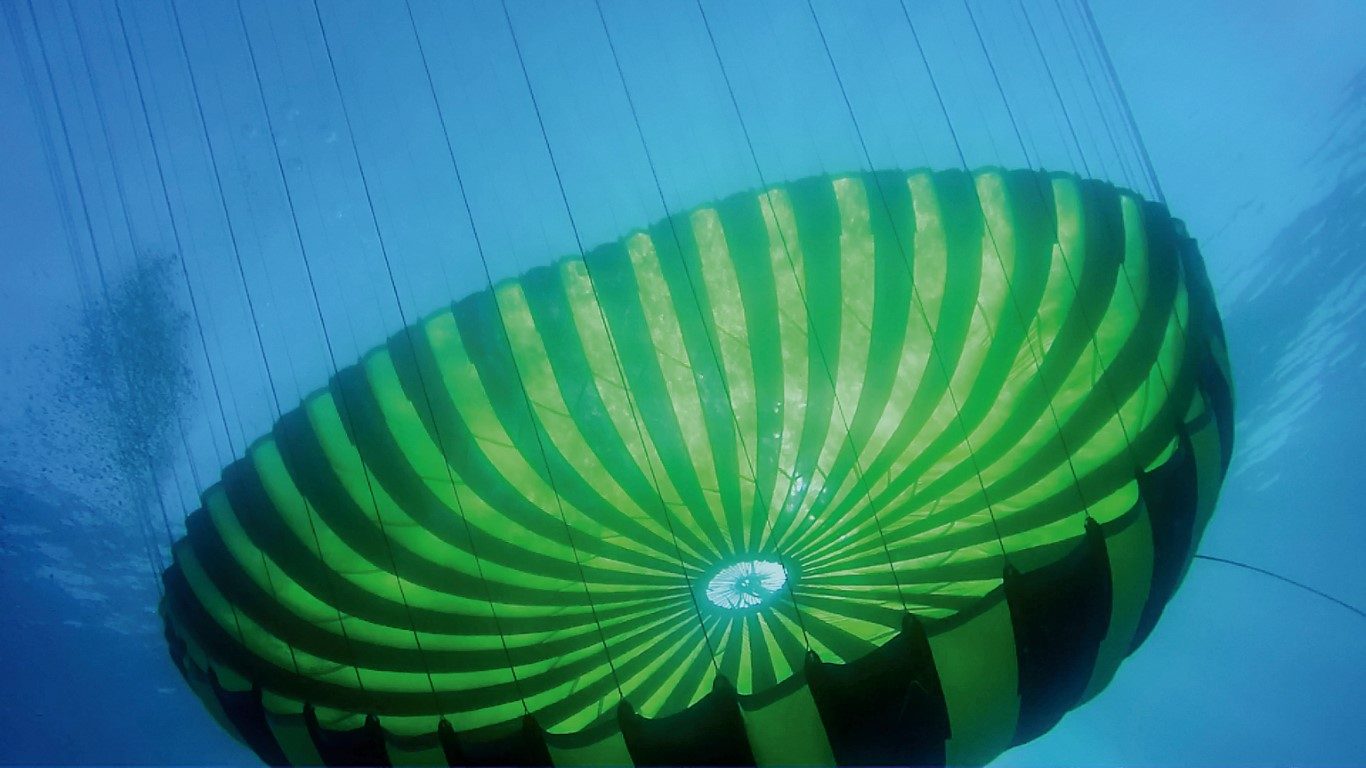

Then Bill, third-generation Coppins, had the idea to make the drogues lighter and bigger, modifying a late 1960s parachute design and employing a stretchy type of ripstop nylon. These evolved into the full-on sea anchors that make Coppins genuinely world famous today.

To be clear, a proper sea-anchor is designed to hold your boat stock-still at sea; and is deployed from the bow, so your boat – as it’s designed to do – is facing the seas. And because you’re standing still, the force of the waves is relegated to simply the up and down motion. The sum of these elements is the essence of what makes sea-anchoring so safe.

Drogues are designed to slow down a boat while still moving and retaining steerage. For this reason, drogues are deployed from the stern of the boat.

Coppins sea anchors really do work. Extreme testing by one of their biggest clients, the US Navy, saw them dropping huge Coppins sea-anchors from moving ocean tugs. One pulled the tug up so sharply, a 241-tonne Dyneema anchoring rope broke! Coppins’ sea-anchors can hold a US Navy destroyer still in an oceanic storm, or allow a deep-sea factory ship to hold station over a seamount or in the middle of a working fishing fleet.

The secret to the efficiency of the Coppins Sea Anchors is that each is sized for your boat. For our 12m cruising cat, which weighs a little over four tonnes, Coppins specified a sea-anchor of 4.5m diameter.

Bill continues to refine the sea anchors, after conducting extensive tank testing trials at the Naval University in San Diego and ongoing testing back home in the Motueka causeway channel which runs at seven knots.

“Cost effective, eh.” Another of Bill’s laconic comments.

Bill Coppins is entirely self-taught in all of this. In true Mainland style, he humbly says “No I’m not an engineer. I’m nothing.”

I beg to differ. Navies, professional fishers and yachties around the world provide testimonials to his extra-ordinary sea anchors. He’s also a life member of the Outdoor Fabrics Products Association of New Zealand.

Coppins now employs up to 18 staff, building their Sea Anchors from a fabric custom-made exclusively for them.

In the 1970s, the company also began selling outdoor sports gear like kayaks and mountain bikes. Bill’s son Ryan is set to take over from his father sometime in the future, becoming the fourth generation of Coppins to run the business.

A last word from Bill: “It’s more like an adventure [making sea-anchors]. Compared to fruit picking bags

OUR STORY — Coppins in a Gale

Here’s our story about the use of a Coppins Stormfighter Sea Anchor, during a stern Tasman crossing:

On the second night of the first gale we sea-anchored for the first time. Only two helmsmen on the boat were confident sailing the boat through the nights in the increasing wind and sea (the boat was surging down the waves at up to 20 knots, under just a storm jib), and were getting very tired.

The sea-anchor deployment system worked perfectly. The big parachute is tipped overboard in a bag from the cockpit, then drifting away from the boat while slowly unfurling, the rode and bridle breaking away from cable ties on the stanchions and then being paid out from the foredeck, the boat turning head to wind and lying quietly as the parachute takes its grip in the water.

The only downside of the sea-anchor is that it imparted a motion that was sea-sicky for me (unusual!), but had no effect on the other crew. Apart from forays to the foredeck foul-weather-geared and clipped on to check the bridle ropes and fairleads, I had to spend most of sea-anchor time head down. The crew read books, played cards, slept. We checked the bridle for chafing, often.

Retrieving the sea-anchor was a simple enough process, that had to be done methodically and sequentially. Motor up to a floating buoy behind the anchor, collapse it from behind, pull it aboard, and re-pack the parachute, flake and re-bag the rode and bridle, and set the system up again along the side deck guardrails. That takes an hour or so.

A second gale came pretty much as a continuation of the first, forcing us to sea-anchor again. It was a strange feeling being so immobile (in terms of co-ordinates, certainly not in terms of up-down motion) in the middle of the ocean. Our GPS devices showed we moved nowhere in the night. I dreamed of anchoring near a shoreline somewhere. The boat would take an occasional slap of a whitecap, but at this stage nothing serious, despite the 60-plus knots blowing outside.

On sea-anchoring

At first, I had been sceptical about getting a sea-anchor. I remembered these being not much more than conical drogues, inadequate to hold a boat. (In fact, you’ll still see these in some chandlers. I think they’re falsely advertised).

I recall stories of yachts slipping backwards down the face of steep waves, putting the rudder under immense pressure, while supposedly ‘at anchor.’

Lesley wouldn’t let this issue lie unresolved. She believes in credible research. She checked sea-anchors out – and I am more than relieved she did.

She found out that the international development of parachute sea anchors has been led by Coppins. They developed a formula for sizing and constructing nylon parachute anchors that will hold your boat as an anchor really should. That is, they will hold you still.

No backwards sliding.

In discussions with them, I asked for the bridle ropes to be extended, so we may lead them over the catamaran’s bows and back to the genoa sheet winches. This I anticipated would be safer for adjusting the length of the bridles, from the safety of the boat’s cockpit.

It was a worthwhile precaution.

We adjusted the bridle lengths by 20cm every few hours to minimise chafing in one spot at the carabiners. This appears to have been an added caution, as there was no visible chafing on these ropes.

The deployment and retrieval methods for the sea anchor were clearly laid out in the Coppins brochures and worked flawlessly. It is well worth setting up the deployment system before leaving the dock. I did it all in the first gale – not ideal, but manageable.

The boat did swing a bit at the end of the sea anchor bridle, as cats at anchor normally do. But not enough to put us dangerously askew of the main swell direction. It was the Tasman’s sea-state that provided the mix of wave directions.

I understand some monohull sailors deliberately offset the anchor rode to have the boat lie at a consistent angle to the waves. For us, straight on to the prevailing wave direction was what we felt most comfortable with – at a slight angle, we may have had fewer slaps up under the bridgedeck (with the windward hull sheltering the tunnel to some extent). But we couldn’t really test this with any certainty.

The precision of current GPS positioning systems provided interesting feedback on the efficacy of the sea anchor. On our first two nights at anchor, we did not move position at all.

At our position north of NE of Cape Reinga, we were actually towed about two nautical miles per night into the gale (which peaked at about 70 knots), as a result of the current moving west to east in those waters.

I think the sea-anchors are products that should be available for hire. While it possibly saved our lives, our sea-anchor won’t be used for a while. It could, however, help other ocean-crossing sailors.