The glittering world of the America’s Cup with its multi-million dollar campaigns, champagne sponsors and privileged participants, might seem completely incompatible with a charity school in central Africa. But Emma Outteridge, a Kiwi woman with a strong sense of compassion and a drive to make a difference, has brought these two vastly different worlds together and written a book about the experience. Sarah Ell reports.

Outteridge was born in Nouméa – while her Kiwi parents Ross and Jo Blackman were cruising the Pacific. The Blackmans had traded life ashore for a 32-foot cruising yacht in 1981 and set off with “no set plans but a vague hope of eventually reaching Hawaii.”

Ross was a sailmaker and an experienced sailor, but Jo had never even been on an overnight passage and learned sailing and navigation (pre-computers) as they went along. It’s the kind of can-do attitude you see reflected in Outteridge’s own approach to life.

The family eventually set up base in the Bay of Islands, with Ross working in marine sales. Life was simple enough until he got the call from his friend Tom Schnackenberg, to come and run the New Zealand Challenge sail loft in San Diego for the 1988 “big boat” America’s Cup attempt.

Bitten by the America’s Cup bug, the family moved back to San Diego for the 1992 challenge, and the 1995 victory which saw the Cup come to New Zealand for the first time, where Ross became chief executive of Team New Zealand.

Emma and Nick grew up as ‘Cup kids’, living in an apartment complex with the other Kiwi families and eating communal meals at the team base. The high-stakes, big money world of grand prix yacht racing was all they knew.

“Growing up in the America’s Cup world, as a little kid I just thought that was what everyone did, that you follow this sailing event around the world,” Outteridge says. “Then obviously you grow up and realise that’s not the case.

“But when I went to university [in Wellington] I really had a bit of an awakening there. Being in the university scene, you’re learning all of these new things, and my eyes were opened to the fact that there was whole wide world out there, one that didn’t revolve around the America’s Cup and sailing, but also that beyond New Zealand there were a lot of people who were doing it quite tough around the world.”

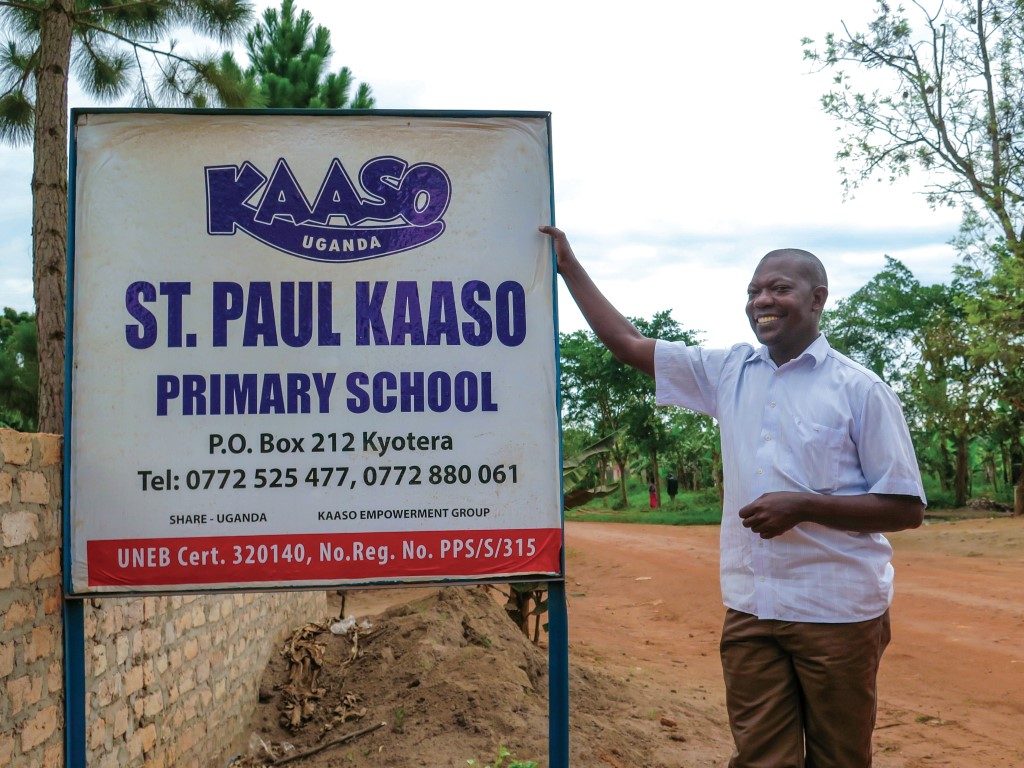

She became determined to do something to make a difference, to use the happy accident of her birth into a life of privilege to make change in the world. In 2009, after some searching, she signed up to spend six months volunteering at St Paul KAASO, a charity primary school in near Lake Victoria in southern Uganda.

KAASO was set up by a Ugandan couple in 1996, initially to cater for children orphaned by the country’s HIV/AIDS epidemic, but then taking on other local children whose parents wanted them to have a quality education and escape from a life of poverty.

“Through my extensive childhood travelling with the America’s Cup, I felt like I had been to so many different places and seen different things, but when I arrived in Uganda I was completely blown away by how different everything was,” she says. “There was no common point of reference, so it was such an extreme culture shock.”

At first, Outteridge and her fellow volunteers (the ‘Kiwi girls’) found themselves fish out of water, unsure of how to fit in to the local way of life and struggling to find the best way to be of assistance at the school.

Then, having found her place and realising she could make a difference by sponsoring a local child, Henry, through secondary education, she found the shift back into ‘real life’ – working in hospitality for the Louis Vuitton series in Europe – just as difficult, if not more so.

“If I thought I was unprepared for the shock of moving to Uganda, I was completely unprepared for the shock of returning,” she says. “I was just completely floored by how hard it was transitioning back into what had been my normal life.”

Outteridge says she was constantly converting how much things cost into Ugandan currency and working out how much maize she could buy for the same amount, overwhelmed by emotion and not knowing what to do next. Caught between these two vastly different worlds, she was torn between which one to give up when she realised that, in fact, she could do the most good by being a bridge between them.

“It was the community of sailors that helped me to realise it,” she says. “Once I got over the initial shock of not being able to talk about what I’d done without bursting into tears all the time, I couldn’t stop talking about it. These people made me realise that I didn’t have to give up one world or the other, and that the most valuable way for me to help was being between these two worlds and connecting both sides.”

Her mission became sharing her passion for and knowledge of KAASO with those much more fortunate friends involved in the international sailing community and encouraging them to financially support Ugandan children through higher education.

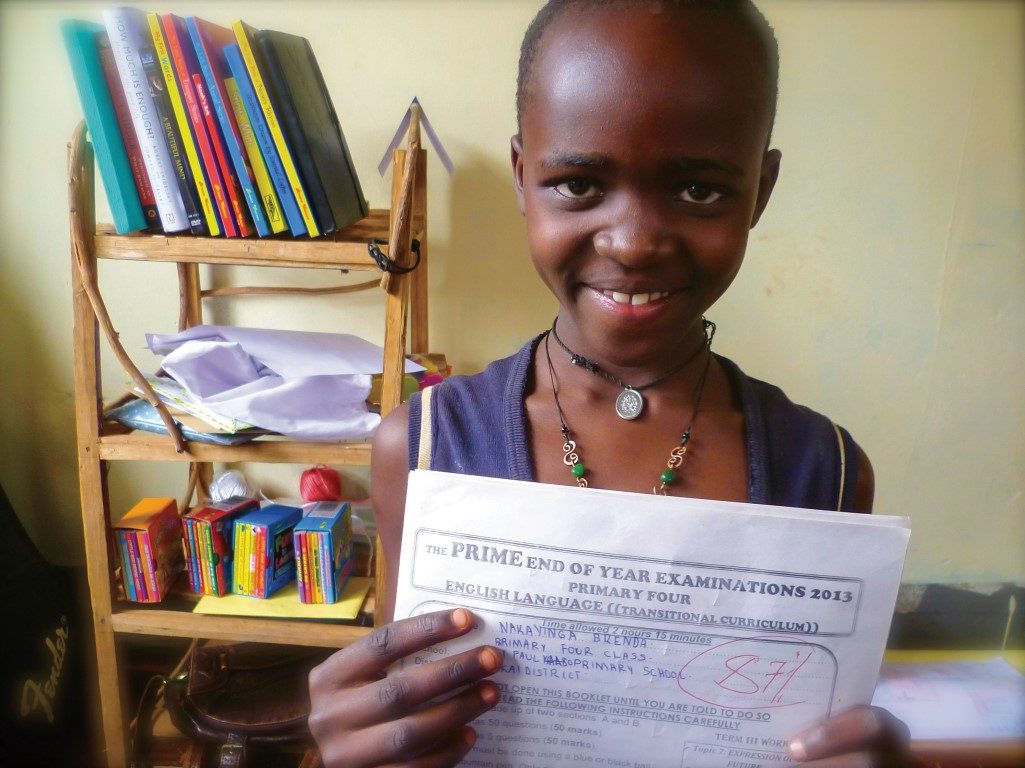

Through the Kiwi Sponsorships programme Outteridge founded, more than 70 children have been able to access a higher quality of life, including her own Henry, who has now completed university and is working in a lab developing vaccines against HIV/AIDS.

“I found people really wanted to help and support it because they knew how much time I had spent there and the connections I’d made, and that this was something that was legitimate and trustworthy and honest, that they could support and that they could grow to care about.

“At the beginning I felt like it would be a one-way flow, helping the children in Uganda, but over time I’ve realised that the flow is both ways. Through their sponsorships, these people are able to teach their children about the value of education and the value of things they might take for granted. They have the chance to be involved in something significant.”

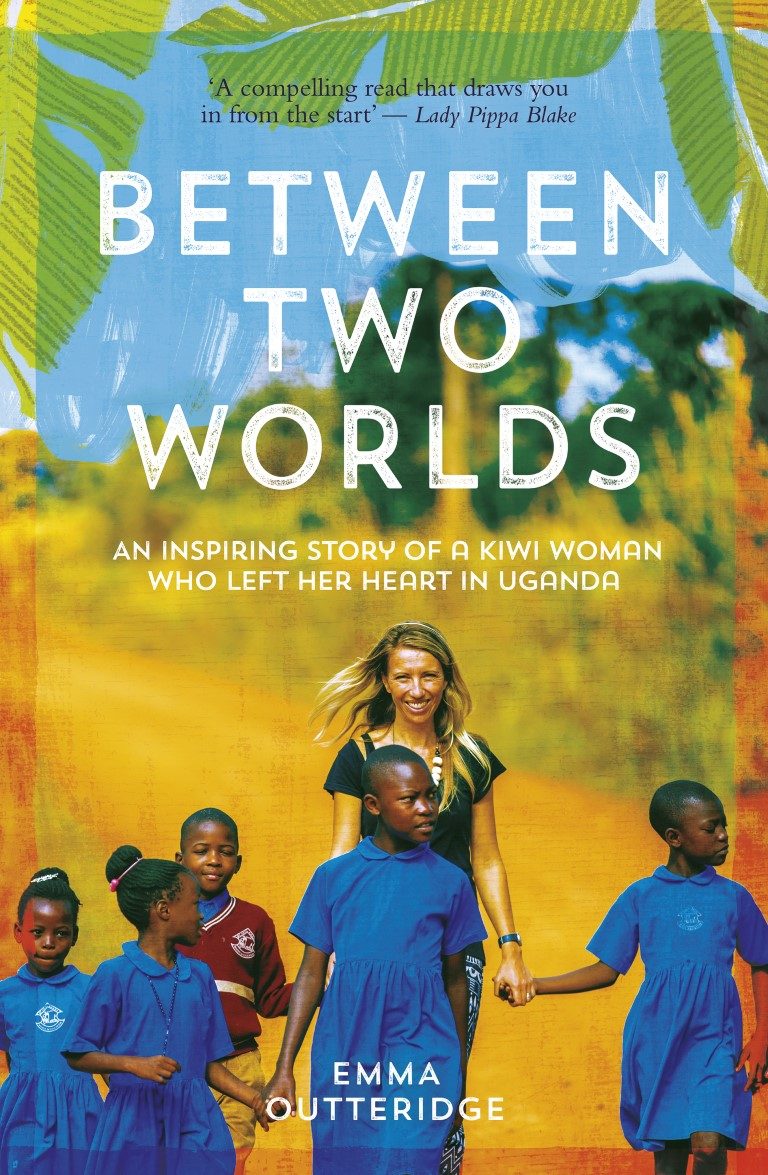

Her book – Between Two Worlds – paints a vivid picture of Outteridge’s time in Africa, drawn on extensive diaries she kept at the time. “It’s been quite a journey – I’ve been writing this book for twelve years, and started it when I was first in the village,” she says. “I thought it was such a phenomenal story. I had a huge stack of diaries and I scribbled down everything anyone said.”

But despite writing it in fits-and-starts, “on scraps of paper and boarding passes and serviettes in cafés around the world”, it wasn’t until last year that the whole story really took shape. With her husband, Australian sailor Nathan Outteridge, and their toddler son Jack, she flew into Auckland in March 2020 for a visit which was only supposed to be a few weeks long – and we all know what happened next.

“It was really because of Covid that the book actually happened,” Outteridge says. “All of a sudden we had a lot of time. I had a husband at home who was unable to work, so I had time to focus on the book and get it out into the world.”

Nathan Outteridge is one of the world’s top sailors, winning gold in the 49er class at the London Olympics and silver behind Peter Burling and Blair Tuke at Rio. He sailed with the Artemis team in the 2013 America’s Cup in San Francisco and 2017 in Bermuda, and is now the skipper of the Japanese team on the SailGP circuit.

After a 15-month Covid-enforced break in New Zealand, during which their second son, Charlie, was born, the Outteridges are now back on the road on the other side of the world, with SailGP events scheduled for England in late July, Demark, France and Spain before the two southern hemisphere events, in Australia and New Zealand.

“We’re so lucky that everyone is racing again. SailGP is operating in strict bubbles, which is great because it means the show can go on,” Outteridge says. “We’re looking forward to following the circuit around. We can’t physically attend any of the events because the sailors are in these bubbles, but we will be cheering from afar.”

And you can be assured, she’ll be taking every opportunity she can to spread the world about KAASO – and keeping up her good work trying to make life a little better for those less fortunate than herself.