Blue Duck – a 16-foot fantail clinker workboat built in 1895 – received the Innovation Award at this year’s Lake Rotoiti Classic and Antique Boat Show. Yes, you read that right – a 126-year-old boat was recognised for her innovation. She’s electric-powered. Story by Lawrence Schäffler.

Owned by Nelson’s Peter Murton, Blue Duck is no stranger to the Lake Rotoiti show – she’s been displayed there previously and has won various awards. But this year’s gong is a little special because – if the research is accurate – her new propulsion is her second electric system. The first was nearly a century earlier. This latest version marks yet another chapter in an extraordinary life.

The little clinker’s been fitted with numerous propulsion systems over the years but, tantalisingly, the research suggests she was first electrically-powered when big, heavy batteries and equally big, heavy DC motors were only just becoming established in New Zealand.

Murton has owned Blue Duck for about 12 years and makes his living restoring classic boats (more on this in a moment). Saving her and tracing her history, he says, uncovered plenty of scarcely-believable twists and turns. This duck is one tenacious survivor.

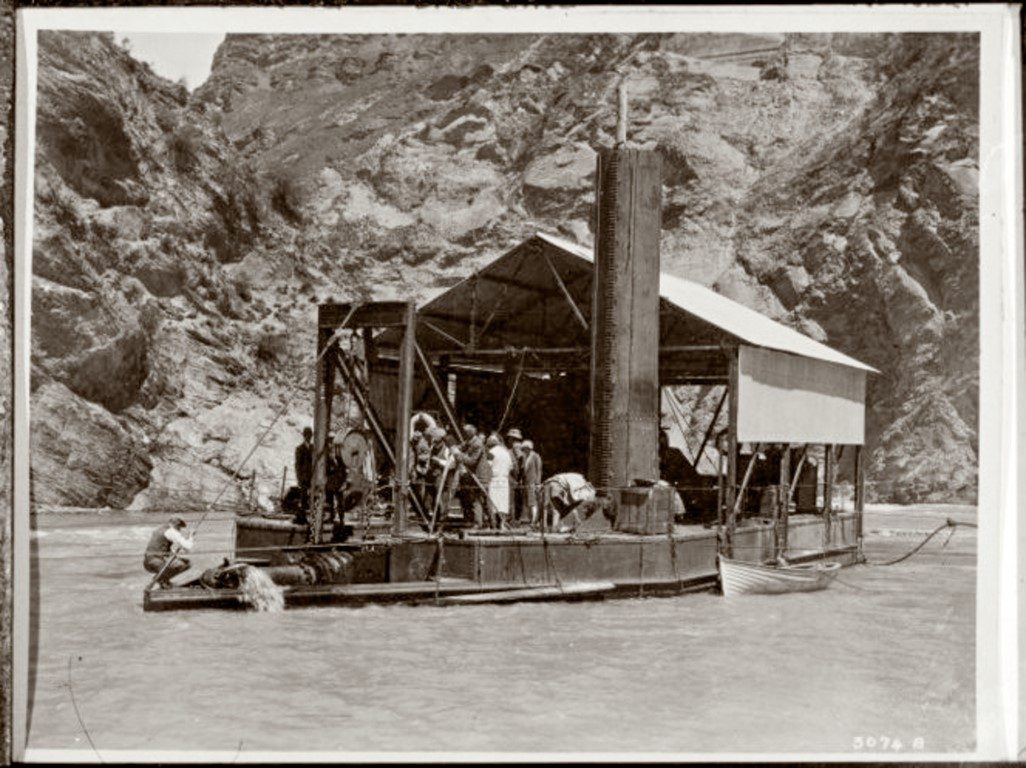

She was built by the Knewstubb Brothers in Port Chalmers and by 1907/8 was serving as a workboat on the Shotover River, a tender to a gold-working dredger anchored at Maori Point (see photo above).

Museum records show she was initially powered by a Union oil-fired engine, ferrying workers between the shore and the dredger. The dredger, for its part, was an experimental vessel using electricity for the gold recovery process – and there are suggestions that around 1907 Blue Duck (her original name) was eventually retrofitted with batteries and a motor.

Despite her advanced technology, the dredger was a flop and in any event was wrecked when a massive flood washed her downstream. From this point Blue Duck’s trail runs cold and only picks up again in the 1970s when she turns up on Lake Wakatipu, converted to a day-sailer with a gaff rig, cabin, fixed keel and a lump of railway iron for ballast.

In the mid-1980s she sank at her mooring. Some kindly soul salvaged her and took her to Cromwell for a period, before she moved on to Alexandra where she became a garden ornament for a further 15 years.

Murton acquired her when that owner called: “I have a boat in our garden. I think she has a lot of history and shouldn’t be sitting here. She needs to be restored.” So Murton went to fetch her. And yes, Blue Duck was in a bad way, derelict and very weather-beaten.

“But, remarkably for her age,” he says, “most of her kauri hull was OK – though I had to fit new garboard planks, new ribs and recycle the kauri deck. The entire boat had been covered in fibreglass at some point – no doubt to stop the leaks. It looked awful but, ironically, I think the sheathing helped to preserve her. After stripping away the fibreglass I was amazed to discover she didn’t have any rot.”

With her rejuvenated hull he opted to repower Blue Duck with technology from her era – a steam engine. It just so happened that there was a 2.5hp Hasbrouck twin-cylinder steam engine and boiler sitting in his workshop (built by Murton’s engineer dad many years previously).

While this worked well (using the boat’s original 17in x 30in prop) the boiler presented a few safety concerns. These could only be addressed by adding more weight – far too much weight for the little clinker.

The Hasbrouck was replaced by a 1907 two-stroke, single-cylinder 8hp Gray petrol engine. But despite much fiddling and cursing, the Gray proved hopelessly unreliable. It too was abandoned – for a twin-cylinder 8hp Stuart Turner P55 petrol engine. It wasn’t much better.

Eventually, Murton’s son (an engineering PhD student) suggested a more radical solution – a small, 36-volt brushless motor – running that old prop through a 14:1 reduction gearbox. It worked a treat.

Power comes from three deep-cycle batteries (105-amp hours) and the system uses a rheostat for a throttle (it also switches between forward and reverse). The little motor drives the boat to her hull speed – about 5.5 knots – and the batteries are good for about eight hours.

Blue Duck, finally, is back in her element, and relishing the silence.

Timbercraft

The company’s called Murton’s Timbercraft and, as the name suggests, his business covers more than classic boat restoration. He also crafts period furniture from recycled native timbers, though boat restoration/building accounts for 90% of his work.

His marine career began – at age 15 – with the restoration of 14ft clinker, helped by his woodworking teacher. She was powered by a 5hp single cylinder Simplex engine.

Various boat restoration projects followed over the years – mainly for friends – but things really took off when he was commissioned to build a 19-foot John Wellsford Whaler (lapstrake plywood construction) for a friend. “Things just snowballed – all via word of mouth.”

Today, visiting Murton’s Nelson yard is a bit like walking into an open-air maritime museum. Vessels are stationed all over the premises, all awaiting their turn in the workshop. Some are basic repair jobs but most are full restoration projects. The clients are located all around the country.

Among the current stock is the original 12-foot clinker tender from the 1909 scow Te Aroha which operated up on the Kaipara Harbour. The tender is his (not a ‘paying’ job), so will remain hanging in the rafters and until more pressing jobs are out of the way. It has already received new ribs and will be fitted with new planking.

In another corner is a 1930s kauri-planked ski-race boat – provenance unknown. “Based on the marks left from the original engine bearers,” says Murton, “I’d say she was first fitted with a WW1 aero engine – and there have been at least three different steering systems.

“She also arrived with an interesting transom. Given the twin exhaust ports we can guess she might have been repowered with a V8 at some stage. There are other mounting points as well, suggesting a different engine mounted further forward. The transom also has a cutaway for an outboard…”

Ulva is a 19-foot clinker built on Stewart Island around 1900 – it’s believed she operated as a ferry, carrying passengers between Ulva and Stewart Islands, and was powered by oars and sails. Tough work in that part of the world!

Murton’s bias to early 20th century vessels is obvious. “I like the era because it represents a part of our maritime history that’s rapidly disappearing. A lot of the old boats meet their ends in bonfires, or are buried under hedges, or left to decay in sheds. I want to help preserve the heritage – and I have the traditional boatbuilding skills to do the work.”

Timber fingerprints

Many of the projects are delivered by an owner with scant knowledge of his boat’s history. “So it often takes some detective work to try to fill in the gaps,” says Murton. “Fortunately for us, timber offers a few clues.

“With many New Zealand boats from that era, you can usually tell where they were built by the timbers that were used – a bit like DNA profiling. Around the upper part of the South Island, for example, builders typically used kanuka for all the knees and natural crooks and stems. Further south, though, they would use more kowhai and rata. Kauri use was widespread throughout the country, so by itself a kauri hull doesn’t help me much.”

Even so, identifying very weathered and aged timber can be difficult, and Murton has on occasion visited the local Woodworkers Guild in Nelson for help, exploring its library and discussing a timber’s grain, texture and weight with the experts.

Though traditional skills such as caulking and scarfing might have been used to bring an old dame back to life, Murton likes to use more modern, robust paints and varnishes to make sure they’re preserved for many more years – “my go-to default is Altex – they make great products.”

For more information visit www.murtons.co.nz