A self-described adventurist, Koper enjoys sailing in some of the planet’s most obscure (and extreme) places. Let’s see – his resumé includes extensive sailing in and around the Arctic Circle, transiting the Northwest Passage, two previous trips to Antarctica (one beyond the 78th parallel), sailing around Cape Horn (twice) – and now, a circumnavigation of the frozen continent.

I thought asking ‘why’ would be a good way to start the interview.

“I like challenges – and I love Antarctica.”

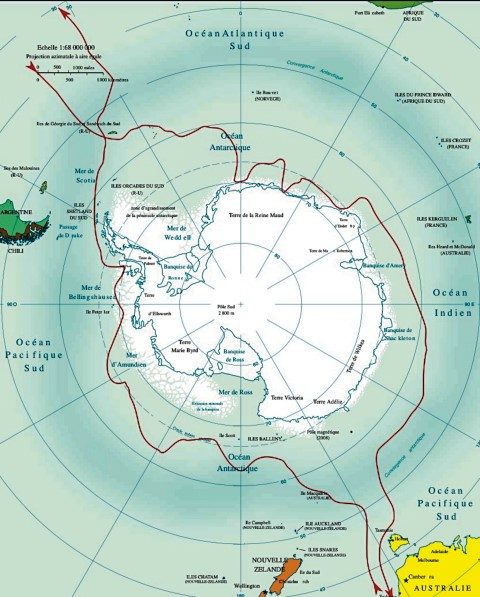

This circumnavigation – 72 days, non-stop under sail – has been ratified by Guinness World Records and the World Sailing Record Council as the ‘southernmost’ circumnavigation of the continent by a yacht. The boat remained just off the ice, sailing clockwise (west-to-east) between the 60th and 70th parallels for the entire voyage. The previous record (in a much wider band, between the 45th and 60th parallels), was 102 days.

To get around the ice-cap within the narrow ‘summer’ window available to sailors, the boat left Cape Town on 23rd December 2017. She arrived in Hobart, Tasmania, in April, nearly 16,000 miles later.

Koper’s choice of vessel for these adventures is a 22m Oyster 72 (he’s owned various other vessels before, including a smaller Oyster, Katharsis I). Built in GRP, Katharsis II is a heavy, robust yacht (50 tonnes) and, though she doesn’t have strengthened bows, her 225hp Perkins engine is perfectly adequate, he says, for pushing through the ice. Since her launching in 2009, she has carried Koper some 120,000 nautical miles.

Sailing around Antarctica sounds hellish – well, a coldish hell. Is it?

“Actually, the wind in the roaring forties and furious fifties is much worse. Around those latitudes the prevailing wind is westerly, and it’s rarely mild. But once you slip below 60 South the wind is much more variable – about 40 percent headwinds, about 30 percent following, and about 30 percent very little wind.

“In fact, we were becalmed on more than a few occasions, and because we wanted to do the circumnavigation under sail only, it became a little frustrating. But on the other hand, we also sheltered in the lee of icebergs when the weather turned nasty. So it’s very mixed.”

Katharsis II is equipped with sophisticated weather monitoring gear – does that help in plotting the route?

“To a limited degree. The weather radar and satellite imaging show an approaching low, but its position and, more importantly, its depth, aren’t particularly precise. And the weather forecasts – such as they are – aren’t really reliable. Besides, the weather changes very quickly down there.

“Judging the ice situation is a little more tricky. There is no ice forecast – only satellite maps. So while you’re seeing the ice field in real time, you have to make your own judgements about its movement and likely change in direction.

“Even though we remained between the 60th and 70th parallels – supposedly well clear of the ice, we still came into contact with it. Icebergs aren’t the problem – they’re easy to see and you can sail around them – or, indeed, shelter behind them.

“But the growler ice – just on the surface – is much more difficult to see and it’s very dangerous. On three occasions we were semi-trapped in it, but fortunately managed to sail free. Sailing through ice demands a gently-does-it strategy – you push your way through. Speed is not a good idea.”

The boat was also covered in ice from time-to-time.

“Even though her Dyneema sheets handle the cold better because they don’t absorb as much water, they still froze and it’s very difficult to work with solid lines. Some of the instruments were also affected – including the anemometer. So you don’t really have an accurate grasp of the wind’s strength. The dial might show 25 knots – but it’s actually blowing 40 knots.

“We weathered 18 storms during the trip. Fortunately, the Oyster is an excellent heavy-weather vessel. In 50-60 knots she is very happy with a fourth reef in the main – that’s about the size of a trysail – and a well-reefed staysail.”

Still, for all the hardship, says Koper, Antarctica is one of the most majestic parts of the planet – “it’s difficult to describe the silence, the grandeur, the clarity of the colours on a sunny day, the raw power of the elements. Sailing among the whales is a wonderful experience, and the birdlife is sublime.”

RESEARCH

While the record-breaking circumnavigation was the prime focus, Koper also used the voyage to participate in two oceanographic projects. One was deploying three sophisticated buoys which will collect various types of data over the next few years; the other collecting water samples for monitoring the presence of micro-plastic particles.

“We were keen to do something to help with research into areas of the Southern Ocean which are rarely visited – if ever – by scientists. And the research was conducted under the auspices of the Polish Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Oceanology. Among our crew members was one of the Academy’s professors, Piotr Kukliński.”

The buoys will drift around the continent for a number of years but will spend much of the time under water. They are programmed to sink to depths of 2,000m, collect data, and then resurface to transmit that data to satellites. Each will submerge and resurface some 100,000 times per annum.

“Specifically, the buoys will monitor sea temperatures at various depths, the speed and direction of ocean currents, salinity – that sort of thing. They will help to identify changes in climate and give scientists a better idea of how the continent might be affected over coming decades.”

Checking for the presence of micro-plastics, says Koper, was a little easier.

“Going through the convergence zone, the objective was to check for micro-plastic particles. We chose 10 locations staggered around the continent. We would slow the boat, deploy a specialist net and drag it for 30 minutes to collect the samples. These have been sent to land-based laboratories for analysis.”

Anyone who’s spent any time bluewater sailing will appreciate that when a crew lives together in confined spaces for an extended period, things can become – um, a little brittle. How does Katharsis II’s crew stay sane?

“We typically sail with nine – me and eight crew,” says Koper. “And I know many of your readers will think 100 days together sounds like an eternity. I guess it helps that the crew members are all Polish. And many of them are ‘core’ crew. They’ve been on most of the voyages. So we all know each other very well. Still, everyone welcomes the opportunity for a bit of shore freedom in places like Auckland.”

Katharsis II will spend the New Zealand winter in Auckland while Koper enjoys a sunny break in the Northern Hemisphere’s summer. While here she will enjoy some much-needed TLC – including the fitting of a new boom, courtesy of Southern Spars.

The yacht has a carbon-fibre rig, and soon after completing the Antarctic circumnavigation, just when the crew were celebrating their accomplishment and thinking the worst was behind them, they ran into a series of storms on the way to Hobart. The boom snapped in a crashgybe, forcing the boat to limp the remaining 1,000 nautical miles to Hobart under foresails only – and perversely, in very light winds.

WHAT’S NEXT?

As yet Koper has no firm plans. Though he has previously circumnavigated New Zealand, he has never visited her sub-Antarctic islands – Auckland and Campbell – so that’s one possibility. “These islands are renowned for their birdlife – seeing it would be fantastic.”

But there is another drawcard – back on the other side of the planet, above the Arctic Circle – the north-east passage across the top of Russia.

Of course.

I don’t want to sound pedantic, but just how does the boat’s name fit into this lifestyle? My dictionary’s definition of ‘catharsis’ has zero reference to high-stress sailing in extreme conditions.

“It was my daughter’s suggestion – she thought it was a good name at a particular point in my life. For me, sailing is an invigorating experience and despite the conditions, it always brings an element of peace. It also provides a welcome ‘distance’ from my business – and that’s always relaxing. So the name is kind of appropriate – and even though the English word is spelt with a C, it derives from the Greek word, where it’s spelt with a K.”

But there is also a far more prosaic reason for the name.

“One of my previous yachts was called Kiwi – yes, a New Zealand boat. I bought her in Europe – many years ago – but the seller wanted to keep the name. I know it’s bad luck to change a boat’s name, but I didn’t have a choice. Katharsis was of a sort of compromise – at least the names begin with the same letter.”

A krazy Pole having another katharsis in Kiwiland. Sounds kinda kool.