I once watched a roguish sailing acquaintance of mine throw his delightful Owen Woolley sloop into a hove to position, with jib backed and helm over, while he casually stepped down into his dinghy and rowed over to our boat. Story By Matt Vance.

He proceeded to lean on our rail, order a short rum and drink it while never once looking over his shoulder at his boat sitting faithfully there like a dog tied to a lamppost outside the dairy. Sure, it was five knots and flat seas but you had to admire the courage of the cheeky bastard.

In a short-handed cruising yacht heaving to and getting the boat to sail herself make the difference between a pleasant voyage and exhaustion. One skill makes the boat go while the other makes her stop.

My roguish friend had taught me a powerful lesson on how to stop, which stuck with me. If you could get the boat to look after herself she would outlast even the toughest of your rum-swilling crew. For the rest of that summer, I set out to experiment with the sailor’s art of heaving to in all sorts of conditions.

Heaving to has been around as long as sailing itself and was done often in square-riggers to man the boats or see out a nasty gale. For something with such a rich history it’s surprising that it is not often seen these days, which explains why, to an uninitiated, modern sailor it can look like you can’t sail.

On more than one occasion we have hove to on a day sail aboard Whitney Rose, stopping to have lunch, and been told to “Ease the jib a bit” by a passing boat. I usually take an extra big bite of my sandwich, nod my head and wave my beer in their general direction as a way of not saying anything untoward.

At the risk of sounding like a tacky infomercial, heaving to is one of those multi-use tools in your sailing skill kit. At one end of the scale, it is an excellent way to stop the boat temporarily without all the fuss and mess of anchoring.

It is great for having lunch, a cup of tea and lie down and is superb when your deck monkeys have made a cock-up on the foredeck that needs some time to sort out. Most of all it gives you time to think and if you are at the end of a long voyage without sleep and the leading lights don’t make sense, it might just save your life.

At the other end of the scale heaving to is an effective heavy-weather tactic. There is more advice on surviving storm conditions in a cruising yacht out there than relationship advice. Like relationship advice, it is mostly proffered by those who have no experience.

One thing is certain – most of the time, and for most cruising boats, heaving to will be your best bet. The difference between bashing and crashing along only just in control – and being hove to – is dramatic. Suddenly the boat goes quiet and the conditions lose their sting.

It will take a while playing with the mainsheet, tiller and sail plan to get her to sit comfortably and even then you will sit nervously in the hatch waiting for it to all turn to shit. After a while watching the boat look after herself will fill you with a mix of wonder and gratitude. You will pat the old girl on the cockpit coaming and offer your thanks before slipping below into the quiet sanctuary of the cabin.

Before long you will be baking a batch of scones or reading your way through an impenetrable Tolstoy novel wedged in you bunk while the gale rages on.

When it comes to heaving to, every boat is different. Long keelboats like Whitney Rose heave to well as her heritage is from the nuggetty Bristol Channel pilot cutters. These boats were designed for a pilot and his boy to bash their way out to the Bristol Channel and wait hove to for a sailing ship to turn up at which point the pilot would step aboard the ship and the boy would sail her home.

It required a boat that could sail well and stop well in any weather. The long keel gives a wide sweet spot around the centre of lateral resistance and conversely, a narrow keel on a light-displacement racing hull does the opposite. To heave to on such a hull requires much more finely tuned efforts and, in some cases, even this is not enough.

How to heave to

If you are heaving to for a toilet break, a cup of tea, or a lie down during pleasant weather you will need a full mainsail and some jib. Simply sail hard on the wind and do a long slow tack without releasing the jib sheet.

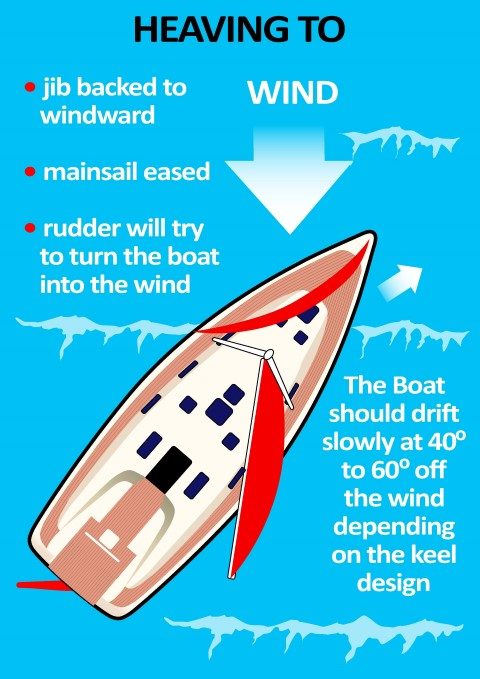

Wait until all way is lost and then put the helm downs if you were going to tack back. In theory, the jib will blow the bow off while the mainsail sheeted in and the rudder will try to head her into the wind.

The boat will hunt around a bit while you try different combinations of jib, helm and mainsheet which, when you’ve got them in balance, will have her sitting around 45o off the wind and slowly going sideways. If you have got it right the keel will have stalled and be laying a slick of turbulent water to windward of you. In light conditions this won’t mean much, but in big seas it will take the sting out of the breaking faces.

Oddly enough the lighter the breeze the harder it is to balance the boat in the hove to position. The most likely culprit is too much foresail pushing the nose off the wind and letting the boat forereach out of her slick. On Whitney Rose, we get rid of the jib for heaving to after about 15 knots and rely entirely on the reefed mainsail or trysail if it is breezy.

Some boats will refuse to heave to. They are more than likely light displacement racing boats. In this storm scenario, you will need a good supply of excellent helmspeople on short rotation watches to keep the boat sailing. On a cruising boat you will most likely not have that luxury. You will be shorthanded, so if you can let the boat do the work you are onto a winning strategy.

It has been years since my roguish friend leaned on the rail while his yacht lay hove to beside ours. I have never had the guts to emulate his feat and now see it for what it was – a simple skill masquerading as an act of supreme confidence designed to bludge rum off passing boats.