Over a 40-year career with his company Heritage Expeditions, Rodney Russ has been to places about as far from civilisation as you can go. Not content with a lie-down and a cup-of-tea kind of retirement, he commissioned a new 24m sail-assisted expedition vessel.

She’s named Strannik. It roughly translates to ‘religious pilgrim’ and if you consider wildlife conservation as religion, she’s been putting this creed to the test – from the Russian Far East to the Tropical Pacific – since her launch last year.

After a lifetime traversing the Southern Ocean, Russ has learned a thing or two about what makes a great expedition vessel. Despite our proximity to some of the most extreme locations on the planet, expedition vessels are rarely seen in this neck of the woods. The need for strength and self-sufficiency precludes most of the market in New Zealand and for this reason Russ’ research took him to American designer George Buehler.

Buehler took the features of the northwestern salmon troller and converted the form into seaworthy, economical long-range cruising motorsailers. They’re affectionately termed ‘diesel ducks’ and almost have a cult following in the 38–45-foot range. Bill Kimley of Sea Horse Marine builds diesel ducks in his Zhuhai shipyard in China’s Guangdong province and turned Buehler’s Strannik concept into reality.

Kimley has a long history of building steel cruising boats and stepped up to the Strannik challenge – the largest of the diesel duck range and the first to be built in full commercial RINA CLASS survey. Australian adventurer and former diesel duck owner Don McIntyre handled the build’s project management.

Construction

The rigorous RINA CLASS standard is for unrestricted worldwide navigation – Strannik is capable of going places well off the beaten track. Construction is more akin to a small ship than any anything else. A 456mm wide steel keel box (filled with concrete) supports 30 x 12mm frames with 8mm steel hull, deck and cabin plating. The flybridge is the only fibreglass part of the vessel (to reduce weight). The hull has full watertight compartments.

The walk-in engine room is an engineer’s dream. Centre stage is the John Deere 6135AFM75 M2 pushing out 425hp @1900rpm via a ZFW 3.43:1 gearbox. It’s so clean and white you could hug it. The engine’s flanked by twin Northern Lights 26kVa generators with automatic battery chargers.

These are supplemented by 2 x 400-watt wind generators and a large solar panel array supplying 24 volts to a 2000Ah battery bank. To starboard of this set-up are two reverse-osmosis desalination plants producing 10,560 litres a day, supplementing the 8,517-litre freshwater tanks.

Further forward is an Alfa Laval fuel-polishing system, to clean up the diesel before distributing it to two 1,800-litre day tanks. That’s a lot to take in and requires the boat reviewer to rest on the stairs and catch his breath before heading up to the main saloon.

Layout

The ship-like construction flows into a layout designed for comfortable, long-duration living. At the substantial transom is a water level swim/fish platform, backed up by stainless outboard fuel tanks and a walk-in lazarette, which contains the steering gear, dive compressors and an imposing spare propeller.

Above are the davits embracing a 4.8m Naiad tender with its 40hp Yamaha. Up the steps from the stern platform is the outdoor dining area which has lashed-in clears for cool or rainy weather.

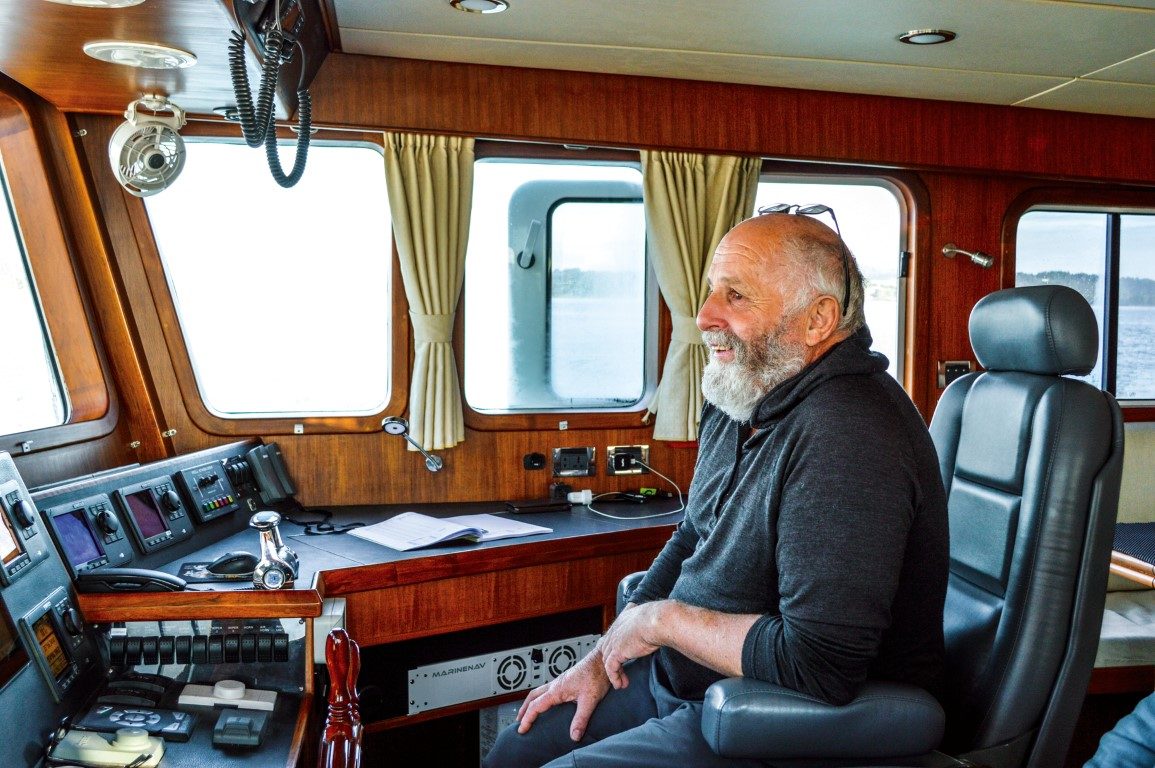

The main saloon has generous room for dining and lounging to port and the excellent galley to starboard features all the comforts of a commercial kitchen. A step up brings you to an impressive bridge dominated by Simrad MFDs and switching needed to run the Naiad computerised gyroscopic active fin stabilisers and the electrical and tankage systems.

It is here that Strannik’s ship-like proportions are felt most keenly – with her large dash and forward-raked, trawler-style windows. There’s a touch of tradition with a timber spoke wheel, though the steering’s mostly handled by the Simrad AP70 auto helm. As per RINA survey requirements there are back-ups for every system. Comfort on the bridge is courtesy of two watchkeepers’ seats, with a U-shaped settee behind for visitors keen to watch the action.

The foredeck has further seating in front of the bridge. The forward end’s dominated by the dual Muir VC 4500 anchor windlasses with 150kg CQR and Bruce anchors on 130m of 14mm chain. This is a ship-sized anchoring system for a vessel clocking in at around 131 tons.

Down from the saloon are two aft double cabins with en suites and a laundry room. Forward of the engine room are four more double cabins with en suites and a couple of crew cabins and heads in the forepeak. The cabins are climate-controlled by a Cruseair reverse-cycle system and all have Wi-Fi and dedicated tablets to access the ship’s book and movie library.

Above the main saloon is the flybridge accessed via steps from the port quarter. The flybridge deck contains an additional helm station, sail controls, ample lounging as an additional tender, crane, kayaks and two chest freezers to carry the food necessary for extended stays in the wilderness.

On the Water

While Strannik’s designed for adventures to far-flung destinations, our voyage for this review is a somewhat more humble trip from the Bay of Islands to the far-flung wilderness of Whangaroa Harbour. The combination of a COVID economy and winter means it’s nearly deserted.

From the Naiad tender sent to pick me up, Strannik quickly identifies herself from all the other boats in the anchorage. Her scale is impressive and her handsome workboat pedigree is apparent. She exudes confidence and a sense of purpose.

The other strong feeling when coming aboard is a sense of home. She is not a marina queen, nor a gentleman’s fancy – she is Russ’ home and you get a feeling that you’re about to embark on one of his world-famous expeditions.

It’s quickly apparent that neither the owner nor the boat are ordinary. Strannik is a small ship rather than a motor-sailer. There’s a sense of space and sturdiness that instills confidence. With school holidays in full swing, there are nine people aboard including four children and the layout seemed to swallow them up without any trouble.

Russ’ expedition experience is manifest throughout. From the bridge layout to the sea-friendly galley she’s built to handle all conditions with style. I was chatting with him on the foredeck as the anchor was coming up and was impressed with the single most decadent thing I have ever seen on a boat – a hot freshwater wash-down for the anchor chain.

“We can make 10,560 litres a day so we tend to use water like you would on land,” he says with a cheeky grin. We were in the unusual situation of the anchor chain being cleaner than the reviewer.

From the bridge, the John Deere is nothing but a faint hum but quickly moves Strannik to her 8 knots cruising speed. “At this speed we’re using 2.5 litres per nautical mile and that gives us a range of 5,000 nautical miles,” says Russ.

It’s a fairly casual comment but with mind-boggling implications. The 15,520-litre diesel tanks have just been filled which should serve the vessel for most of the next year on her proposed doddle around New Zealand and a summer in the Sub Antarctic Islands, Stewart Island and Fiordland.

The day is windless so it’s motor only for the voyage north. The quartering southeast swell would have most boats rolling and cork-screwing but this is easily absorbed by the Naiad stabilizers.

Helming consists of sitting back in the skipper’s chair with a cup of tea and adjusting the Simrad autopilot occasionally. In bad weather, it would beat the hell out of getting wet with the bonus that you can wear carpet slippers rather than sea boots on watch. As with most motor-sailer configurations the rig is small, but as Russ points out: “Any sail area you can get up tends to reflect in the economy rather than speed.”

With a spectacular dolphin welcome into Whangaroa Harbour the crew has plenty of vantage points, with the bow and flybridge being the favourites among the young of heart. There’s enough daylight left for a run ashore before settling into a freshly-caught snapper dinner.

Strannik is a clear case of back to the future for Russ, who started Heritage Expeditions on vessels this size and smaller. In her first year she’s covered 17,500 nautical miles and as Russ says, “she has the toughness to go anywhere, the nimbleness to get into all the out of the way anchorages and the endurance to stay there for a long time.”

Strannik Specifications

loa 23.7m

lwl 22.8m

beam 6.2m

draft 2.47m

net tonnage 131 tonnes

power 425hp John Deere 6135AFM75 M2