Lloyd’s Register – the world’s largest and most respected database for the classification of ships and yachts – is nearly three centuries old. Bizarrely, it all began rather modestly in a London coffee house. Story by Lawrence Schaffler.

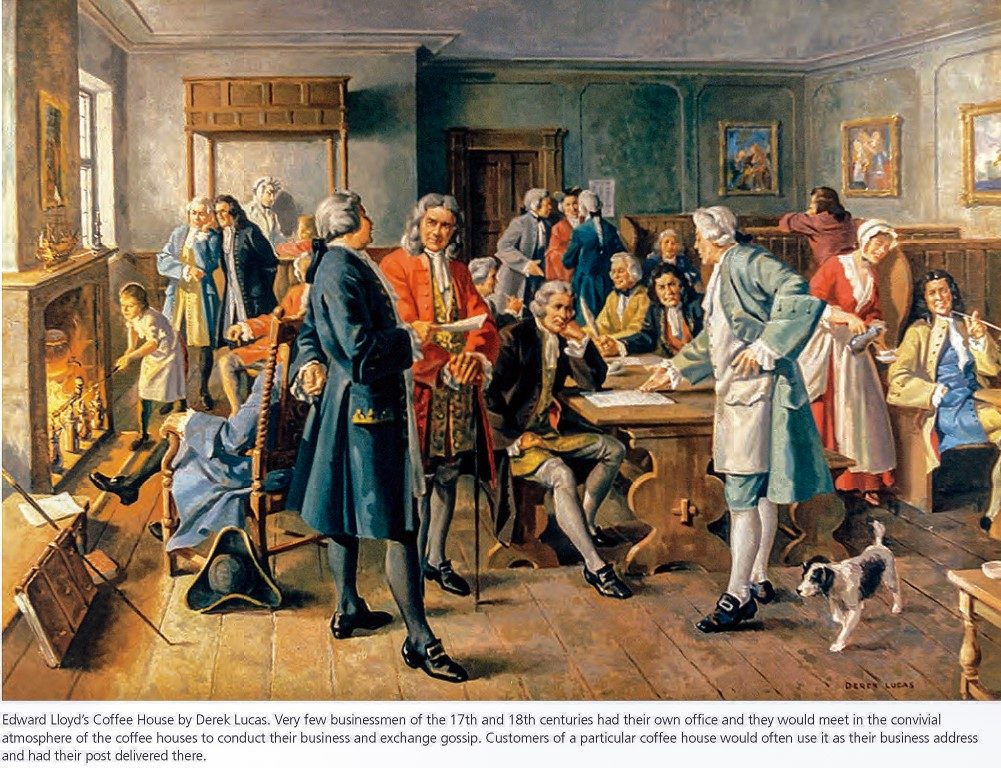

Today, thanks to WiFi and the Internet, conducting business in a café is commonplace. But it’s not a new phenomenon: men were doing similar things in 17th century London when they visited coffee houses to discuss ships and shipping. One of these coffee houses – founded by Edward Lloyd in London’s Tower Street – became the foundation stone for Lloyd’s Register.

Lloyd’s Coffee House – where it all started – is mentioned for the first time in a 1688 issue of the London Gazette, describing a gathering of merchants, underwriters and other players connected to shipping. Coffee was probably the key factor in the venue’s success: everyone remained clear-headed – unlike those opting to conduct business in breweries and taverns.

And Lloyd introduced a useful custom to keep negotiations moving along at a decent lick: a candle was lit at the beginning of an auction – and it ended when the wax melted away. Modern boardrooms might benefit from the same technique.

Lloyd died in 1713 but his café remained a hub of activity – and the timing was perfect: between 1700 and 1750 the maritime industry doubled both in value and volume.

Eventually, in 1760, the coffee house customers founded the Register Society, the world’s first ship classification society. It would evolve into the primary source of information for all those involved in the maritime sector. The Society published the first Register of Ships in 1764 – a tool designed to provide a clear idea of the condition of chartered, owned and insured ships.

But because there were no clearly defined rules or standards at the time, ship classifications were riddled with inconsistencies and this, understandably, led to friction between ship owners and underwriters. In 1774 the frustrated underwriters founded Lloyd’s of London and, in 1799, published their own, alternative register.

This wasn’t a good move. The rivalry drove everyone to the brink of bankruptcy. Eventually commonsense prevailed and in 1834 the two registers amalgamated to form Lloyd’s Register. It began producing a volume (Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping) classifying all ships calling at British ports.

GROWTH AND STANDARDS

The Register received a healthy boost in the 19th century with the technical revolution in shipbuilding. The first steamships appeared – and with them iron hulls – and shortly thereafter, the first propeller-driven ship was classified.

In 1853 a Leith shipbuilder – Thomas Menzies – suggested using a Maltese cross as a symbol of ‘excellence’ for easy classification: today it signifies that a ship and/or its machinery has been built to Lloyd’s Register class. Ship safety and seaworthiness also improved: the first loading recommendations were introduced by the Lloyd’s Register in 1835, more than 40 years before the famous Plimsoll Line was created. These hull marks indicate that a ship has sufficient freeboard and adequate reserve buoyancy.

In 1868 the first overseas offices were established in Holland and Belgium, followed by the appointment of surveyors in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italy, France, the German Reich, Denmark, Norway, Australia and China. By the 1880s LR-classed ships were operating half of the world’s maritime trade.

A YACHT REGISTER

Recreational boating was also incorporated into the classification system. Yachting became popular in 19th century UK – the Brits were fanatical racers and began commissioning ‘extreme’ boats: light and fast, but also fragile and insecure.

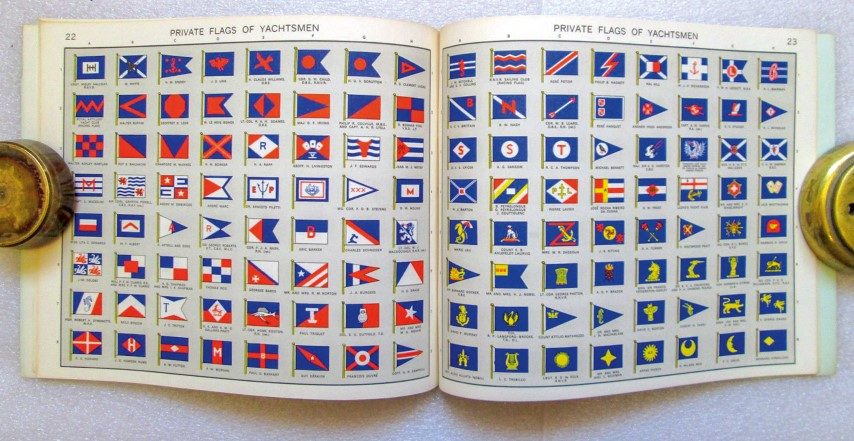

After a few fatal accidents a gentleman named Ben Nicholson proposed the introduction of standards and rules that led to the adoption of the International regulation for the measurement and tonnage of the yachts. In 1878 Lloyd’s Register of Yachts was born.

In the same year it began to publish the now-famous green registers containing yacht data and the rules for their classification. Today these records are a remarkable repository of information about vintage yachts and a primary source of research for anyone into yachting history or restoration.

Editions in the 1960s include data for some 15,000 yachts (both motor and sailboats): technical specs, construction materials, builder, owner, past names, engine, sail number, sail maker, classification and much more.

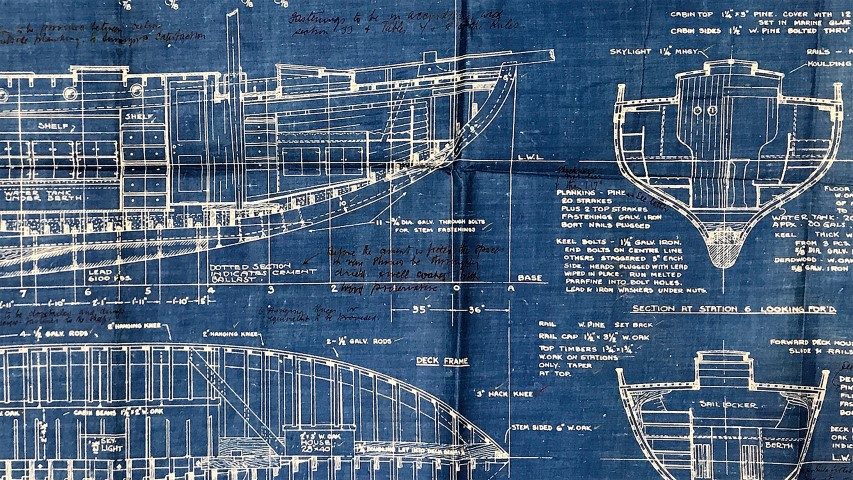

Other sections of the registers were developed and dedicated to shipyards, designers, fleets, yacht clubs. Colour plates showing national flags at sea, owners’ distinctive flags and burgees were also added. And advertisements were introduced.

The annual compilation of this wealth of material – in a pre-digital era when information was sent via snail-mail and patiently typeset for printing – would have been an exhausting task.

The Yacht Register’s success was also boosted by its ‘social’ significance. Owners of unclassed yachts listed in the registers would see their printed name next to that of notables such as Sir Thomas Lipton, Lord Dunraven, the Duke of Cumberland and other peers of the kingdom. In class-conscious England, this visibility carried serious status.

The Society became so important that by the end of the 19th century new London premises were a priority. Land was acquired at the end of Fenchurch Street and architect Thomas Collcutt commissioned to design the new building in the Italian Renaissance architectural style. It became operational in December 1901, soon after the death of Queen Victoria. In 1903 the Register was replicated in North America – with a blue cover – but publication ceased in 1979.

WW1 AND THE GREAT DEPRESSION

During the Great War, thanks to its staff’s professionalism and expertise, Lloyd’s Register was asked to inspect the steel used for non-marine purposes. And in the 1920s and 1930s it was requested to certify both the construction of airplanes and oil storage tanks – this marked the beginning of the organisation’s broader involvement in other industrial sectors.

But the economic crisis that followed the 1929 collapse of the New York Stock Exchange dealt Lloyd’s Register a heavy blow. It had to adapt to a recession that affected both sea trade and shipbuilding. A decade later, the outbreak of WWII saw the headquarters shift to Wokingham and the replacement of almost all male staff with women. Men were enlisted or called to collaborate with the armed forces as consultants involved in the amphibious operations and the removal of wrecks from the ports.

Personnel operating in German-occupied countries experienced even harder times. Some were repatriated, others tried to carry on their business as best as they could, appealing to the independence of the Lloyd’s Register from His Majesty’s government.

REBIRTH

Things were much more favourable after 1945 thanks to the shipbuilding revival, which accelerated the demand for appraisals and consultancies – services already in the company’s DNA. It also became increasingly involved with appraisals in fields such as structural engineering, metallurgy, the energy sector, offshore operations and refrigeration.

Lloyd’s Register changed its name and legal status in 2012. It’s now called Lloyd’s Register Group Limited and is a public limited company with shares owned by Lloyd’s Register Foundation. Today the Group has 7,000 employees worldwide with offices in 78 countries. The historic venue in Fenchurch Street was restored in 1972 and expanded in 2000, when an adjacent glass, steel and concrete complex was inaugurated.

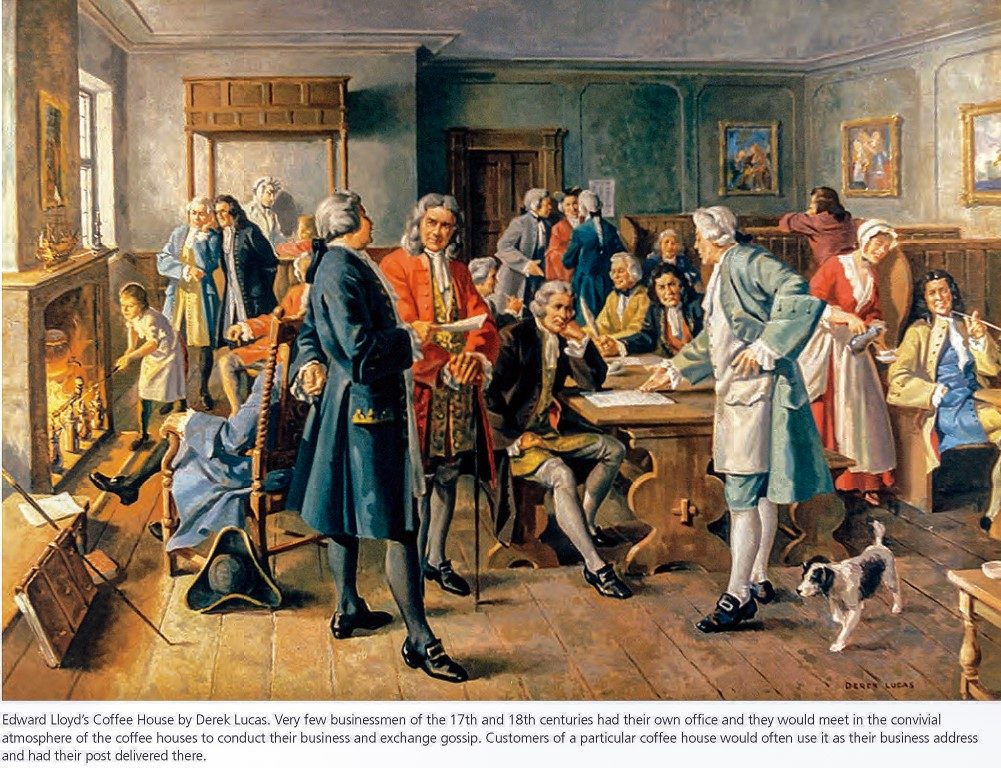

But naval inspectors and technical staff now operate a technological development centre in Southampton. It retains the documents and construction plans of commercial shipping vessels classed by the Lloyd’s Register, as well as the plans of offshore oil drilling rigs and other production sites. Whenever an accident is reported or, more simply, maintenance is needed, plans are required and consulted before a surveyor is sent to the site.

These documents remain the property of the shipping company as long as the ship is in commission and cannot be consulted by anyone else. The plans and documents of historic vessels classed by the company are different: in fact, surviving documents are to be digitised and, eventually, everybody will be able to enjoy the amazing heritage of the Lloyd’s Register from the comfort of their living room.

The writer is indebted to the LR Foundation’s Anne Cowne and Mat Curtis for their assistance.