Lying just south of Sicily and close to the North African coast, the tiny island of Malta’s been pivotal for Mediterranean trade ever since mankind ventured into boating. But its strategic location also triggered plenty of bloody conflicts for possession and control. By Lawrence Schäffler.

Though the arid, sunbaked landscape and barren soil provides little in the way of sustenance, Malta lies in a fortuitous spot at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Sea.

Early seafarers travelling east-west and north-south quickly discovered that the region’s prevailing winds and sea currents could be very helpful for voyaging. At the centre of it all lay Malta, and the island became a convenient stopover. It also became a melting pot for diverse languages, cultures, and religions – a powerful catalyst for the exchange of ideas. Inevitably, it evolved into a major trading hub.

An archipelago comprising three main islands (Malta, Gozo and Comino) with an abundance of natural harbours, it’s situated in a relatively narrow ‘channel’ between Europe and Africa. The region’s imperialists (there were many) soon realised that whoever controlled Malta controlled the Med’s trade routes – which is why the island was used as a military/naval base for so much of its convoluted history.

Numerous occupiers and invaders arrived over the centuries – among them the Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Arabs, Normans, Genovese, the Order of St John, the French and, finally, the British – before Malta finally gained independence in 1964. Many traces of these disparate influences are still visible in the ancient, limestone buildings and the narrow, cobbled streets of the capital city, Valletta – and especially on the city’s bustling Grand Harbour.

While the maritime archaeological record extends back some 3,000 years to the Phoenicians (generally acknowledged as the earliest of the planet’s true bluewater seafarers), all subsequent occupiers left their fingerprints on Malta too, endowing the nation with a rich – though often bloody – heritage.

As the Mediterranean’s economic, political, and religious powers tussled for dominance, Malta served as a battlefield – repeatedly. Three of the most tumultuous events (long, drawn-out ‘sieges’) remain deeply embedded in the Maltese psyche – perhaps because the invaders also attempted to starve the locals into submission.

They were the Ottoman Empire’s Great Siege (ended 1565), Napoleon Bonaparte’s French siege (ended 1800) and the WWll Axis siege that ended in 1942. The latter lasted two years, and with more than 3,000 bombs dropped by Italian and German planes, Malta was all but destroyed. By all accounts the Ottoman Siege was one of the bloodiest events of all time – at least that’s the way Maltese history records it.

Still, through sheer tenacity Malta prevailed and today marks its survival of the three sieges with ‘Victory Day’ every September. As history demonstrates, war and religion are often easy bedfellows and Victory Day also celebrates the Virgin Mary’s birth (despite an underlying Arabic flavour, Malta is predominantly Catholic).

The festivities are particularly famous for the (very loud) fireworks that light up the evening sky – reminiscent, ironically, of WWll’s devastating aerial bombardment.

And speaking of religion…

Knights of Malta

Arguably, the greatest influence on Malta’s maritime heritage was launched in the 1500s with the arrival of the Order of St John (commonly known as the Knights of Malta) – an English religious organisation devoted to caring for the sick and infirm. But in addition to their hospital duties the Knights were astute businessmen and lifted Malta’s fortunes by building a shipyard.

They were also excellent navigators and knew how to handle themselves in battle. They proved vital in resisting the Ottoman Empire’s onslaughts during the 1565 Great Siege. With the Turks repelled, Malta flourished under the Knights, particularly because of the boom in maritime trade.

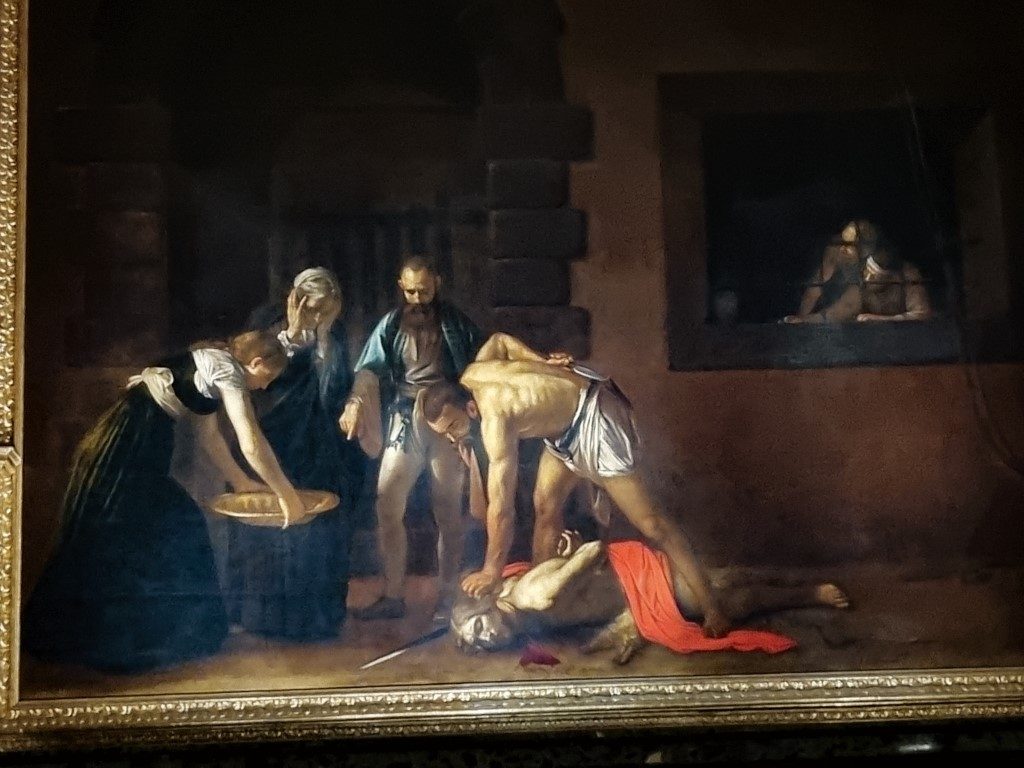

The Knights’ influence permeates so much of the island and is best reflected in Valletta’s St John’s Co-Cathedral. Many of the Knights are buried under the ornate gravestones that make up the edifice’s floor. The cathedral also contains numerous artistic treasures, chief among them the ghoulish painting Beheading of St John the Baptist by the Italian master Caravaggio (1571 – 1610). Measuring 3.7m x 5.2m, it is the largest of Caravaggio’s works.

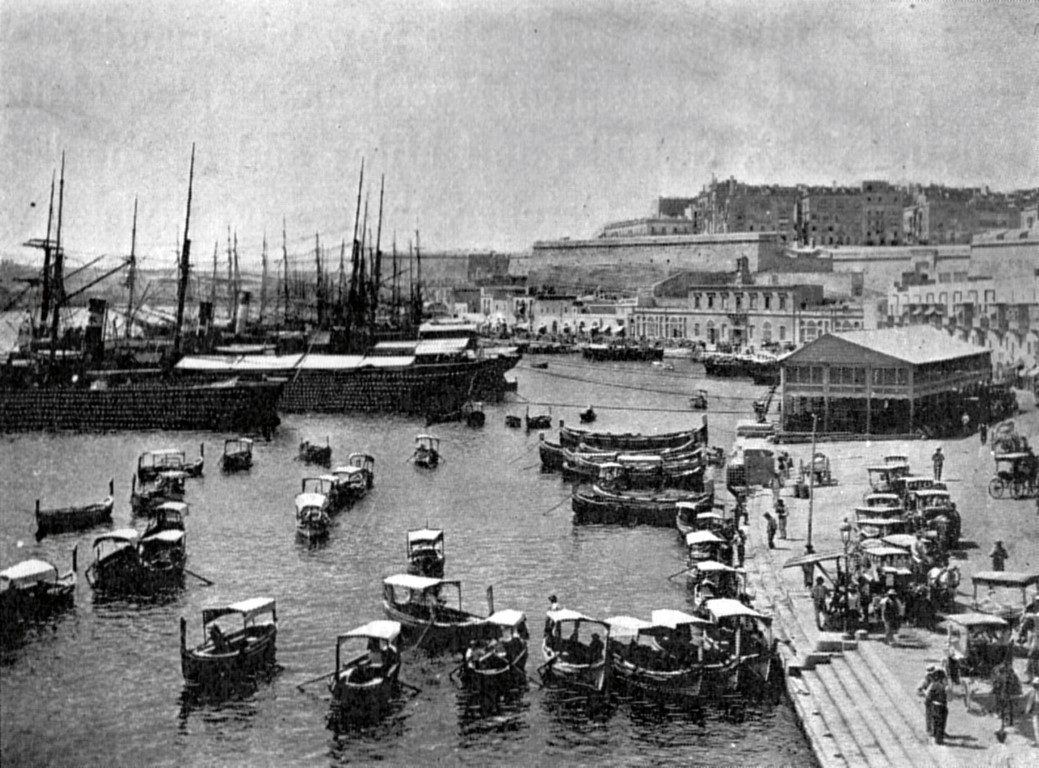

A primary item among the Victory Day celebrations is a boat race on Malta’s magnificent Grand Harbour, hotly contested by two-man rowing crews from villages dotted around the harbour’s perimeter. Their vessel is the dghajsa – a traditional water taxi. Developed in the 17th century these boats remain a Maltese icon, ferrying passengers around Grand Harbour. Oars and rowlocks have been replaced by outboards – less charming but a lot faster.

The vessels’ high stems/sterns are thought to be a nod to Phoenician ship design. Painted in vibrant colours, many also carry the ‘Eye of Horus’ on their bows – crucial for warding off evil spirits. In additional to the Phoenicians, the Eye and its charms was also used by the ancient Greeks and Egyptians.

A good way to gain a sense of Malta’s extensive maritime heritage is to visit its Maritime Museum. Built in the 1840s, it was previously the Royal Naval Bakery supplying visiting British ships with bread. The British used the building for various purposes until they departed – it then evolved into the Museum in 1992.

The collection contains more than 20,000 artifacts covering thousands of years – right back to prehistory. Notable items are a large mid-18th century model of a ship used by the Knights (believed to have been used by the Order’s nautical school), and the world’s biggest Roman anchor (four tons). For more information visit www.heritagemalta.mt/explore/malta-maritime-museum

British rule

When Bonaparte’s troops finally shuffled away from their unsuccessful siege in 1800, the British wasted little time moving in. Malta became a British colony in 1813 – and though the island gained independence in 1964, the British remained until 1979. It proved vital for the Empire’s operations in the Med – particularly during WWII.

Malta was Britain’s only Mediterranean base during the war – it served as a strategic centre for the Allies’ activities in the Mediterranean and North African campaigns, and later, for the Allies’ assault against Germany through southern Europe.

Today, there is plenty of evidence of the British presence – including the traditional red post boxes and the Queen Victoria Gate. One of the most colourful naval traditions is the firing of the noon gun and the pomp and ceremony that surrounds the immaculately maintained Saluting Battery overlooking Grand Harbour.

As with so much of Malta, witnessing the ancient cannon in action carries an eerie sense of stepping back in time.