Why aren’t we doing more to breed and release native fish? A simple question with complicated answers. Alex Stone looks at some of the issues surrounding marine species re-introductions.

Our daughter Zoë is a field research ecologist. She’s currently doing post-doctoral work, monitoring the fortunes of native birds reintroduced to mainland islands.

New Zealand ecologists are considered world-leaders in this type of terrestrial re-introductions. So why can’t we do something similar to help restore our inshore marine habitat? In the Hauraki Gulf, for instance, and other coastal habitats, once keystone species are fast disappearing. Like hapuka and kōura crayfish.

For the last 30 years the total commercial fishing allowable catch for hapuka, unchanged since the early 1990s, has not been caught. Whether this is a result of fishers priority-targeting other species, hapuka proving too elusive to catch, or because hapuka populations have crashed is unknown, says Professor of Marine Science at the University of Auckland, Andrew Jeffs, but the last is the most likely – “We still have no real data on hapuka population dynamics.”

Hapuka were once a dominant inshore reef predator in the Hauraki Gulf. But they are now locally-extinct in the inner Hauraki Gulf, and don’t appear to be returning – even in protected circumstances. In 40 years of diving at Cape RodneyOkakari Point Marine Reserve (Goat Island) near Leigh, Andrew has never seen one.

So why don’t we work to re-locate them to reserve areas?

“The answer is simple,” Nick Shears, another UoA marine science researcher, responds: “It’s because we eat them!” But then he quickly gets serious – “There’s also way more to it than that.”

There are initiatives afoot to breed native fresh- and saltwater species, based mostly on their potential for aquaculture. We’re doing it because we want to keep on eating them!

Things are a little different with shellfish. As Andrew says, “Groups like Revive Our Gulf, The Nature Conservancy and iwi are restoring shellfish because they want the restoration of ecosystem services and the mauri they represent. They are like the early planting NGOs – like Native Forest Action Council – who sold the idea of replanting native forests widely in the community so that it is now seen as the norm.”

So how can aquaculture initiatives help conservation of endangered marine and freshwater species? What are the risks and possible pitfalls? How could this become a good news story?

It’s emblematic perhaps of New Zealand’s freshwater species conservation that the only fish officially protected is already extinct: the upokororo grayling. Last seen in the late 1920s, the species went into terminal decline after the introduction of trout in the 1870s.

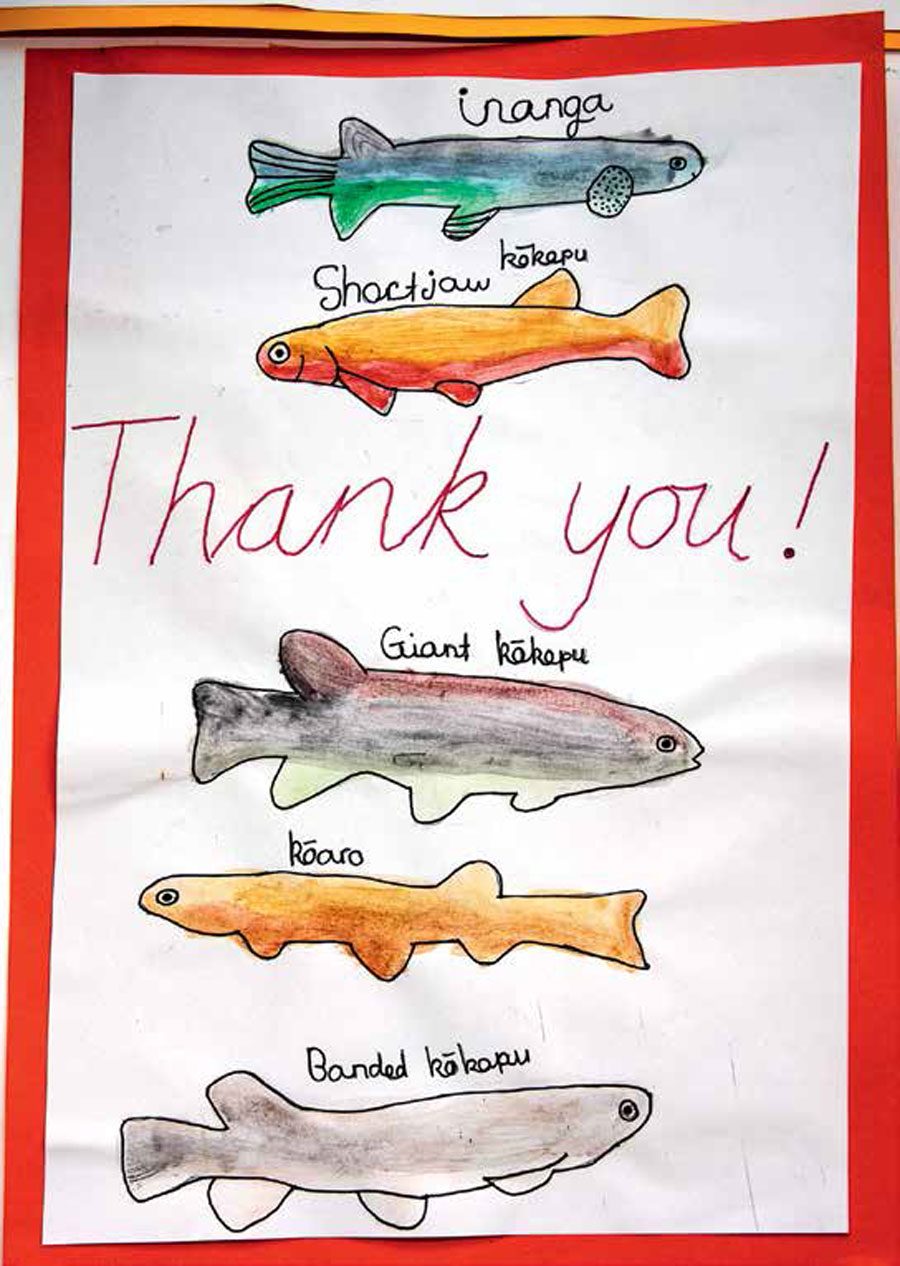

And kōkopu, whose juveniles make up four-fifths of the whitebait run, and that other at-risk native species, tuna longfin eels, are harvested commercially and marketed as Kiwi delicacies. We wouldn’t think of shooting and selling whio/blue duck, say, but it’s okay to exploit these other freshwater-habitat native species!

When I wondered aloud to fish scientists why reintroductions are so much an accepted and regular part of terrestrial conservation, but unheard-of in water, Bruce Hartill of NIWA set me straight: “The terrestrial situation is far, far easier than the marine environment when it comes to conservation. Terrestrial animals mostly raise their offspring, but fish mostly broadcast their eggs, so there is very limited connection between adults and offspring. The ‘parents’ are just adults sharing gametes [eggs and sperm] in a body of water.

“So it’s a completely different situation, with almost no parallels. Enhancement of sessile [organisms fixed in place] shellfish is much easier, though.”

NIWA has an experimental hatchery in Bream Bay, Northland, breeding kingfish and hapuka for aquaculture. But to release them into reserves? “They may not stay,” says Andrew Jeffs. “We know so little about them. There is no academic literature on this subject.”

But in the 50 years that the Goat Island Marine Reserve has been operating, no hapuka have been released there.

And the issue is wider than what a single experiment like that could reveal.

Andrew Jeffs again: “Hapuka are another example of the unfortunate fisheries management regime that is operated in New Zealand. We should just stop fishing them and let the populations recover – they are a key predatory species in coastal areas that we have fished out and are continuing to do so.

“It is different where we have destroyed populations and they are not recovering on their own, then there is an argument for restoration intervention – such as in the case of green-lipped mussels.”

Postive initiatives include projects to restore green-lipped mussel beds in the Firth of Thames area, supported by the University of Auckland, and the NGOs Revive Our Gulf and The Nature Conservancy. Andrew says the mussel beds become critically-important habitat for juvenile fish, especially bottom-feeding species.

This re-stocking is to help the Hauraki Gulf recover from the massive harvesting of mussels, beginning in the early 1900s.

While there have been scattered episodes of fish reintroductions in New Zealand, Andrew says there is currently “no systematic, scientific data-driven programme” to do this more widely.

However, it costs far more to artificially grow fish and then release them than it does to simply allow their natural populations to recover. For instance, only modest costs are associated with signage and buoys at marine reserves. But still, there’s the problem of hapuka not returning to Goat Island.

NIWA scientist Richard O’Driscoll: “I would have reservations/doubts that this [reintroduction] would be successful for hapuka. The question you would need to ask is what is causing the ‘extinction’ of hapuka inshore. Your assumption is that this is due to lack of juveniles ‘recruiting’ into these areas. To be successful, re-introduced juveniles would then need to: remain in the area of re-introduction; survive until they grow through to maturity and reproduce, so their progeny return to the inshore area.

“Given the likelihood of fish movement, and dispersal of eggs, larvae and juveniles [juvenile hapuka are pelagic], I doubt that these criteria would be met.

“I’d suggest that best method to re-establish hapuka inshore would be for there to be a large increase in abundance of existing ‘wild’ natural populations. This would require management intervention [such as reduction in recreational and commercial fishing effort].”

NIWA’s Bruce Hartill: “The main prerequisite for rebuilding inshore hapuku/bass populations would be to constrain commercial and recreational catches to a level that would allow fish to form a critical spawning density. But what, exactly, is that level? Right now, we simply don’t know.”

From Darren Parsons, another NIWA scientist: “The advantages that terrestrial restoration has is that the area being restored won’t also be open to the trees being harvested immediately after planting, and the trees that are planted are capable of reproducing, leading to self-seeding in the localised area after planting. Both of these things are less likely for marine restoration, for different reasons.”

He goes on to volunteer “three critical issues in this debate”: EXPLOITATION: Hapuku do pop up in inshore areas as it is. But, they are pretty vulnerable to capture and fishing is fairly pervasive, so I would guess that individuals that do pop up at the end of their depth range (inshore waters) would likely get removed relatively quickly.

RECRUITMENT: The life cycle of marine species often involves a highly dispersive initial phase, so restoring a population at a specific location may not contribute to recruitment at that same location. It depends on currents and could be dependent on specific habitat relationships that support different life stages [juvenile nursery habitats]. So unfortunately, it’s [generally] more complex than for trees on land.

REBUILDING a fish population to a higher biomass overall is likely to generate more offspring and more of those new offspring are likely to settle on the fringe of their distribution. That, combined with some level of marine protection, may allow those new recruits to remain in those areas.

Last word in this hapuka go-round is from Andrew Forsythe, the Aquaculture manager at NIWA:

“Our objective is to develop these species for commercial farming in New Zealand. We are not engaged in any attempts to augment wild stocks through the release of captive bred fish.”

But still, why hasn’t anyone just tried placing hapuka in the water at Goat Island?

There is an initiative underway to look at returning kōura to the northern shore of Waiheke Island. This is building on research initially commissioned by the Friends of the Hauraki Gulf, as part of its campaign to establish a new marine reserve there.

In 2013, the University of Auckland Underwater Club surveyed 18 sites of what looked like perfect habitat. They found no kōura. In June 2021, the club started replicating this search – and widening it to more sites, co-ordinated by Craig Thorburn, a life-long diver, and now designer of aquariums for a worldwide clientele.

Craig sees this as an “incredible opportunity” to make a controlled study of the effects of the rāhui placed around Waiheke by Ngāti Paoa in 2021. This rāhui, he says, makes Waiheke now effectively “the biggest cray reserve in New Zealand.” But he quickly adds, “It [the rāhui] needs to be for much longer than two years” – especially since larvae spend possibly two years offshore.

Echoing the other scientists’ comments about hapuka, Craig says, “Recruitment is the critical issue. And that may not happen successfully if the cray population remains below a critical mass. If spawning biomass is gone, it [the recovery of the population] needs more than just time.”

Trouble is, we don’t know what that critical mass is. In Craig’s view, this project is a “head start, to learn more about their life-cycle.”

He does point to various successful re-introductions of crayfish in South Australia, where “some quite good home territories for crayfish have been established in dedicated sanctuaries.”

In their initial dives, the divers under Craig’s instructions found tiny numbers of kōura. Intriguingly, there are more of the packhorse species.

And true to his irrepressible form, Craig really does have the last word on marine species re-introductions: “The best thing to do is start.” BNZ