Charts exert a powerful pull for New Zealand sailors. Ever since we’d cruised the trade wind ‘Milk Run’ from Acapulco, Mexico, to Bay of Islands, New Zealand, in 1988 on freelance, our 28-foot Bristol Channel Cutter, Harriet and I longed to return to the South Pacific and our home, New Zealand.

One day in the spring of 2021, while going through a closet full of stuff in our Massachusetts condo, out slid a box of old paper charts from our voyage. I reached into the stack and a large chart of Bora-Bora unfolded itself in my hands. The perfect circle of reef, the lagoon of dazzling blue, clouds streaming like cotton from the island’s volcanic peaks – it was all suddenly real. The South Pacific, and the promise of cruising New Zealand waters, had enchanted us again. We had to go.

THE PLAN

We sketched a plan. From our home port of New Bedford, Massachusetts, in November we’d head to Bermuda, then Puerto Rico, then the Panama Canal, the Galapagos, French Polynesia, the Cook Islands, the Kingdom of Tonga, Fiji, and arrive in New Zealand a year later. About 10,300 nautical miles, most of it downwind in the northeast and southeast trade winds.

OCEAN, our Dolphin 460 catamaran, had recently undergone an extensive refit and was up to the task. But a dark cloud loomed over our plans. Tahiti, for one, was in lockdown, and French Polynesia was closed to yachts. During the 2020 December-to-April crossing season, cruisers had been turned away in mid-Pacific, sent back to Panama or north to Hawaii. We knew that, even with Pfizer vaccines and boosters in our arms and high vaccination rates in many of the islands, our dream could be crushed by the coronavirus.

NEW BEDFORD TO BERMUDA – 635NM

Bermuda, in the middle of thousands of miles of Atlantic, is an old friend – for us and for many US and Kiwi cruisers. During the 13 years we operated our Caribbean child-literacy nonprofit, Hands Across the Sea, we’d called into the island 22 times on our ‘work commute’ from New Bedford to the schools we’d assisted in the Leeward and Windward Islands of the West Indies.

But getting to Bermuda from the US eastern seaboard in the autumn is about as tricky as heading for Fiji from New Zealand. First, we look for the tailwinds of a departing front to launch us off the USA’s continental shelf. Next, we look for things to quieten down for the Gulf Stream, a 60-mile-wide, northeast-setting river in the sea bracketed with 100-or-so miles of eddies and back eddies, a stew of currents which boil up rough seas in contrary or strong winds. Finally, we look for a favourable slant to get us into Bermuda.

Autumn is the time to go – a mid- to late-November weather window for a three- to four-day hop. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has declared the hurricane season is over on November 30, but we view the powerful autumn and early winter gales of December as more likely dangers. We have access to a range of weather-forecast data (we find the weather-routing simulations and updates of PredictWind helpful), but we are not meteorologists. Before our passages we rely on meteorologists at Commanders’ Weather to divine a weather window. They can interpret differing weather models, and we can check in with them midpassage by satphone. On this trip we had an old friend, Captain Bill Truesdale, join us. Bill is a circumnavigator – cool, calm, and able to diagnose and fix anything. With breezy, cold winds aft of the beam, we left New Bedford behind.

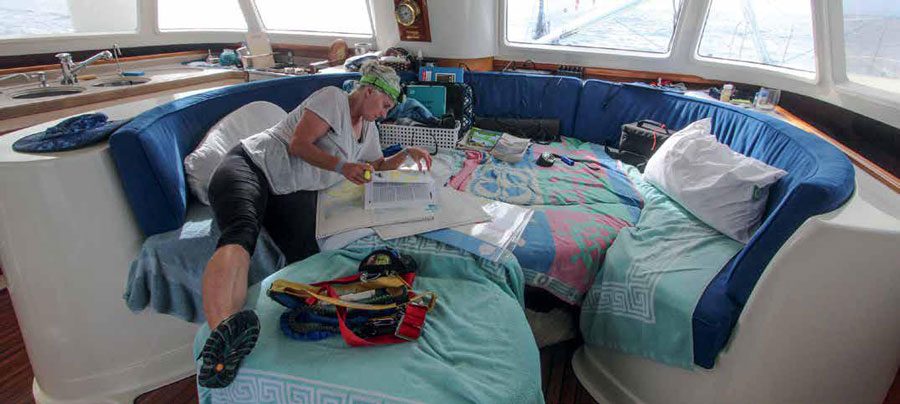

Making great time on Day One! OCEAN is pushing through chunky, confused seas flying a full main and the Code 0. But after dinner there’s a problem: I am seasick. Really seasick. I am able to slither from my bunk to the head to throw up nine times, but that’s all. A three-person team, and one man down. Bill, who rarely gets seasick, is seasick too. But he is soldiering on, standing his watch. Harriet is holding the fort. On we go into the night.

In the morning, a post-mortem. “TL, you’ve been seasick like this three times, and it’s always been at the start of a passage in this chaotic stuff on the continental shelf,” Harriet observes. “You don’t have your sea legs yet.” True. Plus, we’ve been pushing the boat too hard, sailing too fast for the sea state. Plus, I started out the passage on four cups of coffee and not much breakfast; my stomach never had a chance. Lessons learned: ditch the coffee, eat enough non-combustible food to head off the stomach growlies, and take your foot off the gas until we get our sea legs. We knew all this already. But we’d been away from passagemaking for a year and a half, and we’d forgotten.

The final two days into Bermuda are smooth and fast, pulled along by the Code 0. Bermuda, as usual, is a welcoming haven of aquamarine water and pastel-coloured homes, each with a white roof. At that time, the Bermuda Ministry of Health’s Travel Authorisation entry requirements were stringent (submit a negative Covid PCR test immediately before the passage, followed by another PCR test outside the Customs office on arrival), but I didn’t hear any cruisers moaning or second-guessing the health regs. In common with other small islands and ports, Bermuda has only one hospital. Everyone understood that.

BERMUDA TO PUERTO RICO – 905NM

In Bermuda we relaxed for a few days, but we still felt the threat of the US’s winter storms. Commanders’ Weather advised us that in a couple of days a massive system would move south and overspread the island, slamming shut the weather window to Puerto Rico. The choice was leave tomorrow or hunker down for weeks, with uncertain prospects. We quickly wrapped up an engine maintenance project, saw Bill off to the airport, and hoisted a reefed main for Fajardo, Puerto Rico.

Both Harriet and I had been looking forward to getting south, into the tropics and the soft and warm trade winds. It is certainly possible, however, that our hiatus from passagemaking had turned us into softies. Chunky seas, issued from the weather system behind us, bounced us. But we slowed OCEAN down enough to keep our stomachs calm and the off watch rested. Our sail-handling skills – reefing the main in the dark, rolling up the Code 0 in plenty of time before squalls – were a bit ragged, and we revisited our sail-handling teamwork. We’d had no dramas, but we felt more tired than usual. On Day Five the high, bulky profile of Puerto Rico rose in the dawn light.

Embarrassing confession: Despite living in the US for 20 years, Harriet and I had never visited the island. Everything about Puerto Rico surprised us, mostly in a good way. Puerto Rico is larger than we assumed (population: 2.8 million), more developed (malls feature all the US big box stores and franchises), and the people are uniformly welcoming, with an easy sense of humour and pride in their island and culture.

The shores of Puerto Rico are ringed with high-end marinas (we spent two nights at the 1,000-berth Puerto Del Rey Marina, the Caribbean’s largest), luxury housing developments, mom-and-pop marinas (beer, ice, fuel), empty coves and beaches, funky on-the-water settlements tucked behind barrier mangroves, large industrial zones (tank farms, power generation plants, containership ports), wind farms, and perched high above, in the clouds, mountain villages. Areas still show stark damage from the 2017 blasting by hurricanes Maria and Irma. English speakers are fewer outside the city centres, but folks are ready to help. They even listen patiently to our rusty Spanish.

ln 10 days we speed-cruised a variety of Puerto Rico attractions, from the islands of the Spanish Virgins (Isla de Culebra and Isla de Vieques) to the sheltered south coast of the main island. Puerto Rico may lack the US Virgin Islands’ gin-clear waters that provoke irrational exuberance in cruisers, but nature preserves have kept Puerto Rico’s cruising grounds in good shape. Puerto Rico has lots of hidey-hole mangrove anchorages, plus some bioluminescent (phosphorescent) coves. Puerto Ricans are very social, and the water is their playground – on holidays, anchorages are crowded with raft-ups of sportfishing boats and packs of jet-skiers.

Now it was time to move on. We were not really on a schedule, but the South Pacific and New Zealand was calling. Whether a self-manufactured myth, or embroidered memories from three decades ago, or the prospect of real adventure, the mighty Pacific occupied major space in our minds. For one thing, the Pacific is rich with centuries of Spanish, Dutch, and British discovery, and we looked forward to sailing in the wake of these history makers. But before that, more history awaited. BNZ