The Arctic Circle, at 66 degrees 34 minutes north, was well astern and the compass card, becoming unreliable at these latitudes, danced around Magnetic North.

Meeting the last of Norway’s whale hunters at home

Even eyesight wasn’t too dependable. Here, in the ‘leads’ – a winding waterway through islands and fjords on Norway’s northern coast, snow-peaked granite mountains floated metres above the horizon and passing ferries seemed to float on air.

This, I learned later, was Fata Morgana, an optical illusion caused by refraction through the cold band of air at sea level and named after the Arthurian sorceress, Morgan le Fay, who is said to have used it to lure sailors to their deaths.

A week or so out of the Shetland Islands, we were bound for Bodo through some of the most scenic waterways in the world, aiming to clear Norwegian customs and then press on north to Spitzbergen.

Dressed in heavy Line-7 PVC smocks, woollen balaclavas and boots, we picked our way up the fjord to Bodo through a fleet of pleasure boats peopled by women in bikinis and T-shirted men wearing shorts. We’d arrived on the first warm day of summer.

But customs clearance was elusive. The customs and immigration officials were based at the airport and not keen on coming into town so, after perhaps a week of futile phone calls, we headed 58nm northwest to Svolvaer, the main town of the breathtakingly beautiful Lofoten Islands.

All night we reached briskly across Vestfjorden, though a fairytale landscape of snow-draped mountains. The sun stayed up all night to illuminate the shoreline and splashes of seawater stung any exposed skin as Elkouba charged onwards.

Winters here are long and dark and the mountains plummet straight into the sea, leaving little room for coastal farming or industry.

In the morning we motored into Svolvaer and tied up to the municipal wharf in the middle of town. Colourful gingerbread houses trailed chimney smoke and, entranced, we walked the back streets.

Then I spotted a flock of crows nests, mounted on wooden masts behind a handful of weatherboard houses.

“Whalers,” I said, “let’s go and have a look”.

Down a narrow walkway between two houses we came onto a wooden wharf with three doughty wooden whalers tied to it. A man stood behind the harpoon gun mounted on the fo’csle of the nearest one, a small boy held in his arms. There was a loud report from the gun and Saah pushed the shutter on her camera.

The man turned around warily. “Greenpeace?” he sighed, and rolled his eyes.

“No,” I replied, “we just like boats and were admiring yours.” “Ahhh,” he responded, “come aboard, come board.”

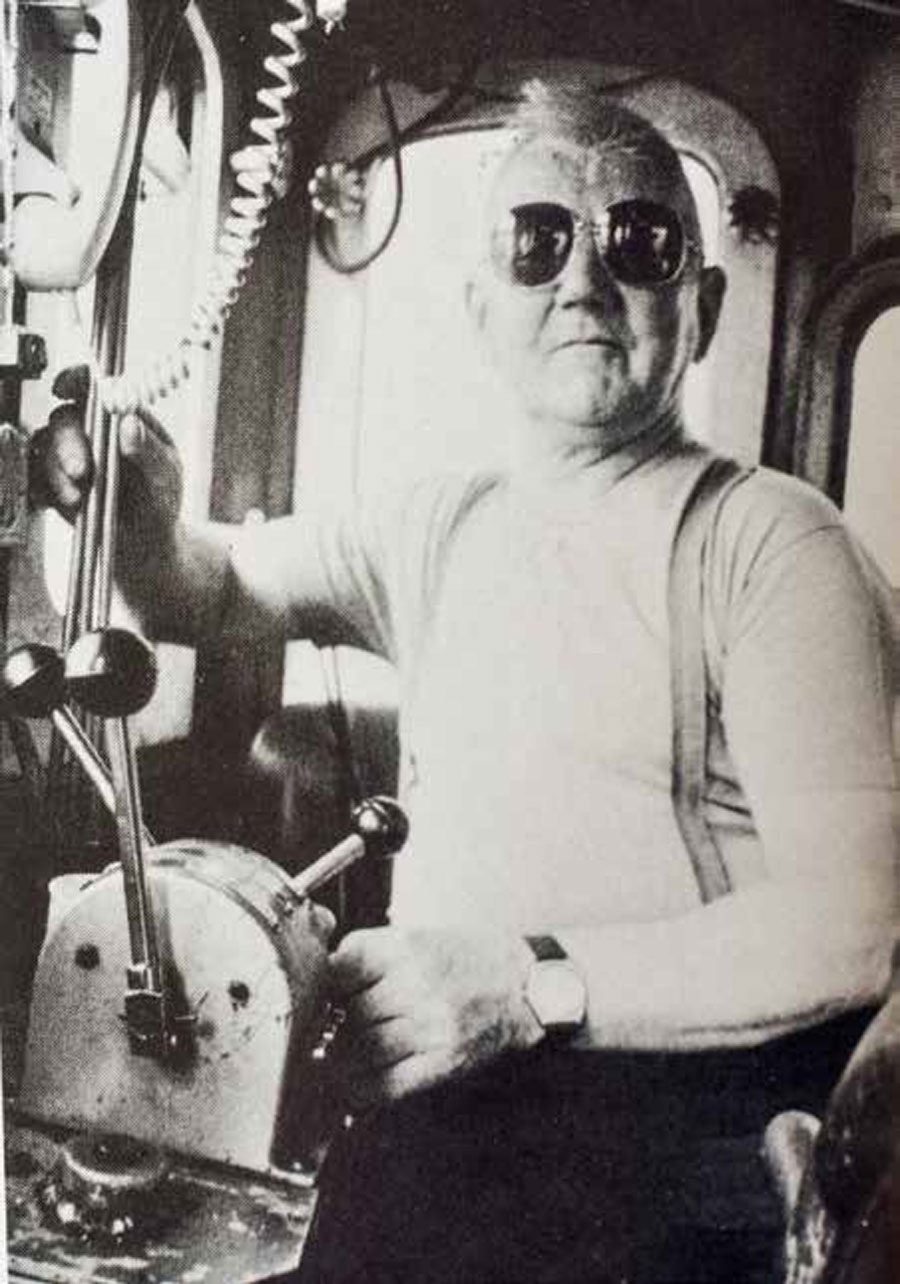

And so we embarked on a tour of Kromhout, a typical Lofoten minke whale chaser. Every summer kvalskipper (whaling skipper) Ernest Dahl took her up to the edge of the Arctic pack ice to harpoon minke whales which are processed on board for the local market.

Built of 50mm-thick Baltic pine fastened to beefy oak frames with big galvanised boat nails, Kromhout had gangways from the wheelhouse to the harpoon guns forward and aft.

“The minke are so slow… if you miss with the forward gun, you can walk to the wheelhouse, spin the boat around, and try with the aft gun,” he said.

About 575 whales were taken in 2021 and skipper Dahl, in a 53-year career starting at 12 years old, says he has personally killed 3,500.

“This gun,” he patted the purposeful grey harpoon gun, “was invented by Svend Foy, a Norwegian. We use 50mm harpoons for minke whale or 90mm for fin and sei whales – bigger species.” The harpoon head is designed to explode inside the whale and kill it immediately, but if it doesn’t, the whale is despatched with rifle shots to the head. It is then winched on board for processing. The blubber is rendered down to make oil and the meat is consumed locally in Tromso, or exported to Japan.

Belowdecks the accommodation is warm and homely and a big GM diesel is bolted into an engine room that is as spotless as a hotel dining room. “We steam to the ice every year to chase whales,” he explained, “so we need lots of horsepower.”

He settles into the wooden chair at the wheel, like someone pulling on a favourite overcoat.

“And where are you from?” he asks. “We came by yacht – from New Zealand,” I say.

“Aahh, New Zealand,” he made a fist of his right hand and thumped his chest with it. “David Lange – strong man.”

And later he added, “You like my father; ‘Sea Rover’ Dahl.” His father, Ragnvald, joined the Norwegian whaling fleet at age 14 and steamed to South Georgia as deck boy in a whale chaser, around the edge of the Antarctic ice pack to refuel at Bluff. Then, with its harvest of dead whales in tow, back to South Georgia and home to Norway.

“Come, come,” and ushered us into the wooden house about 15 paces away over the wharf. Over cake and coffee, we discussed whales and whalemen, life on Lofoten and the long, dark days of local winters when snow falls down to sea level and storm force winds shriek down from the ice pack. He was well-versed in International Whaling Commission (IWC) politics and noted that New Zealand had voted for a ban on whale hunting.

“But you have sheep and little lambs – and you eat them,” he smiled, “what difference is it? We have whales, that’s all.”

“The scientists say that there are this or that number of minke whales – but they don’t come out with us to see. Our whales are like your sheep – my family have hunted whales since Viking times – we don’t kill them all – we need them for the next generations… and to feed the people.”

Eventually, full of strong Norwegian coffee and sweet cake, we walked back to the boat, dropped the lines and motored around to take skipper Dahl’s invitation and raft up to Kromhout.

“Next year the whale hunt is banned – so we will not be going anywhere.”

He had never been on a yacht before and was intrigued by Elkouba, our 12m steel cutter.

For my part, I was fascinated by Kromhout’s nuggety construction, built to nudge her way through brash ice and make a living from doing hard and dirty work in very rough conditions.

For four days we sat beside the whale chaser in the serene waters of the fjord. I helped skipper Dahl with work on Kromhout and he helped me with Elkouba and at nights we dined with the Dahl family and other whalers.

Otherwise we strolled the docks to look at boats. The pleasure boats were mostly plastic production craft, but the commercial boats – salmon carriers, whale chasers and fishing boats – were mostly strongly-built wooden boats, well-kept and shapely.

Skipper Dahl’s mother, Olga (93) cooked the dark red and lean whale meat or fiskeboller (fish balls) which are the local dietary staples. I wondered about the life this dignified old lady, who always seemed to have a grandchild on her lap, had lived – waiting for her men to return from the sea, Antarctic and Arctic.

Skipper Dahl’s two brothers, Arnold and Oddmund, are also whale hunters; their chasers Svolvaering and the oddly-named Charley are berthed further up the fjord. More grandchildren are in training.

Skipper Dahl and I spent hours poring over charts of Spitzbergen. He had drawn tidy little anchor graphics at the best anchorages, marked the areas of the strongest current flows and little swirls were pencilled in to mark where wind funnels and katabatic gusts were most likely. It was a priceless education in arctic navigation.

“Take them… take them…” he slid the charts across the table, “next year there is no more whale hunting – it has been banned – so these are no use to me anymore.”

In fact Norway eventually defied the IWC ban and began whaling again, but by then technology had expanded to provide GPS and chart-plotters.

I didn’t like to take the charts – it was like endorsing the downfall of a tradition, of a way of life. But on the other hand, I would think of the whalemen, superb seamen, every time I used them.

Friends in the Shetland Islands had recommended taking duty-free whisky to Norway where tax and duty have made liquor prohibitively expensive. I took a bottle from our stock and slipped it into Kromhout’s wheelhouse before we took our mooring lines aboard and slipped out of the fjord.

The wind was light and we ghosted northwards, boggling at the stunning vistas around us.

Then we noticed the whale chaser leave the fjord and alter course to head our way. With a big bone in her mouth, she forged towards us, then settled back to an idle and held station about a metre astern.

Skipper Dahl stepped out of the wheelhouse and waved the whisky. “Is too much,” he roared. A young boy ran forward and handed over a 30cm square slab of meat.

We slowly pulled away from Kromhout until there was enough space for the little wooden whaleship to wheel away and head for home.

We had no fridge on board but the meat kept for a week or so in the cold steel bilges. Sliced very thinly and fried with onions, it made a nutritious and tasty dinner.

In Tromso, a white van like a Mr Whippy with extras, regularly parked on the wharf with Hvalbuf (whale beef) painted on it. Housewives arrived on a regular basis, bringing bags to carry the family dinner.

And, in a way, I thought, Skipper Dahl was right. We do eat sheep. BNZ