There’s more than one way to rig a sailing cat. The two-mast biplane rig is a seldom-used alternative that offers many advantages over standard catamaran sail plans, as the Bay of Islands vessel Cool Change demonstrates. Words Alex Stone, photos Lesley Stone.

Imagine a yacht that can go to windward in a storm under bare poles. One that never heels beyond four degrees, is easily beach-able, and does so often. A large cruising yacht handled by two people, able to sail at 15-20 knots and regularly clock off 200-nautical-mile blue-water days, with a wardrobe of only two fully-battened sails. No loose-footed sails, so no flogging, ever. A boat that requires no maintenance to standing rigging, where you can hoist and drop sails at any angle to the wind, no rounding up necessary.

These are the advantages of Cool Change. To gain these benefits, some lateral thinking – and its practical application – is required.

The majority of cruising sailboats are monohulls – those sailors who have opted for fast, modern cruising catamarans have already escaped the conventional. But the vast majority of cruising sailboats – monohull or multihull – have the same rig. The Bermudan sloop.

There must be significant advantages in this, right? Well, not necessarily…

For any cruising yacht, resale value is important. A conventional design makes it easier to on-sell your asset and the predominance of the Bermudan sloop rig reflects this market reality. It’s common because it’s common. Or to put it less bluntly, it’s popular because it’s popular. But…

A catamaran’s wide beam offers an advantage not often fully utilised by yacht designers. It allows for a wider staying base, or two masts, one in each hull. This offers alternatives to the usual Bermudan sloop, some with singular advantages.

The development of modern cruising cats began only 50 years ago, despite Western seafarers who encountered Pacific oceangoing catamarans already acknowledging their superior speed in the 16th century.

Which segues us neatly into the alternative catamaran rig chosen by Don and Marilyn Logan for Cool Change: the biplane rig. With the advent of modern composites technology, the biplane is a seriously viable alternative to the standard, stayed Bermudan sloop.

The biplane rig typically sports two unstayed masts of equal height, one in each hull directly opposite one another. It has many advantages.

The first is that the centreline mast of almost all cat designs requires engineering add-ons to make the whole structure more rigid. The downward force of the mast in the middle of a centre beam must either be counteracted by a sturdy box construction, or a dolphin striker in smaller cats. A seagull striker counters the upward pressure of forestay loading on the front beam.

Both dolphin and seagull strikers require strong cables to run over them, and equally strong anchor points in each hull. More wires, more complication, and more things to fail under stress.

The biplane rig eliminates the need for centreline strengthening, seagull and dolphin strikers. Each mast is keel-stepped. This requires solid mast steps and reinforcing on deck around the mast gates, but that’s it – no extra wires and no loading across large moments of force.

“Won’t one sail blanket the other?” people ask. Well, no. Any experienced sailor will know that when approaching an exact beam reach, cats (and light/fast monohulls) should be steered to bring the apparent wind forward. A win-win airflow is created – the faster you go, the more wind you’ll get accelerating into the breeze.

Cool Change running goosewinged before the wind. A square sail can be rigged between the masts for more speed, but Don and Marilyn reckon she’s fast enough without one.

Cool Change running goosewinged before the wind. A square sail can be rigged between the masts for more speed, but Don and Marilyn reckon she’s fast enough without one.

So, no, you don’t want to sail on an exact beam reach. And for fine reaching, or close-hauled, the two sails of the biplane rig work to create an efficient slot.

The biplane rig was effectively demonstrated at the Weymouth Speed Trials in the 1980s, with the ‘skewed catamaran’ Crossbow II. Its leeward hull and rig were further forward – optimised for the starboard tack of the course – but this wasn’t necessary. Crossbow II managed 36 knots, a world record for years.

The biplane rig took a reputational knock with the demise of the giant catamaran Team Phillips. It was commissioned in 1999 by Pete Goss to win The Race, a no-holds-barred circumnavigation challenge. At 36.66m long, 21.34m wide and 41.15m high, this monster cat was biting off more than the technology of the time could chew. Team Phillips broke up at sea twice and was abandoned mid-Atlantic in 2000 during a freak storm with 70-knot winds and 10m waves. But this was no fault of the rig.

Cool Change has a large and functional galley ideal for charter work or extended offshore cruising.

Cool Change has a large and functional galley ideal for charter work or extended offshore cruising.

Off the wind or dead downwind, the biplane rig offers goosewinging and/or an efficient square sail between the masts, but Don and Marilyn found it a handful for just the two of them. The boat is quick enough anyway.

Other advantages? No foresails that flog. A minimal sail wardrobe. Tacking without adjusting sails. Flat work platforms at the base of each mast. Multiple reefing options. And unparalleled visibility from a central helm.

Based in the Bay of Islands, Cool Change is the most successful of New Zealand’s biplane-rigged cats. It’s ironic that most of Don and Marilyn’s charter guests are unaware they’re being taken out in such an iconoclastic boat. All they see is Don and Marilyn getting underway with no fuss. Other sailors usually see Cool Change’s stern. She’s remarkably quick. In these pictures Cool Change is doing 9 knots in about 6-8 knots of true wind speed.

Flat spaces below the masts and the ability to raise or drop the the sail at any time are among the advantages of the biplane rig.

Flat spaces below the masts and the ability to raise or drop the the sail at any time are among the advantages of the biplane rig.

Cool Change was designed by Derek Kelsall as a conventional cat. But during the seven-year self-build in Opua, Don and Marilyn became sold on the biplane rig. So Kelsall modified the design scantlings for the two keel-stepped masts and re-visited the sail area calculations. Turned out Cool Change could safely carry 30% more sail area, which explains her speed in moderate airs.

Things then went high-tech when in 2005 Don and Marilyn received an innovation development grant from the government to build the biggest free-standing carbon fibre wing masts in the country. After a feasibility study by Chris Mitchell, a Team New Zealand America’s Cup engineer, with final calculations by Pete Lawson, they teamed up with Innovation Lamination, based at Katikati. The secret was to build with epoxy resin infusion, reducing weight without sacrificing strength.

Don reckons he over-specified the strength of the masts. Standing 20m above the deck, they were designed to flex only 1m sideways under full rig load in 35 knots, with a big safety factor. Now Don says he could have gone for 1m of flex at 25 knots (you can always reef), for 20% less weight. No matter. The masts have proved themselves in all conditions, including voyages to the Pacific Islands.

Marilyn at the helm of Cool Change.

The masts themselves are Cool Change’s storm sails; Don and Marilyn have logged respectable speeds going upwind under bare poles. There’s no conventional rig that will top that.

Wing masts are known for ‘sailing and tacking’ a boat at anchor. With a biplane, this is fixed by securing the masts facing each other, cancelling their wont to go sailing on their own.

During our sail aboard Cool Change, the masts automatically tacked smoothly and silently, as the sails filled on each new tack. The angle of the masts to the sail entry can be adjusted with a yoke system – Don doesn’t adjust this much, but it is more efficient to over-rotate the masts on a reach, creating a deeper overall foil shape.

Cool Change’s sails are visibly flat. This is because the fore-aft dimension of the wing mast itself is part of the chord of the sail. The extra wide booms allow for more space between the lazyjacks, making it easier to hoist the sails.

Rudders and other under-hull appendages can be retracted to park the yacht on a beach.

The really big advantage of Cool Change’s biplane rig is that you can drop the sails at any angle going downwind. No need to round up. Don simply lets the sheets go until the sail itself is feathered, pointing directly ahead if necessary, and up or down comes the sail. The unusual technique has led to confused callers on the VHF radio asking whether Cool Change is coming or going!

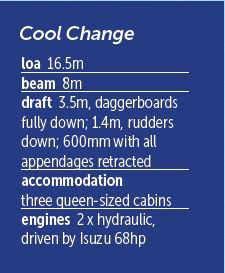

There are other noteworthy aspects of Cool Change. She can be beached easily – Don and Marilyn do this often. The daggerboards, which draw 3.5m, can retract completely beside hull-protecting, shallow keelsons. The rudders kick up and both motors retract fully too. Naturally they have bottom plates below the propellers, to achieve a flush, smooth hull for sailing.

The propellers are driven by hydraulic motors, which are actually in the bulbs at the bottom of the shafts. These hydraulic motors are driven by 68hp marinised Isuzu diesels. This is an advantage cruising the Pacific – Isuzu diesel engines are common, so there’s always someone who can fix them. With 900W of solar panels, Cool Change does not need a genset.

An extra-ordinary boat indeed! BNZ

FIRST COUSIN, ONCE REMOVED BY TECHNOLOGY

FIRST COUSIN, ONCE REMOVED BY TECHNOLOGY

The Logans came from Ponui Island in the Hauraki Gulf near Auckland, where the family has farmed for generations (and developed a unique breed of donkey!). So naturally, they also knew of local yacht designer Bernard Rhodes and his well-travelled biplane-rigged cat, Flying Carpet, on neighbouring Waiheke Island.

Bernard built Flying Carpet in 1984-1989 (considerably pre-dating Phillips), with a more low-tech approach. Her hulls are strip-planked macrocarpa felled and milled and seasoned by Bernard. Flying Carpet’s D-shaped section masts are also wooden – strip-planked Douglas fir – with footholds for a ladder cut in the aft face. Because they are flexible up top, they also reduce the shock loading catamaran rigs are subject to.

A further innovation with Flying Carpet is her wrap-around two-ply sails and wishbone booms.

Flying Carpet has proven herself with many mighty voyages in the Pacific, at one stage taking Bernard, his wife Yachiyo and their young boys Andrew and Ken on an extended cruise to Japan. The travels of Flying Carpet won a Yachting NZ Cruising Award for a most meritorious cruise.

Kelsall also designed the biplane-rigged cat FastKat49 – a 49ft pod cat with twin rotating masts, last seen in the Hervey Bay region in Queensland, Australia in 2018. Unusually, it has a supporting beam linking the masts at three-quarter height.