There are books, and then there are dangerous books, writes Matt Vance. The dangerous ones are the ones that spark something in you that cannot be put out; they stick to your life and shape something of you.

At the age of 13, Robin’s father Lyle sold his home and business and took his family on a cruise through the Pacific on their 35-foot ketch. They returned to Honolulu, but Robin’s spirit remained in the South Seas and not on his schoolwork.

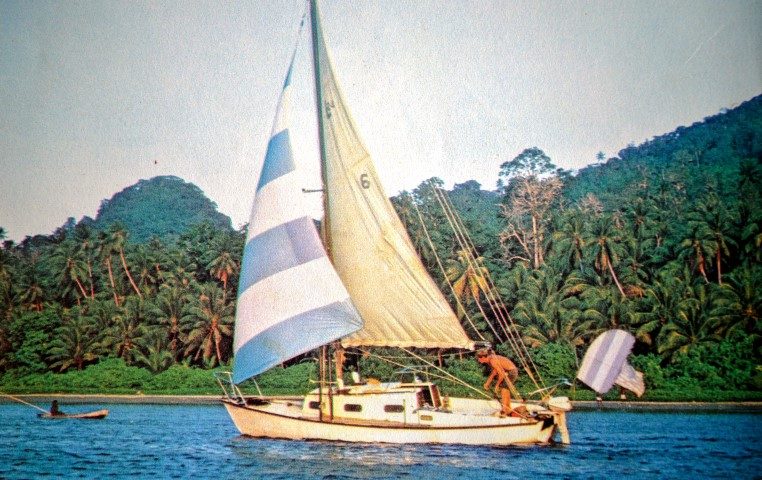

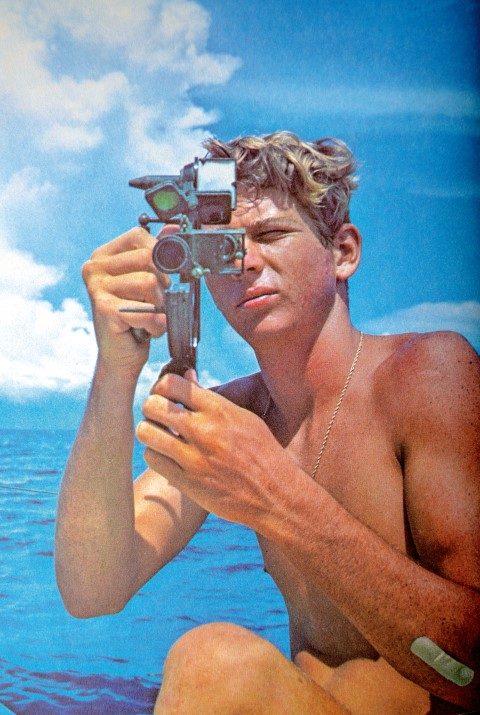

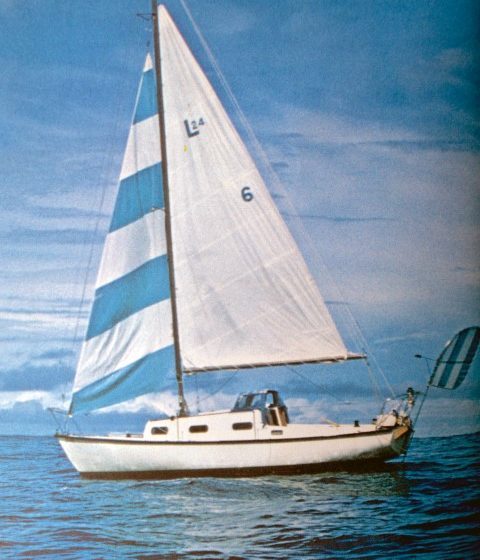

After attempting to run away to sea in a converted ship’s lifeboat caulked with chewing gum, Lyle agreed to buy Robin a Lapworth 24 and fit her out for an offshore voyage. “I figured if I didn’t help him to do it right, he’d do it on his own in a leaky boat,” said Lyle with a degree of parental wisdom unusual for the time.

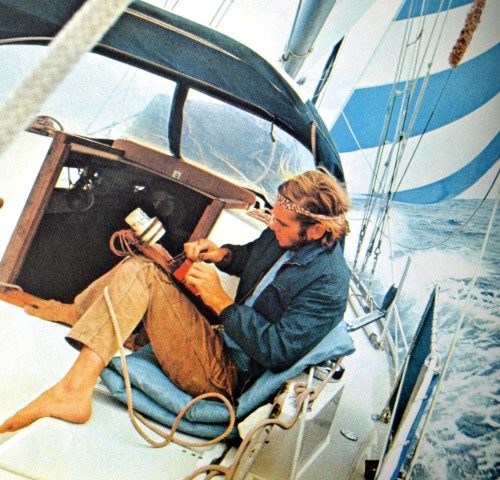

At its heart, Robin’s voyage is still an amazing feat for one so young. He had the usual collection of gales, calms, dismastings and even met the love of his life, Patti Ratterree, in Fiji.

While modern teenage circumnavigators are obsessed with speed and breaking records, Robin sailed at a saner pace with the luxury of being able to stop along the way and experience the world he was sailing around.

Underneath all the nice photographs and the wonder of a boy exploring the world by yacht, there is a darker tale that is equally as epic as the superficial one. While the children’s book never mentions it, the adult versions of the story – Dove and the later Home is the Sailor – detail the account of a kid put under a lot of pressure by his father and his sponsors.

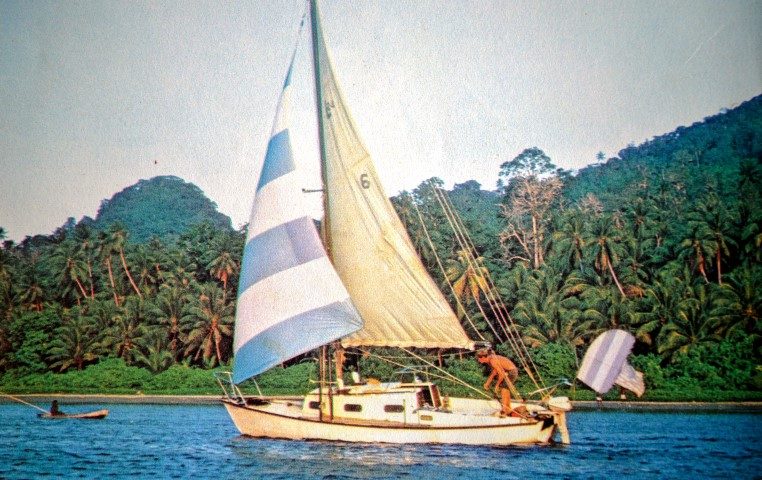

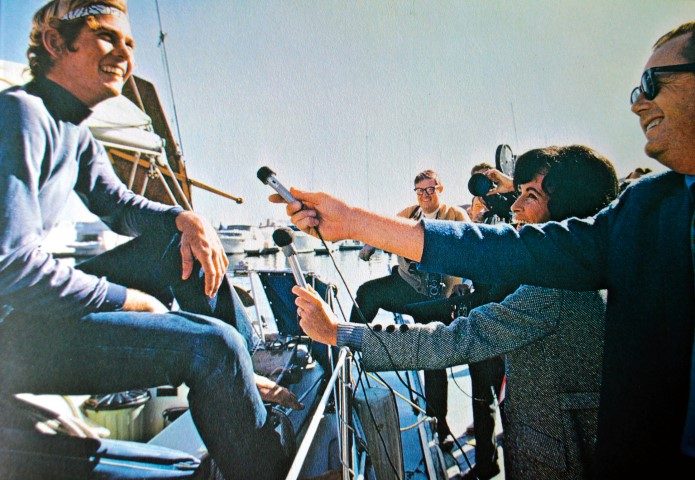

Not far into his journey across the Pacific, National Geographic magazine became interested in Robin’s journey. It carried the story of his voyage in Dove for three years, and it became one of the magazine’s most popular series of articles ever.

Robin and Dove had an all-American photogenic charm and his adventurous life, as portrayed in the magazine, struck a chord in a nation that was undergoing the ructions of the Vietnam war.

The popularity that resulted in his coverage by National Geographic was something that Robin was never quite comfortable with. The artificial poses and the scripting of his story by the magazine were something he came to resent.

Lyle kept reminding him that the sponsorship of the magazine was paying for a large chunk of his voyage, which only served to widen the growing rift between them.

After he completed his five-year solo circumnavigation Robin and Patti were offered all the trappings of urban life, a scholarship to Stanford University and a Ford Maverick.

For a kid who had dropped out of school and escaped to sea, Robin was woefully under-prepared for life back on land. He developed a deep depression, which overran him with all the attendant issues of alcohol and drug addiction.

To his immense credit Robin was able to climb out of these depths with the aid of Patti and their newfound Christian faith. They built a log cabin in Kalispell, Montana, surviving their first winter and a badly-acted movie about his adventures, which came out in 1974. They still live there to this day and have raised a young family and delight in their anonymity.

Robin was no author – all three of the books about his story and the aftermath were shadow written by American writer Derek Gill. Yet, as a trilogy they recall an epic tale of growing up, falling over and growing up again.

At 10 years old all I was interested in was the sailing, the simple purpose of a boy who wanted to see the world by boat. It is still the most dangerous book in my library.

I get it out once in a while and I handle it very carefully. I keep it there because it kindles my childhood dreams. I keep it there to fend off the worst that life on land can throw at me.