Last month’s article featured Norman’s ultimately successful effort to locate Divecat, his 12m aluminium catamaran lost in 43m of water in the Firth of Thames, and his ingenious plan for lifting her. This issue, the salvage effort gets underway.

Of course, nothing ever happens quite to plan or on time, so on our lifting day it took far longer than anticipated to fit the long ropes and the first series of bags, just to get her rising off the bottom. Fighting current and exhaustion, we finally managed to get her floating but only about three metres off the sea bottom. We then drifted and dragged her just over a nautical mile towards the Coromandel before the tide began to ebb and she started snagging.

So, we put her down on the bottom again in 40m of water, releasing most of the surface lift bags and leaving the straps and submerged bags in place. While it was disappointing, I was also very happy – my lift bag design had proved itself up to the task and I now had a good idea of how many bags were required to get her up off the bottom. (Seven, as it turned out.)

It was a few weeks before wind and tide were again favourable, and this time we were much more efficient. The combination of the straps and bags already in place, and a crew with experience at preparing and passing the bags down to the divers, meant we got her floating quickly. Not long after that, we got her close enough to the surface for those on the tow boat to be able to see her outline. It was surreal to see an 8-tonne boat suspended in midwater, covered in marine growth and with her stainless-steel propellers glinting in the sunlight.

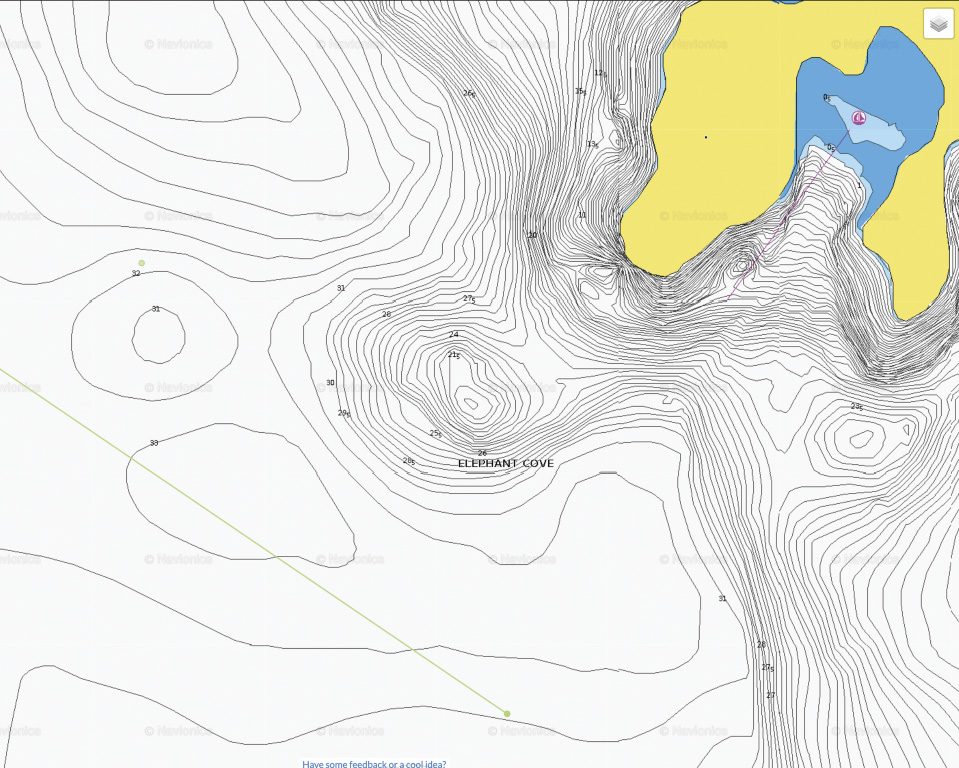

We made sure she was secure with plenty of redundant bags at the surface supporting her weight and attached a new tow rope. This time we got a full six hours of towing time, and I was relieved when she started dragging the bottom in 17m of water just outside Elephant Cove. We released most of the surface bags again and she settled back down on the bottom.

This marked the end of stage one – the longest and most dangerous part of the recovery was now over. At this point I could confidently start to plan what I would do once she was out the water again.

A couple of trips out to Elephant Cove were next on the cards, preparing Divecat for the final lift. Cyclone Cody hit in the middle of this, so my first trip out was to check that the submerged lift bags were still in place. In the process I discovered we had inadvertently set her down onto her starboard side, so organised another trip to deploy more bags to lift her stern, straighten her up, and then set her down upright again. We also did more work on clearing extraneous ropes and some more of that net from the outside of the hull.

It was now time for the final part of the plan. We needed to float her up to the surface and then get her as high out of the water as possible. The ideal would have been to get her to float at deck level, but I realised that was completely unrealistic. At a minimum, I needed about half of the wheelhouse cabin’s sides to be clear of the water, although the tidal range on the final lift day would determine the actual height needed.

Multiple water pumps were purchased and configured, safety boats were arranged, and a couple of friends called in to help with the lift. The tides were right and weather conditions near perfect when a small flotilla set out from Auckland in early April.

We started by again lifting her stern-first, then fitted additional straps tightly under the bow to level her hull. Further complications ensued, including those caused by the remnants of that bloody net that were still obstructing parts of the boat. By the time we got her floating level and just below the surface, we were out of time for the tide. Frustratingly, the only option was to pull her in to even shallower water and put her down yet again, this time horizontally and in just seven metres of water.

Yet another cyclone threatened, and with autumn’s unsettled weather now approaching, it looked like a long delay was on the cards. Luckily the cyclone’s path shifted offshore and – miraculously – the first two days of the Easter weekend looked like being perfect. With most of my previous crew away for the long weekend and a few of the lift bag straps needing repair, it was a hectic week trying to pull everything together.

In the end, I had three other divers volunteer to come along for an overnight adventure and we headed to Elephant Cove one last time. No flotilla this time – just one boat. However, we did have an audience, with eight other boaties choosing the bay as their overnight anchorage. Little did they know their sleep would be disturbed!

As it turned out, the tide times were even better for us than they had been the previous week. The tidal range had also increased to 2.1m, and high tide was at 6:30pm so we had the whole day to get her to the surface.

In fact, we needed every minute of that time, as well as the extra tidal range. After six hours of work and just an hour short of high tide, we had her roof sticking just above the water, but rather lower than I had hoped. I was worried we would not get her high enough. Luckily a frantic effort in the last hour, inflating several bags between the hulls and fitting bags right inside her cabin saw her roof rise about half a metre above the surface. Not nearly as high as I thought we needed, but it was as good as we could get.

We moved her to the shallows by means of a pulley and rope that we had earlier attached to a huge rock on shore. The dive boat motored outwards pulling that rope which resulted in Divecat moving inshore. Once she was touching the bottom we anchored and pulled everything tight. Now we had to wait, and it was some very tired divers who tucked into dinner.

Around 10:30pm a couple of us transferred ourselves and our pumping equipment onto Divecat, which now had the water level down to her gunwale. Still two hours until low tide and I needed the level to drop another half a metre – it was going to be close!

Eventually, just after midnight, it had dropped just far enough for us to start pumping the forward compartments. The rattle of high-volume petrol pumps reverberated around the cliffs of the cove and no doubt did not make us any friends with the other boaties trying to sleep.

The efficiency of these pumps is amazing, although the water pressure from the outlet was so high that it tended to shift the entire pump sideways. Once we had made a significant difference in the water level in the first compartment, we moved the petrol pump to the next one and dropped a high-volume 12-volt bilge pump into the first to take care of the remaining water. At the same time, I hammered rubber bungs into any original through-hull openings I could find. And so, we worked our way through all six compartments, progressively lowering the water level in each.

Once again it was touch and go and we probably only beat the rapidly incoming tide by about 10 minutes. Just after 1:30am we felt Divecat starting to float again, and by 2:00am I knew we had succeeded. Emotions started to set in, but there was still much to do, so I could not yet reflect on the enormity of what we had achieved. We rigged a bilge pump in every compartment to automatically take care of any further water ingress, and finally retired to the dive boat for a few hours’ sleep.

I was up well before dawn and back on board, checking that she was still floating (yes!) and then going through all the compartments looking for leaks. Nothing! She was not taking on any water, and although sitting pretty low in her starboard bow area, that was caused by the weight of accumulated silt and water-logged interior furnishings. It was good enough!

After several cups of coffee and a good breakfast, we spent a couple of hours preparing Divecat for the tow home. Luckily her anchor winch was still solid and well attached to the deck, so that was our tow rope anchoring point. We started the slow journey home with a 45m-long tow rope to tow her across water that was 43m deep (just in case!) and we kept two people on board in wetsuits and lifejackets, and in constant VHF radio contact with one another, in case of any issues.

Across the Firth of Thames, we held our speed at just four knots, but once in sheltered (and shallower) water around the bottom end of Waiheke Island we shortened the tow rope and managed to pick the speed up to six knots. At this point, I succumbed to waves of emotion as

I realised we were finally going to be successful. More than two years of effort, tens of thousands of dollars spent and more than 30 boat trips later, she was coming home! Much blood, sweat and tears had been shed in the intervening time, and more were shed that day.

Once I pulled myself together again, I called the marina to organise an emergency lift. Just after 5pm we pulled her alongside the wharf at Half Moon Bay Marina. Job done!

When they lifted her, we discovered she was carrying nearly four tonnes of sludge, silt, marine growth and absorbed water, which explained her low position in the bow. Over the ensuing days we removed four full skip bins of ruined joinery and furnishings, and eight large wheelie bins of pure sludge. Much more work still to do, but the underlying hull is in remarkably good condition. Now the saga of her rebuild begins.