Apart from those in know, architect/designer Gary Underwood flies under the radar. But over the last 40 years he’s designed many fascinating and innovative boats, often for those on limited budgets. Here’s the story of a man who loves his boats, by John Macfarlane.

Underwood was born in London during the dark days of 1942 when Germany and her Axis partners seemed unbeatable. After the war ended the family emigrated to New Zealand and settled in Wellington.

Inspired by the dinghies sailing out of Worser Bay, Underwood’s first boat was P Class #7, a gunter-rigger which he stripped back and re-painted. Showing an early interest in cruising, he sailed his P to Kapiti Island. Because he told no one he was going, his parents organising a search party.

By 1960 he had joined the RNZNVR and was seriously considering yacht design as a career. His father sought advice from Christchurch yacht designer Eric Cox, who said as there was no money in it, better that Underwood get a real job and keep boat design as a hobby.

So Underwood moved to Auckland for three years to gain a Diploma in Architecture. Besides getting married, during those years he owned the mullet boats Sun and Lady Ruia. A few years later the couple had three children and he was working for architect Nyall Coleman designing churches.

Seeking change, in 1970 he got a job designing houses for the Fijian Housing Authority. It was in Fiji that he bought his first real cruising yacht, the 10.6m Chilean-built Terral. The dream of sailing oceans remained paramount, so after gaining offshore navigation experience on George Kelsall’s 14.9m schooner Lady Sterling, Underwood sailed Terral to New Zealand, back to Fiji, and on to Vanuatu, New Caledonia and Brisbane.

In Brisbane (1974) he swapped Terral for the damaged 17m gaff ketch Utiekah III, which had been built by the Wilson Bros in Hobart in 1927. Built in Huon pine and displacing 47 tons, Utiekah III had lost her keel and rudder during a grounding on the Great Barrier Reef.

While Underwood located her rudder, he couldn’t find her keel. So he fitted a temporary rudder, filled the saloon with 60-litre drums of diesel and motored Utiekah III from Brisbane to Whangarei via Lord Howe Island.

He spent the next 12 months restoring her at Jackson’s slipway in the Bay of Islands, including re-fitting her rudder and installing a new keel to his own design built in concrete, steel reinforcing rods and cast-iron weights.

He helped found the Tall Ships Regatta in 1975 and raced Utiekah III in the inaugural event. Following a suggestion from the visiting Tasmanian yacht Saona, he sailed Utiekah III to Hobart. By now Underwood had a new partner, Robyn Lewis, and they discovered the 47ha Huon Island was up for sale.

As part of a complicated deal, they sold Utiekah III and bought the island and the sailing cray boat Casilda. The couple lived on the island for two years while they rebuilt the original house and had a child together, all funded by cray fishing in the engineless Casilda.

But Underwood got the urge to go sailing again so they sold the island and Casilda and bought Gudgeon, a John Hannadesigned 9m Tahitian ketch, with a new rig designed by Alan Payne. After sailing her from Brisbane to Hobart, Underwood sailed to Fiji and then to the BOI for the 1980 Tall Ships race.

He then did another Pacific cruise in Gudgeon, eventually arriving in the Solomon Islands. There, at Taviulo village on Malaita Island, he met a group of local boatbuilders and, impressed by their workmanship, asked them to build him a new timber yacht.

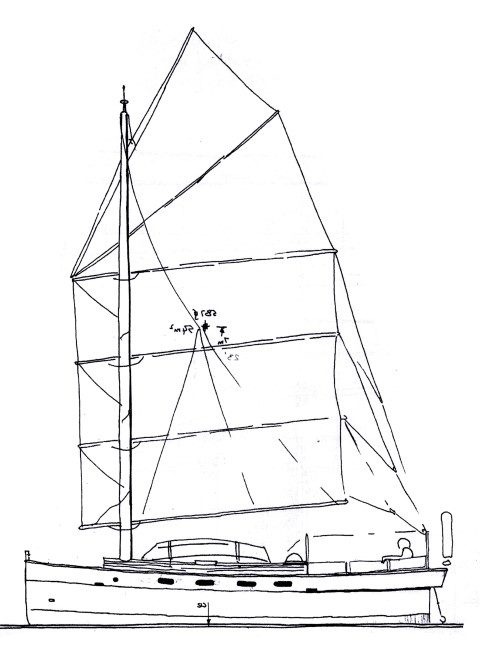

Wanting a long, lean and shallow yacht for a trade winds circumnavigation, Underwood turned to L Francis Herreshoff’s last design, #107, an 11.6m leeboard ketch. While he used Herreshoff’s hull lines and single skin carvel construction, he added bulwarks, an additional 200mm to the keel and installed free-standing masts with sprit-rigged sails.

He also eliminated the lee-boards because a deep draft’s unnecessary for a trade winds circumnavigation. The slightly deeper keel gave a loaded draft of only 1.14m, which proved sufficient to beat to windward in flat water. As Underwood puts it, “Why would you dig a 1.8m hole across the Indian Ocean?” Built over 12 months in Vitex coffasus (a Pacific hardwood), the engineless Alice Alakwe cost NZ$27,000 and became Underwood and his new partner Beryl Sampson’s home for seven years. Their circumnavigation took the classic trade winds route – Australia, Indian Ocean, South Africa, Brazil, West Indies, Rhode Island,

USA, Azores, UK, Spain, Portugal, West Indies (again) Panama, Galapagos, Gambier Islands, French Polynesia, Tonga, Fiji and then home to New Zealand.

In all they sailed Alice Alakwe 56,000nm, with a best day’s run of 208nm. As an aside, Underwood completed a yacht design course while in Maine USA, which proved more than useful later.

In 1990, back in New Zealand, Underwood and Sampson chose something completely different for their next yacht – a 16m trimaran inspired by Chris White’s Juniper. Interestingly, the late Digby Taylor, who headed two New Zealand Whitbread campaigns, helped Underwood with the CAD design of what became S.W.I.S.H. Instead of White’s constant camber construction method, Underwood used strip-planked cedar and glass and he completed S.W.I.S.H. in only 18 months.

But they didn’t enjoy the powerful S.W.I.S.H, finding the large trimaran scary in blustery conditions when her 700mm-deep wing mast proved excessively powerful. “When she was good she was great, but when she was bad it was horrible.” So S.W.I.S.H. was sold to the South Island, but sadly her new owner wrecked her on rocks off Torrent Bay in the Abel Tasman Park.

Then in the early 1990s Underwood designed a 10m, junk-rigged cruiser for Keith Levy, who’d abandoned his yacht Sofia during the infamous 1994 Pacific storm while voyaging to Tonga. Built in double-chine plywood, Shoestring’s raised topsides gave an interior accommodation equal to many 12m yachts, while her expansive decks allowed plenty of room for a decent dinghy. Shoestring was launched for under $10,000 in 1996 and inspired several sister yachts, including one built in steel.

After a stint in Auckland as yacht broker during which time they restored the 1937 Fred Lidgard-built 8.5m Taioma, Underwood and Sampson moved back to Whangarei and started building their next yacht, a 12m version of Shoestring, called the Bootstrap.

Built in only 18 months from timber and plywood and launched for under $40,000, Ava Aakwe’s huge interior was big enough for the couple to use as a floating home. Rigged as a gaff cutter with lee boards, she was powered by a lowrevving Lister diesel.

The couple sold Ava Alakwe to fund the building of a house in Whangarei and bought a boatshed in the town basin. With a partner Nigel Clarke, in 2005 Underwood bought the Jim Young-designed-and-built 16m canting keeler Fiery Cross. Launched in 1958, Fiery Cross was the first canting keeler ever built, and while Underwood appreciated the innovative concept, he was less impressed with its shape. “That keel was a terrible shape, we had to re-fair it with cedar.”

He replaced the boat’s original Ford 10 petrol engine with an 18hp Kubota. He also fitted one of the original bronze Aries wind vane self-steering units, which are highly-prized these days.

Then, after losing a $20,000 inheritance through financial company shenanigans, Underwood decided he’d rather keep his money under his own control, and bought an ex-fishing boat, the 14m, 22-ton Mason Bay.

Originally built in 1956 by Nelson boatbuilders Curnow and Wilton and launched as San Guiseppe, Mason Bay went through a number of different owners during her commercial fishing career. She was located in Bluff and early in 2010 Underwood motored her to Whangarei for a 20-month restoration and pleasure craft conversion. He had considerable help throughout from shipwright Marcus Raimon.

These days, Underwood spends most of his time living aboard Mason Bay in the BOI, returning to the couple’s flat in Whangarei every few weeks to spend time with Sampson. He’s still designing boats, selling plans and has recently self-published a design book with over 70 designs. While a number of these are complete, many others are concept sketches and ideas.

There’s a massive variety; long lean schooners, fast trade wind cruisers, motor-sailers, launches, houseboats, catamarans, trimarans, day-sailers, an OSTAR racer, a three-part dinghy that’s a tender as well as lifeboat and much more.

Despite the variety there are some common traits. Underwood abhors the Swiss army knife approach to boat design – he likes to start from square one: how will the boat actually be used? “The closer you can pin down that purpose, the better it will be solved.”

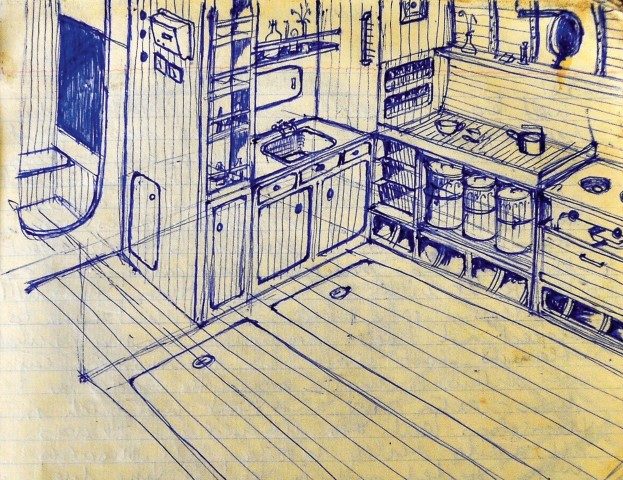

Most of his boats are designed to be built from plywood – “laminated cellular fibre” he calls it – which is strong, light, easily worked and, provided it’s coated and/or sheathed in epoxy, long lasting.

He believes full headroom is over-rated. Naturally it’s needed in the working areas, but there’s no need for it over bunks or seats. “I quite like deck beams right across the hull, you can lift them up or drop them down. They’re great structurally and don’t leak.”

Raised beams in the accommodation areas add hugely to the feeling of space downstairs, while dropping them in the lower areas provide bulwarks for on-deck security. Alice Alakwe was built this way and it worked really well.

Underwood hates liferafts and inflatables – “deflatables” he calls them – better to invest in a proper dinghy that can be used every day. In the event of an emergency this can double as a lifeboat and be sailed to a shipping lane, rather than waiting around hoping to be found.

Skin fittings are another Underwood no-no, each one costs a 1% speed loss as well as being another maintenance item. Wind vane self-steering is essential for cruising, which he prefers to address with a stern-hung rudder with an external flap driven by a wind vane – simple, reliable and fixable at sea. He snorts in disgust at those who use electronic autopilots – they’re usually the first thing to fail on passage and require professional repair.

So, there you have it. If you’re a left-field sort of boatie, or even a bit of boating lunatic, and/or if your pockets aren’t too deep, a chat with Underwood could well kick-start a boating dream. And if you’re clever enough to dream it, you’re certainly clever enough to build it.