It’s a grim fact that the current Covid-19 epidemic is just the latest in the waves of pandemics that have swept through humanity regularly since recorded time. We forget quickly!

Over 9,000 New Zealanders died in eight weeks in the pandemic known as the ‘Spanish Flu’, a virus that arrived in a relatively mild form by ship from overseas in September 1918. Despite its name, it had nothing to do with Spain.

This form of influenza possibly originated in Kansas in the United States, flourished in the US Army’s camps from late 1917 and went with the doughboys to France. It spread rapidly across Europe, affecting both sets of opposing armies across the trenches in France. The Spanish Flu was a strong factor in the rapid decline of the armies of the Germans and their allies which led to the Armistice and cessation of hostilities on 11th November 1918.

A second wave of this influenza, probably a mutation of the first virus, and in a much more virulent form, arrived here in October 1918 on steamers from America and Europe with cases on board, notably Niagara, Tahiti, Ionic, Paparoa and Makura and the hospital ship Marama bringing servicemen home.

Niagara arrived in Auckland from Vancouver on October 12. Calls by Auckland’s mayor for quarantining the disembarking passengers were refused, it was said, because two senior politicians were on board – the Prime Minister,

Bill Massey, and Sir Joseph Ward, co-leader of the wartime coalition government.

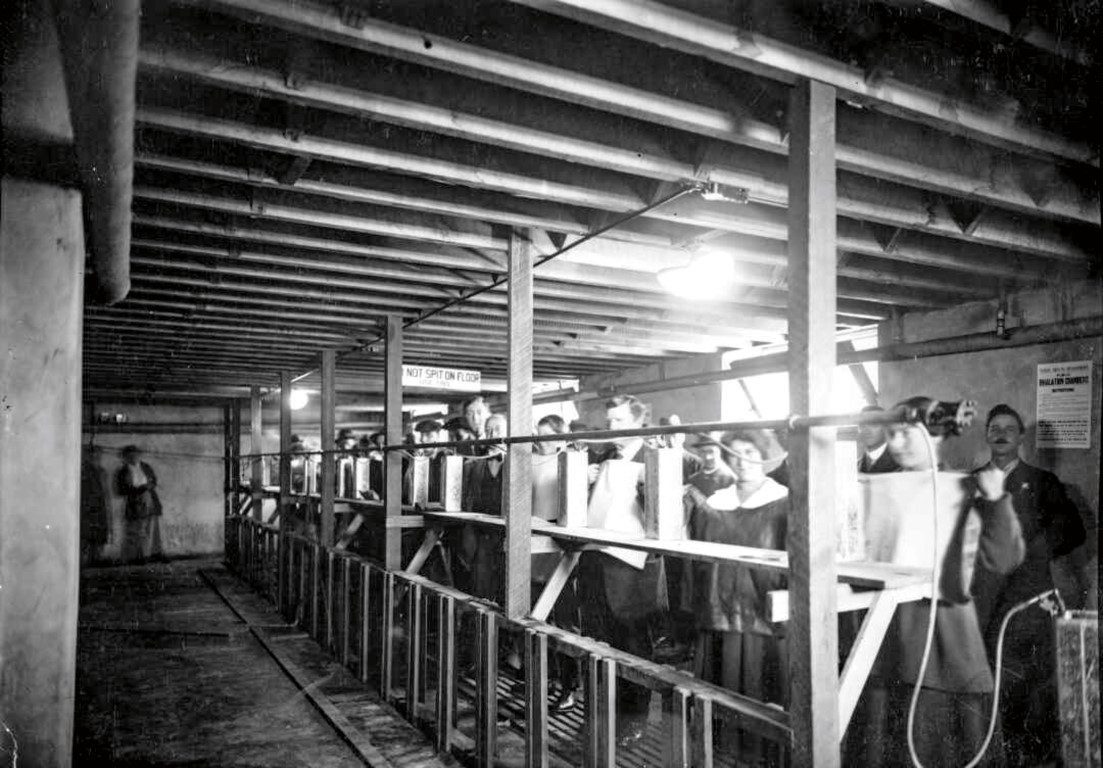

They had spent five months in England conducting official business and visiting Kiwi troops. Influenza was not then a notifiable disease. However, all passengers and crew were “disinfected” on coming ashore.

These steamers, passenger and merchant vessels, troop ships and hospital ships had acted as fertile breeding grounds for infection during their passages to New Zealand, in the same manner as 2020’s cruise ships and US Navy ships.

Unlike Covid-19, the 1918 virus seemed to target healthy young adults. Death often occurred within three days of symptoms appearing. A large number of soldiers returning from overseas in these ships died aboard or, while being demobbed, in New Zealand’s Army camps, particularly at Featherston and Trentham. Many people, including soldiers, suffered depression from the virus and committed suicide to avoid the horrors of the influenza death.

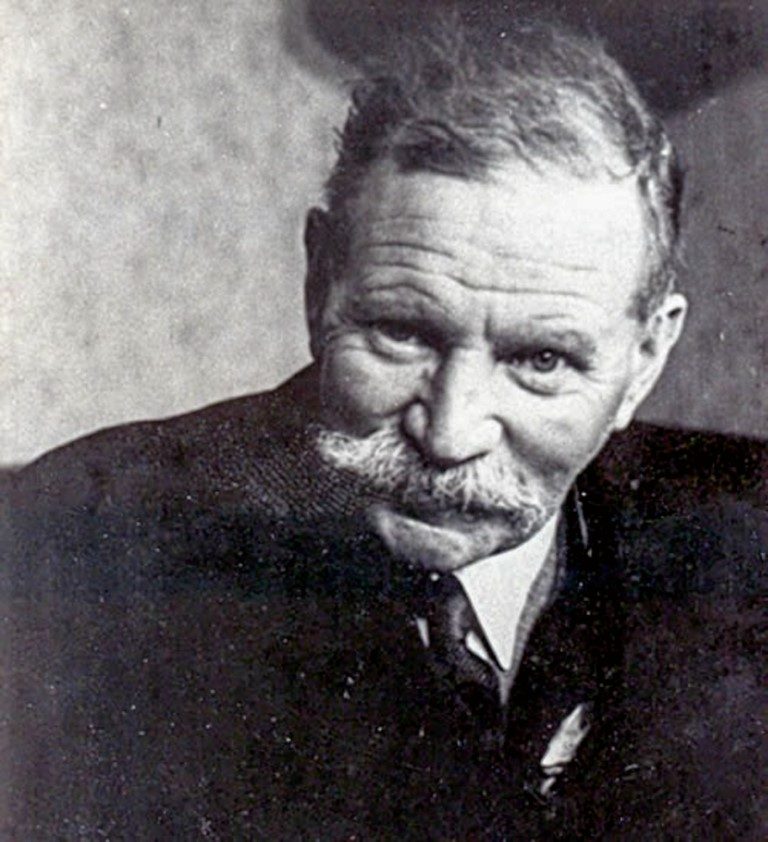

There were many parallels between the situation in 1918 and today. Our public health officials had excellent training in epidemics and established protocols which, despite being a century old, have saved countless lives in this Covid-19 outbreak. Among those officials were two well-known yachtsmen, Dr Robert Haldane Makgill, the Acting Chief Medical Officer, and Dr Herbert Chesson, Christchurch’s Medical Officer, who became two of the local heroes of the Spanish Flu.

Health Officers throughout the country issued warnings and directions which had almost exactly the same themes as in 2020, closing schools, pubs, businesses and picture theatres and cancelling public meetings and sporting events, detailing the need for self-distancing and isolation and a making a strong emphasis on personal hygiene.

The sneezing, coughing and breathing vectors were well known. They placed emphasis on getting out into the open air. Despite that, the virus got a fresh start when the whole country went out on the streets to celebrate the Armistice on November 11. Only Coromandel closed roads in and out, with success. In mid-December 1918 cases began to dwindle and the last cases came in January 1919.

Lawrence, Editor of Boating NZ, has asked me to comment on how the Spanish Flu affected the sport of yachting and the boatbuilding trade in New Zealand. Pleasure boating had dwindled during the course of the war. Yachtsmen were among the first to volunteer and most of the larger yachts were promptly laid up “for the duration”.

Yacht clubs did their best to keep harbour races going but it began to feel unpatriotic to race. Fuel for launches was restricted, but the major restriction was the prohibition against going outside harbour limits without special authority, strictly supervised by guard vessels and the coastal artillery batteries.

Throughout the war, however, yacht and motor boat clubs arranged harbour events where returned servicemen were taken out for recreation. Because a very large proportion of yachtsmen had volunteered early, young lads often filled out the crews and gained great experience for their post-war racing. Because of the epidemic the yacht clubs around the country postponed their normal November Opening Days.

But by mid-December cases were tapering off. Races and cruising outside the harbour were resumed. The Auckland and Wellington Anniversary Regattas in January 1919 went ahead and were well attended.

After over four years of brutal warfare, it was a great joy to be back on the water. War heroes, like Cyril Bassett VC in his keel yacht Peri, were seen out on the water to defy the horrors of the war and the gloom of the new epidemic. Of course, servicemen were still trickling back into the country until well into 1919, especially those who had been posted to the Allied Occupation of cities like Cologne in Germany.

Not surprisingly, after the double dreadfulness everyone had just experienced, 1919 brought with it an unprecedented boom in yachting throughout the country. It was largely among youngsters in the centreboard classes, like the 14ft One Design Class (later X Class) favoured by our new Governor-General, the hero of the battle of Jutland, Lord Jellicoe, and the 14ft square bilge Y Class promoted by George Honour in Auckland but with firm roots in Wellington. It also brought a huge boom in launch building (see Vintage View, February 2019).

Our boat-building industry had already scaled down during the War, especially after Gallipoli. Right from August 1914, a large proportion of tradesmen had volunteered for active service. Most young men had trained as Territorials for some years past. For example, Joe Jukes of Wellington volunteered immediately, and left with the Main Body on October 16, 1914 as a Sapper in the Engineers.

The main concern was to maintain a competent work force for shipwright and repair work on the large number of essential vessels trading through our harbours in wartime. Supplies of boatbuilding materials and marine hardware became scarce.

The demand for new yachts had vanished. While a limited number of launches continued to be built, they were mainly for essential commercial work, but the supply of engines from overseas, then mainly from America, slowly dried up, especially when the US went on to a war footing in April 1917.

Local companies like Zealandia, Kapai, Anderson and Orion had been providing practical, low-to-medium horsepower marine engines for some time, but there was no local volume manufacturer of heavy duty engines until W.R. Twigg of Auckland got into modest production of the Twigg engine in a range of outputs by 1919.

So, by the time of the flu epidemic in late 1918, our ship and boatbuilders had not even begun to return to pre-war volumes. Many boatbuilders were still overseas. For example, Ted Le Huquet, an RNVR Lieutenant in the Motor Launch Flotilla on the Rhine, did not get back to Auckland until May 1919 to resume his father’s business in Devonport.

After the Spanish Flu had waned, apart from sporadic new outbreaks, the Government conducted a Royal Commission Inquiry in 1919. Dr Makgill was a major contributor, preparing the report on behalf of the Health Department. He emphasised the need for immediate scientific control of epidemics and the avoidance of political interference and management, a theme topical in the US as I write.

The Inquiry resulted in the passing of the Health Act of 1920 which Dr Makgill largely drafted. That Act, reckoned worldwide to be a model of its kind, gave teeth to the Health Officers’ demand for an apolitical and totally scientific approach to public health and epidemics.

Contrasting New Zealand’s mortality rates in both epidemics, a century apart, should make us proud of two pioneering yachtsmen, Drs Makgill and Chesson. The story of their yachting exploits must wait until next month.

TELL YOUR STORY

Do you have a vintage story you would like to share with our readers?

Contact Harold at: haroldkidd@boatingnz.co.nz