Alex and Lesley Stone venture up the ultimate creek…

Our Up the Creek adventure this month breaks all the rules. For a start, we’re not starting at the river mouth. And our ‘creek’ is the mighty Waikato, New Zealand’s longest river.

To do this justice as an Up the Creek adventure would take an entire book – or two. So we’ll just do the bit through the city of Hamilton. A journey that can as easily be accomplished by bicycle along the riverside Te Awa Trail, if you have shipmates with this preference.

We will launch at the Puketu boat ramp car park, just by the Waikato Equestrian Centre, and head up to Hamilton Gardens and back. There’s enough history – and contemporary cultural interest – in this short stretch anyway.

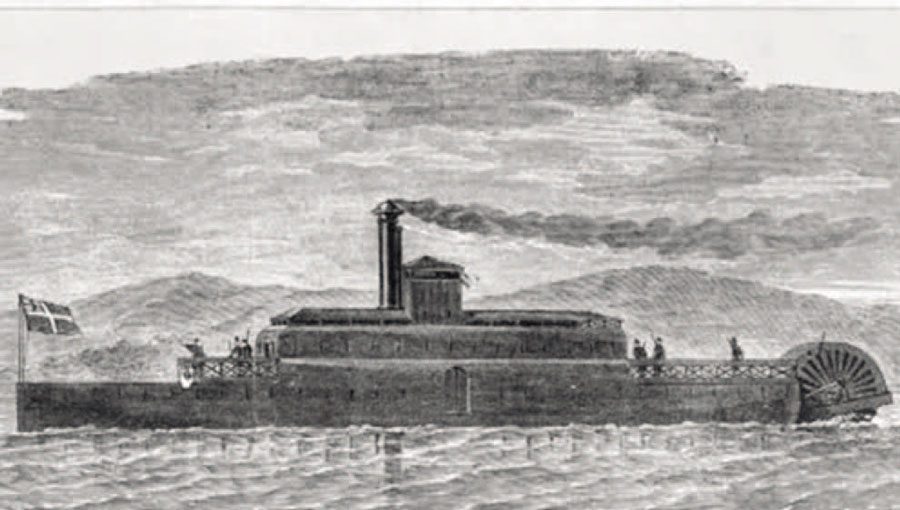

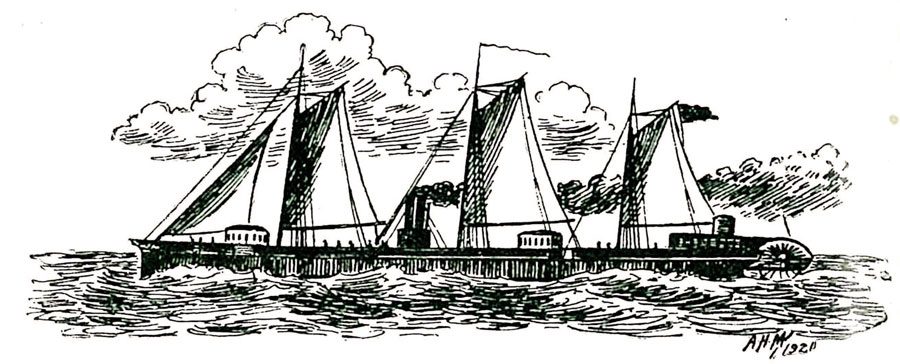

Captain Steele’s gunboat Rangiriri.

Captain Steele’s gunboat Rangiriri.

It’s said of the mighty Waikato River that there’s a Rangatira, a chief, living at every bend. And in between a taniwha or two, as well. Mythic and other histories overlap closely here.

This great sense of history’s presence is a strong feeling as you take your boat up the river. You’re following the ghosts of many boats before you.

So our wee inland boating voyage is upstream past central Hamilton with its many museums, competing sculptures, boathouses, murals, and the best collection of second-hand bookshops in the country, to the lovely Hamilton Gardens and the friendly folk in the café there. They saved my life, sort-of, as I had reached terminal munchies by the time we got there. It was Lesley’s frequent photo stops that had held us up – but it was all fun anyway.

For cyclists it’s a fine ride, and easy too, as the path mostly follows the river. There are a few short, steeper bits where the path angles up a river-side bluff, but generally it’s all easy going – especially downstream, with the implacable, deepgreen river your constant companion just past your right handlebar.

This section of the river passes under half-a-dozen bridges, which is still a limited number for a city of Hamilton’s size. I imagine it still leads to a difference between East and West Hamilton. Which is a long-standing thing.

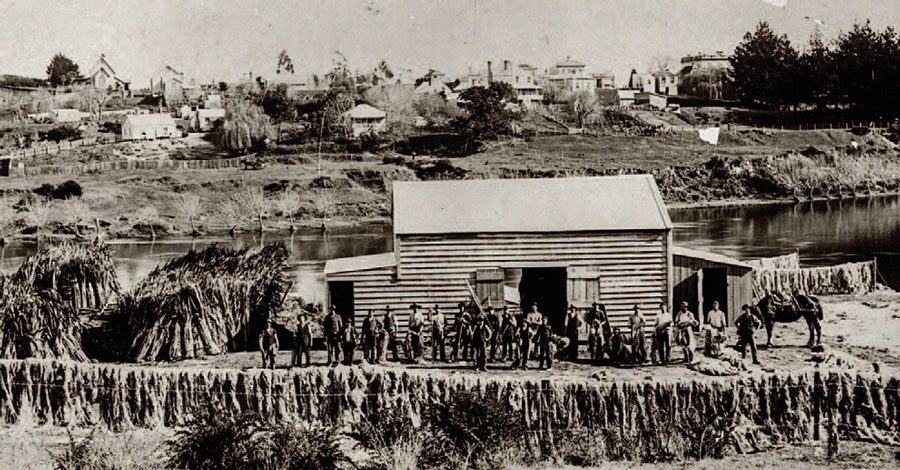

Isaac Coates’ flax mill, 1898 (Hamilton City Libraries)

Isaac Coates’ flax mill, 1898 (Hamilton City Libraries)

For when the 4th Regiment of Waikato Militia established the settlement at a small kaianga called Kirikiriroa (meaning, a long stretch of gravel) in 1864, it certainly didn’t seem a likely location. Kirikiriroa had been abandoned by Ngati Wairere temporarily during the Musket Wars in the 1820s. But between 1845 and 1855 wheat, fruit and potatoes were exported to Auckland from here, with up to 50 waka plying that trade from Kirikiriroa. In August of 1864, Captain William Steele stepped ashore from the gunboat Rangiriri and established the first British military redoubt near what is now Memorial Park. He was among the vanguard of the invasion of the Waikato, a military campaign using the river as its vector. The repercussions of the raupatu (land confiscations) that followed the Invasion reverberate even now.

For those interested in the river as the main front of the war, the 2014 book The Waikato River Gunboats, self-published by Grant Middlemiss, is a worthwhile read. It’s available from his website http://www.waikatorivergunboats.com

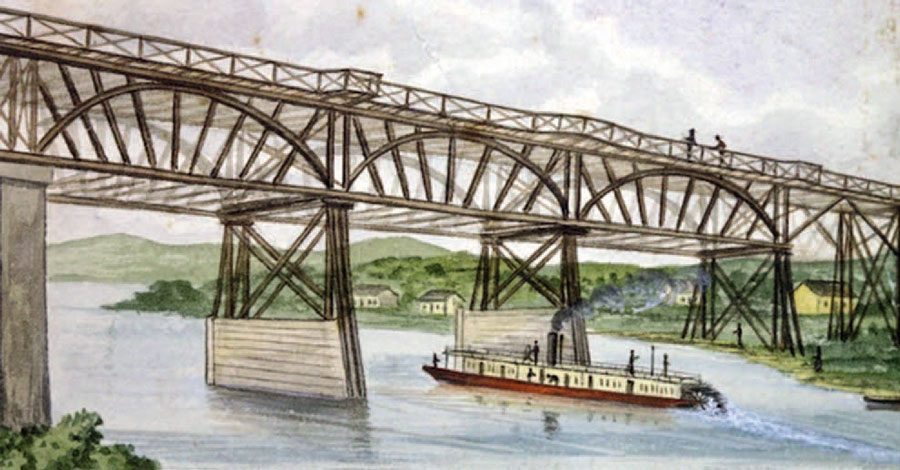

Te Awa River Ride.

Te Awa River Ride.

The settlement’s new name, incidentally, came from a Captain John Charles Fane Hamilton, commander of HMS Esk, one of the naval squadron in New Zealand during the conflict in the Waikato. He lost his life in the Battle at Gate Pā, Tauranga, in 1864.

Surrounded on all sides by marshlands, the settlement – on both banks of the river – initially grew very slowly. The people of both Hamiltons (East and West) were connected, tenuously, by means of a punt service across the Waikato River.

By combining, they managed to get a government loan for a bridge in December 1877. Union Bridge was completed the next year.

Te Awa River Ride near Pukete

Te Awa River Ride near Pukete

By 1911 Hamilton’s population was still only 3,542 – about half the size of Waihī, then a gold town at the height of its boom times.

Hamilton began growing quickly after the First World War, with the land surrounding it being drained to make paddocks, and the growth of the Waikato dairy industry.

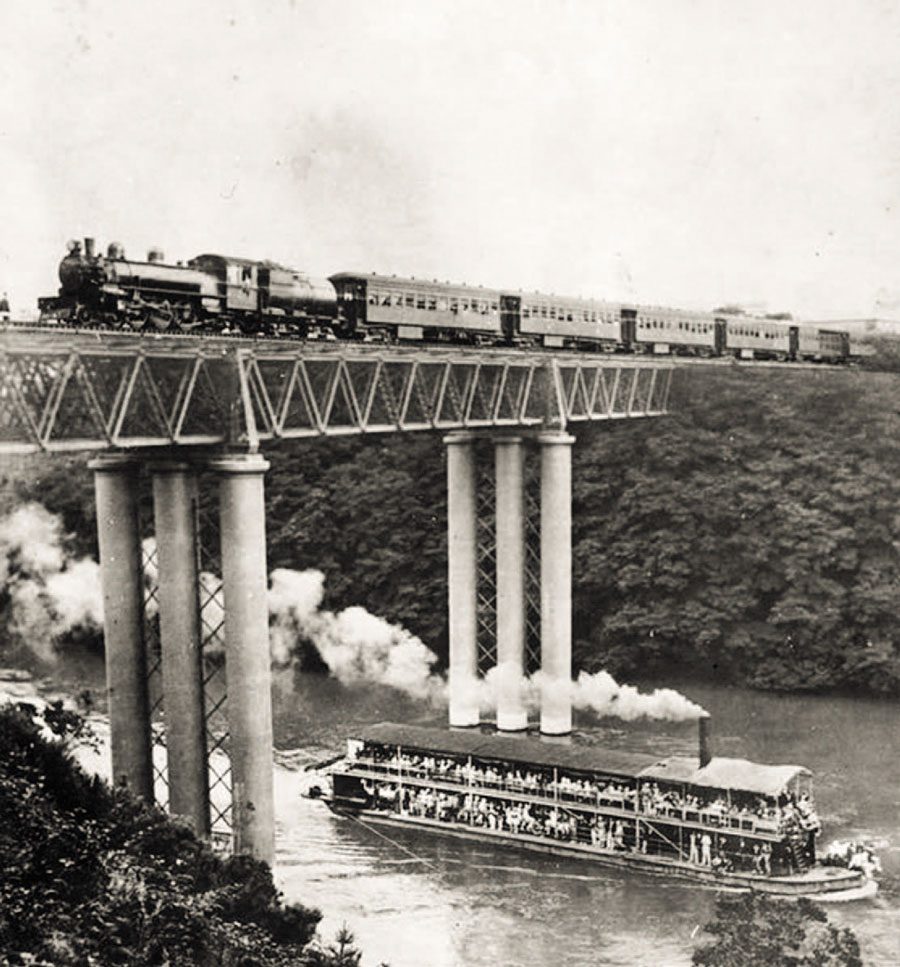

Hamilton became a thriving inland port, serviced by a number of steamers. The riverboats included the former gunboat Rangiriri (now lying as a riverbank relic opposite Hamilton Central), and others such as Bluenose, Waipā, Delta, Freetrader, Rawhiti II and Waikato.

Tight parking on the bows of Rawhiti on her maiden voyage in 1925. (Hamilton City Libraries.)

Tight parking on the bows of Rawhiti on her maiden voyage in 1925. (Hamilton City Libraries.)

The travel costs: “In 1876, Waikato Steam Navigation advertised freight from Auckland to Cambridge and Alexandra as: Up river 45/- [45 shillings, or 2 5s] a ton; Down rivers 35/- a ton; Timber 3/- a 100 ft; Cabin passenger 5/-; Deck passenger 3/6 [3 shillings 6 pence]; Horse 5/-; Buggy 5/-.

But the river boats faded away. In 1927 they had a bad year, constantly running aground due to low river levels caused by the filling of dams upriver. The last time-tabled services – those of legendary skipper and ship-owner Ceaser Roose’s line – ended in 1946.

Now the Waikato River is a mecca, instead, for recreational craft. At Hamilton centre, there are rowing and waka ama clubs, obviously well-supported, with dozens of boats at their disposal. And next door, somewhat surprisingly, the impressive headquarters of the Waikato Sport Fishing Club, which has most of its activities as sea fishing, including family events at Raglan and Shelley Beach in the Coromandel.

PS Manuwai, a paddle steamer, on the river in the 1920s.

PS Manuwai, a paddle steamer, on the river in the 1920s.

We tie up at a new jetty enlivened by some glittering pou sculptures. The artworks were a collaboration between hapū representatives and artist Eugene Kara of Ngāti Korokī Kahukura.

Kara says the design was inspired by the stories told within each hapū about their genealogy and history with the river. Just opposite is a place to land and visit the hull of the Rangiriri.

Head down, puffing up the steep incline of the loop of the trail that leads up to Hamilton city centre, I – oops! – inadvertently go between a camera crew and the good blokes of the New Zealand test cricket team. World champions! And doing a tour from Bluff to Whangarei to show off their trophy, a gilded mace. They looked like healthy young fellows, so I avoided what must be a weary joke for them, about a sporting trophy that cannot hold champagne.

High fashion on the steamer Rawhiti’s maiden voyage, 1925. (Hamilton City Libraries)

High fashion on the steamer Rawhiti’s maiden voyage, 1925. (Hamilton City Libraries)

Once atop the riverside bluff, the ‘Victoria on the River’ plaza that opens Hamilton city centre to the river, offers a splendid view across to Hamilton East. That view is artfully framed by a major archway work in Corten steel by the Māori sculptor Robert Jahnke. There are terrific, huge murals of a kārearea New Zealand falcon, and a kōkako. But somehow the city still seems divided. The CBD is all on this side of the river.

The two-part nature of Hamilton even now is symbolically reflected in the two bronze statues that define its main centre. And the two significant works by Māori sculptors too, Jahnke’s and Michael Parekowhai’s multi-coloured The Tongue of the Dog, outside the Waikato Museum.

A Waikato River gunboat.

A Waikato River gunboat.

The two bronzes are of Sapper Horace Moore-Jones, the celebrated First World War artist who recorded all the tragedy of Gallipoli. Including with his famous watercolour of Man With the Donkey, acclaimed one of the most important pieces of Australasian war art, symbolic of the nation-building sacrifice of war and birth of our nationhood. Rarely recognised these days, the artist died in 1922 rescuing women trapped in a hotel fire.

The Moore-Jones statue was created by New Zealand Defence Force artist Captain Matt Gauldie – the Gallipoli stone plinth it crouches on was gifted by the Turkish Government.

Te Awa River Ride mural ‘A Love Story’ by Charles & Janine Williams.

Te Awa River Ride mural ‘A Love Story’ by Charles & Janine Williams.

An equal story, internationally, is that of another Hamilton-born son Richard O’Brien (creator of The Rocky Horror Picture Show) who initially played its androgenous central character Riff Raff. The statue of Riff Raff is very close to that of Sapper Moore-Jones – but they are worlds apart. Cast in different styles and attitudes. Moore-Jones is ruggedly moulded, and crouches with arm outstretched, measuring with a pencil as artists do – but clad in full battle gear.

Riff Raff is dressed up too – but in his own unique style. The smooth finish of this bronze is appropriately slick, with detailing – like the stretching of his suspender tights on his thighs – finely rendered by sculptors at Weta Workshops. His weapon is a shiny stainless steel ray-gun thing.

Te Awa River Ride, Hamilton Gardens bridge.

Te Awa River Ride, Hamilton Gardens bridge.

This artwork marked the site of the barbershop (long gone) where O’Brien worked in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Riff Raff is revealed in full alien regalia from when he time-warps from the fictional planet Transsexual. Near the statue were posted instructions on how to do the ‘Time Warp’ (again).

That Sapper Moore-Jones and Riff Raff are so close, yet out of line-of-sight of each other, and given their orientation would be averting their gazes anyway, adds further symbolism to the city centre’s sculpture-scape. For the moment, Riff Raff is completely hidden from view, as renovation proceeds on the regional theatre there. The good folk at Hamilton say he will be returned – promise!

Te Awa River Ride mural by Poihakena Ngawati.

Te Awa River Ride mural by Poihakena Ngawati.

One more thing about Hamilton’s central city sculptures. On 12 June 2020, the City Council removed the statue of Captain Hamilton himself, at the request of the Waikato Tainui iwi. This particular statue had passed its comfortable use-by date, with its association with the New Zealand Wars, racism and colonialism. At the same time a local kaumatua, Taitimu Maipi, who had vandalised the statue in 2018, called for the city to be renamed Kirikiriroa, its original name in te reo Māori.

What about stopping on the riverbank and casting a line to try your luck at fishing? But does the fact that the Sport Fishing Club is more focused on sea-water recreational angling mean anything?

Riverbank houses.

Riverbank houses.

Not really, says Bob Gutsell of the Freshwater Angling Club, which shares the clubhouse. Bob tells me that large brown trout are often seen in the river right there; and that casting a spinner for them is your likely best bet. Remember, all fishing for trout in New Zealand requires permits. You can also try fishing for koi carp and mullet, both vegetarian fish – so you’ll need appropriate bait. The mullet, sometimes seen in schools even this far upriver, are a fish that come from the sea. And, of course, the river is the haunt of eels, some really, really big. A third, and funky mural in Victoria Plaza, curiously features a giant eel, fishing (for itself? one wonders) in the river.

The boat ramp by the fishing clubs is busy at times, shared by waka ama, kayaks, rowing shells, rowing coaches’ boats, and many recreational motorboats.

Te Awa River Ride bronze ‘Riff Raff’ by Weta Workshops

Te Awa River Ride bronze ‘Riff Raff’ by Weta Workshops

There’s good directional signage on the Te Awa trail, but very little in the way of informative panels – except for those outlining public artworks. Which is a pity. For I reckon there’d be stories aplenty to tell along the river banks. The bridges for example – they each must have had compelling reasons to be built. One bridge is a double-decker, carrying the main railway line under the road deck. And the signs are all arranged for people on the land.

I would have liked to learn more about the ecology and dynamics of the river. There were plenty of signs telling us it is very dangerous to swim in, but without giving the reasons why. Mind you, the deep green, swirling water did appear ominous enough by itself.

Hamilton Gardens lake sculpture.

Hamilton Gardens lake sculpture.

All of that natural and cultural history is covered, fulsomely and well, in the book The Waikato: A History of New Zealand’s Greatest River (2018, Bateman Books) by celebrated historian Paul Moon.

Also, the history of Hamilton city itself – and its relationship with its partner, the river – has many twists and turns. But on our day there, we found the river unusually quiet. No rangatira. No taniwha. Just the memories of thousands of boats before us.

The steamer Bluenose at Hamilton Wharf, 1873.

The steamer Bluenose at Hamilton Wharf, 1873.

Like so many domestic tourism attractions in New Zealand right now, it’s there for us to enjoy without the many international tourists. And it’s part of the ultimate Up the Creek. BNZ