It was that time, writes Matt Vance. We needed a new engine. All boat owners know the time when it comes. You can ignore it for a while, but eventually it has the loud insistence of someone knocking on your door on a dark, rainy night.

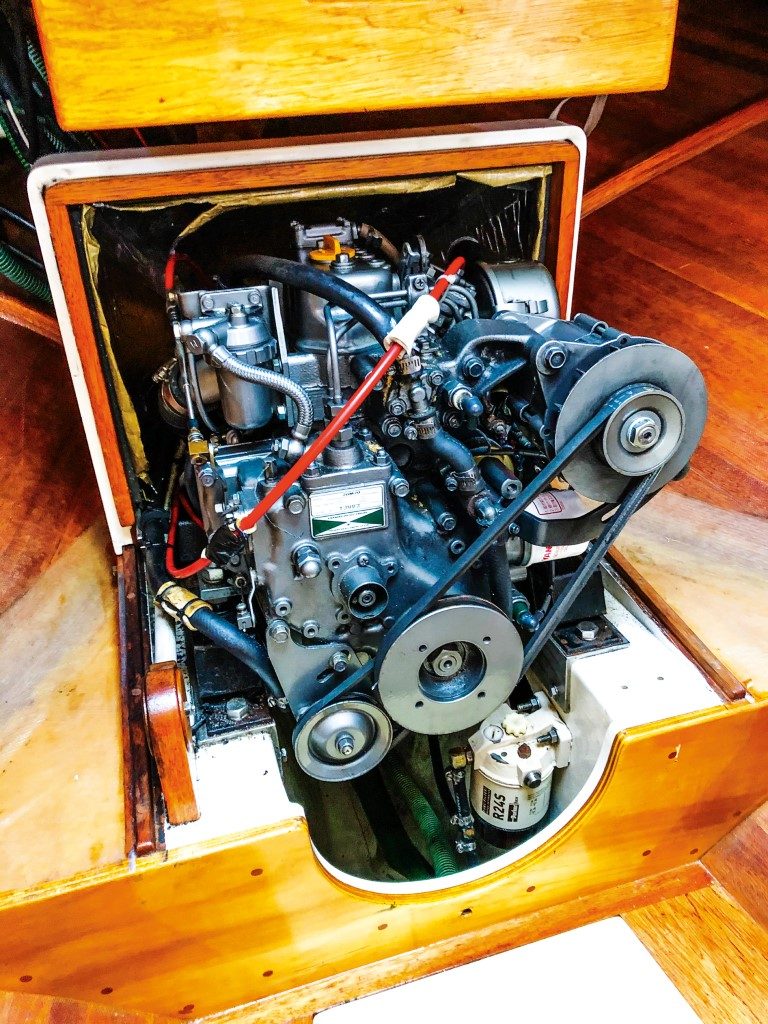

Our 26-year-old saltwater-cooled Yanmar 2GM20 had done faithful service, but it was that time. A Yanmar 3YM20 was ordered from our local Yanmar dealer, Mainland Marine. It came in a sturdy plywood box and with a comprehensive set of instructions, yet nowhere in the manual did it mention that I was going to need a psychiatrist.

Whitney Rose was duly hauled out on a cool winter’s day and allocated a slot in the yard next to my friend Dan’s boat. He quickly assessed my predicament and declared, “You’re going to need a psychiatrist.” Luckily for me, he is one.

I have the odd habit of referring to my friends by their profession and quickly introduced Dan to my neighbours and yard loafers as “my psychiatrist.” At this beaming revelation from me, there would be a brief clearing of the throat while they developed an intense interest in their shoes. This was usually followed by an awkward silence before they remembered they had to go mix epoxy or something.

Being an ignorant patient has never been my thing, so I legged it to the local library and got out a copy of The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). My psychiatrist said, “I’m not sure that’s a good idea. Most people will find something of themselves in there and you can just tie yourself up in knots by reading it.” I wholeheartedly ignored his advice, tucked it under my arm and boxed on with the engine repower project.

The first hurdle came the next day when we had to remove the solid dodger off Whitney Rose to allow us to get the engine out the hatchway. “We’ll just whip that off,” I said, before spending the next few hours trying to remember where the side bolts were connected. It was the first of many small challenges to come.

I had visions of us not being able to get the dodger off without a chainsaw. My psychiatrist turned up as I sat slumped morosely in the cockpit. With a positive attitude and a chisel, he carved into where we thought the bolts were bogged in. It felt personal. He chipped away and before long we had undone the mysterious bolts, popped the dodger off and deposited it on the foredeck. Turns out Dan was right about needing a psychiatrist.

There are those who are mechanically-minded and there are those who are not. Being a capricious, artistic type I fall into the ‘those who are not’ category. With this ineptitude firmly in mind, I engaged Brian Bone of Mainland Marine to oversee the whole repower project. Brian is a man of few words but when he does speak it pays to listen. He turned up with a handful of tools and said, “We’ll just whip that old motor out, eh?”

Unlike me, he meant it. Within 50 minutes he had disconnected the whole power plant and with the assistance of my attorney (he admits to being mostly drunk at law school) we were guiding the old Yanmar out of the hatchway and onto Brian’s truck.

Watching Brian work away I noticed he had a knack for not getting too excited nor too downhearted. He had a level and consistent personality and persistence that lent itself to solving complex mechanical problems. When I can’t get a bolt out,

I take it personally and fall into the depths of despair. Not Brian, he only hums away, and if he offers up anything at all,

it will be a positive “It’ll come.”

Because of this personality fault of mine, I am a little prone to profanity in these situations. “I’ve got sporadic onset Tourette’s Syndrome,” I declared. “There is no such thing as sporadic Tourette’s, Matt. Look it up in the DSM,” said my psychiatrist.

After Brian had departed for the day, I decided to refer to him as “my mechanic.” Down below there was now only the yawning crevasse of Whitney Rose’s bilge and a faint waft of diesel to remind me of the old motor’s presence. The crevasse had collected an impressive range of dropped tools and fasteners over the years and once these had been liberated from their internment I set about cleaning and painting the bilge.

Before he left, my mechanic had said, “You can whip those stainless L-brackets out for me and bring them up to the workshop.” He must have noticed my face turning pale as he added, “You can do it.” It took me four hours as it was well bolted to the engine-beds and it required some contortion and several attacks of my apparently non-existent sporadic Tourette’s syndrome to get them off.

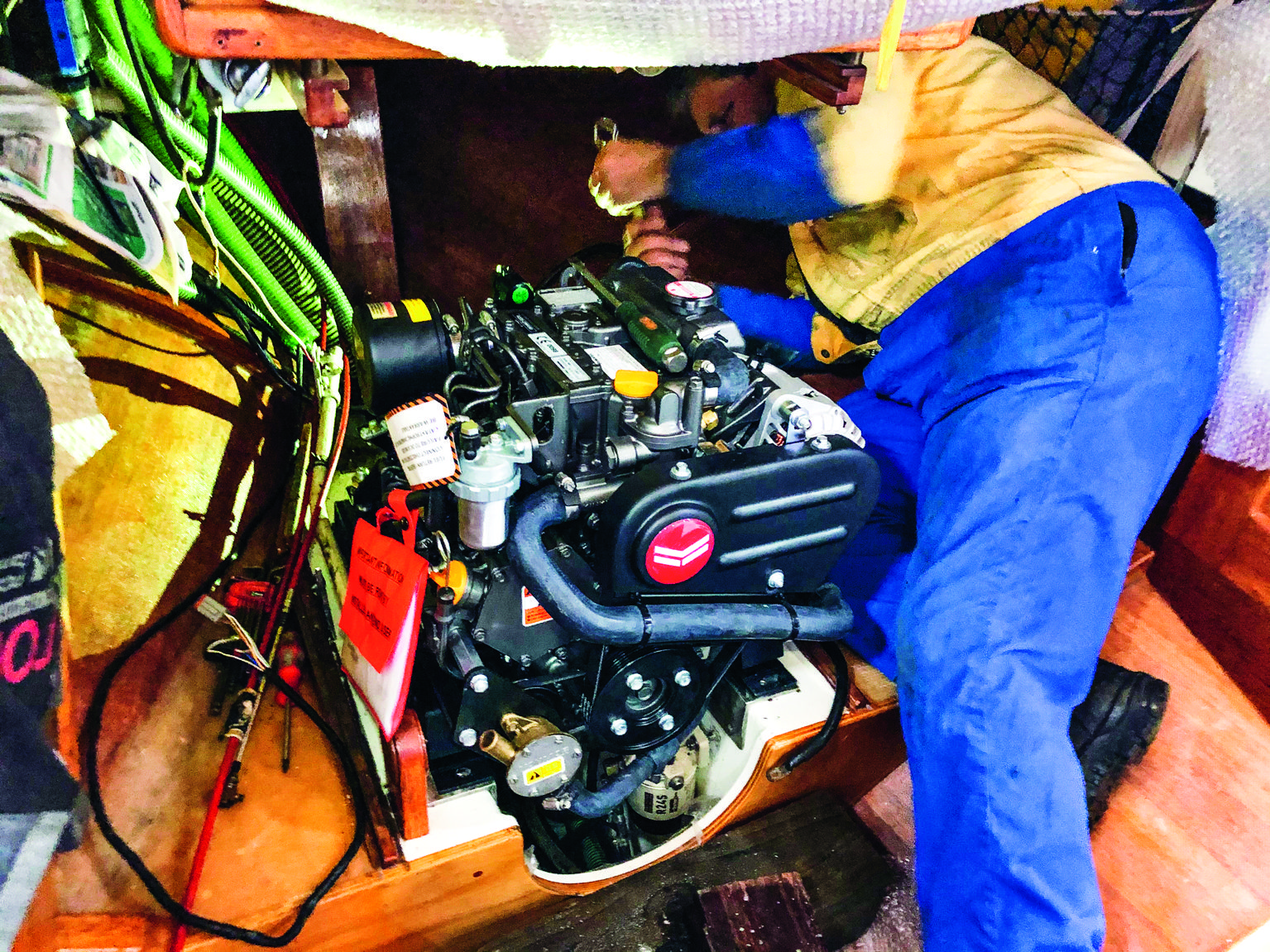

Thanks to having an extra cylinder, the new engine was 52mm longer between mounts, so my mechanic set about cutting them and welding a new midsection at his workshop. While this was going on I was allowed a peek inside the box at the new 3YM20. It was like looking at a newborn baby in its bassinette; it made me feel all warm inside.

Back on board the crevasse was as shiny as a hospital ward – and I boasted about it on Facebook. Not long after, as my mechanic and I were removing the water lock muffler, I managed to dump a load of sooty, greasy exhaust water into the bilge. It was never to look like a hospital ward again.

With everything back in, it was time for the new engine to be swung in. My attorney and psychiatrist were nowhere to be seen, so my mechanic and I did it using our cell phones on speaker while he worked the hiab from the truck and I guided its gleaming paintwork through the hatchway. With the aid of some four-by-twos, we levered and wiggled it into position.

Over the next while he set about connecting the vitals to the engine. There were a couple of times when it looked like we might have to move the engine to get at another part of the exhaust and I fell into a deep depression. For a change I consulted my attorney who said, “Have you tried rum?”

While we were in this process my psychiatrist made a house call to the boat. When he glanced down the hatch, he looked visibly shocked. “I have never seen this boat in such a mess,” he said. “I think you are suffering from Diogenes syndrome.”

I had to look that up in the DSM when he was gone. It was named after the ancient Greek philosopher who it is said lived in a barrel and is a condition that affects elderly patients who fall into a self-imposed prison of neglect for themselves and their surroundings.

I tidied up a bit after that and before long we were ready to relaunch Whitney Rose for commissioning the engine.

In the good old days, you could just chuck a new engine in and bugger off. These days engine manufacturers must be certain the engine is installed correctly and meets certain criteria that give it a fighting chance of being reliable. My mechanic came aboard with all the tools for measuring backpressure, rpm and temperature.

Fitted with our existing prop, we could only get to 200rpm below maximum revs, which meant we were over-propped and more importantly, unwarrantable.

We went back on the cradle without so much as a swear word. My mechanic knew what to do. He whipped the prop off and sent it to Bri-Ski in Maramarua where it had a quarter of an inch skillfully knocked out of its pitch. I retreated to the pub with my attorney where we talked rpm, pitch and rum.

The next attempt was a far more relaxed affair. We all knew what to expect. My mechanic grinned as he showed me his hand-held rev counter with the magic 3600 flashing on its digital display. We went up and down the harbour while he recorded the various rev settings. From a distance, it looked like we were mowing the lawns. Onboard, my attorney talked excitedly while I just felt relieved. The new engine purred like a kitten.