Recalling an inland delivery trip long ago in a land far away.

The muddy brown creek marked the Florida–Georgia state line.

The green, stygian forest of a national park crowded the north bank and on the Florida side, Hermanson’s Boatyard scrabbled a living on a clear strip surrounded by swamp grass and mangroves.

We had been there for a few months, doing a major refit on our steel cutter Elkouba – and I mean major refit. A large portion of her decks had been removed and a deckhouse fitted, I had sandblasted and spray-painted her hull and virtually rebuilt the interior.

We’d got to know the locals and had become almost local ourselves. Among the boatyard workers there was Charlie, a nuggety good ol’ boy who habitually wore camouflage gear. He worked a trapline catching raccoons in the national park across the creek. Most of the carcasses were sold to Afro-Americans in Fernandina Beach township who called him “the coon man.”….until the morning he was escorted to work by heavily-armed Georgia park rangers and taken away by the local police.

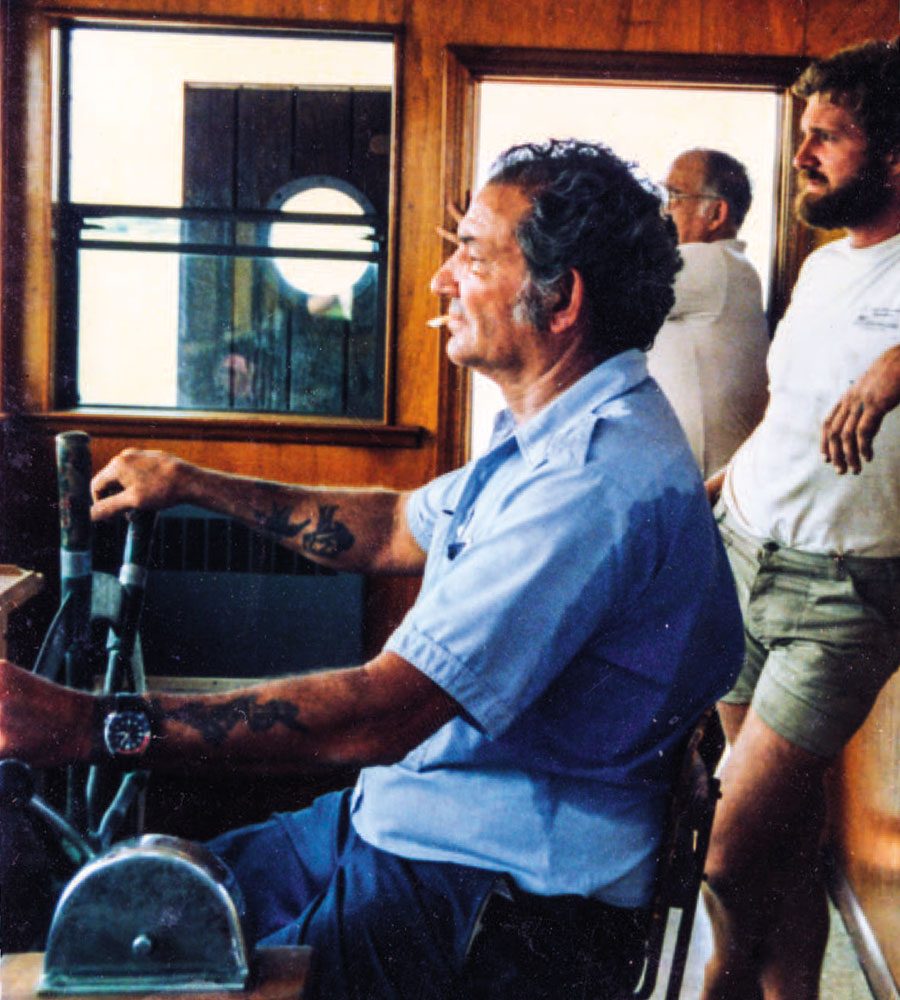

Dougie at the wheel of the General, the writer keeping watch on his shoulder.

Dougie at the wheel of the General, the writer keeping watch on his shoulder.

“I was jes emptying my traps,” he told me later ,” when I heared the walkie-talkies….and I knowed I was busted.”

Our local bar was a small shack, called Shrimp Haven, near the jetty, at the end of a rickety boardwalk through the swamp. Local shrimpers gathered in the evening to drink Budweiser (“we call it Butt-wiper”) and tell fishing stories.

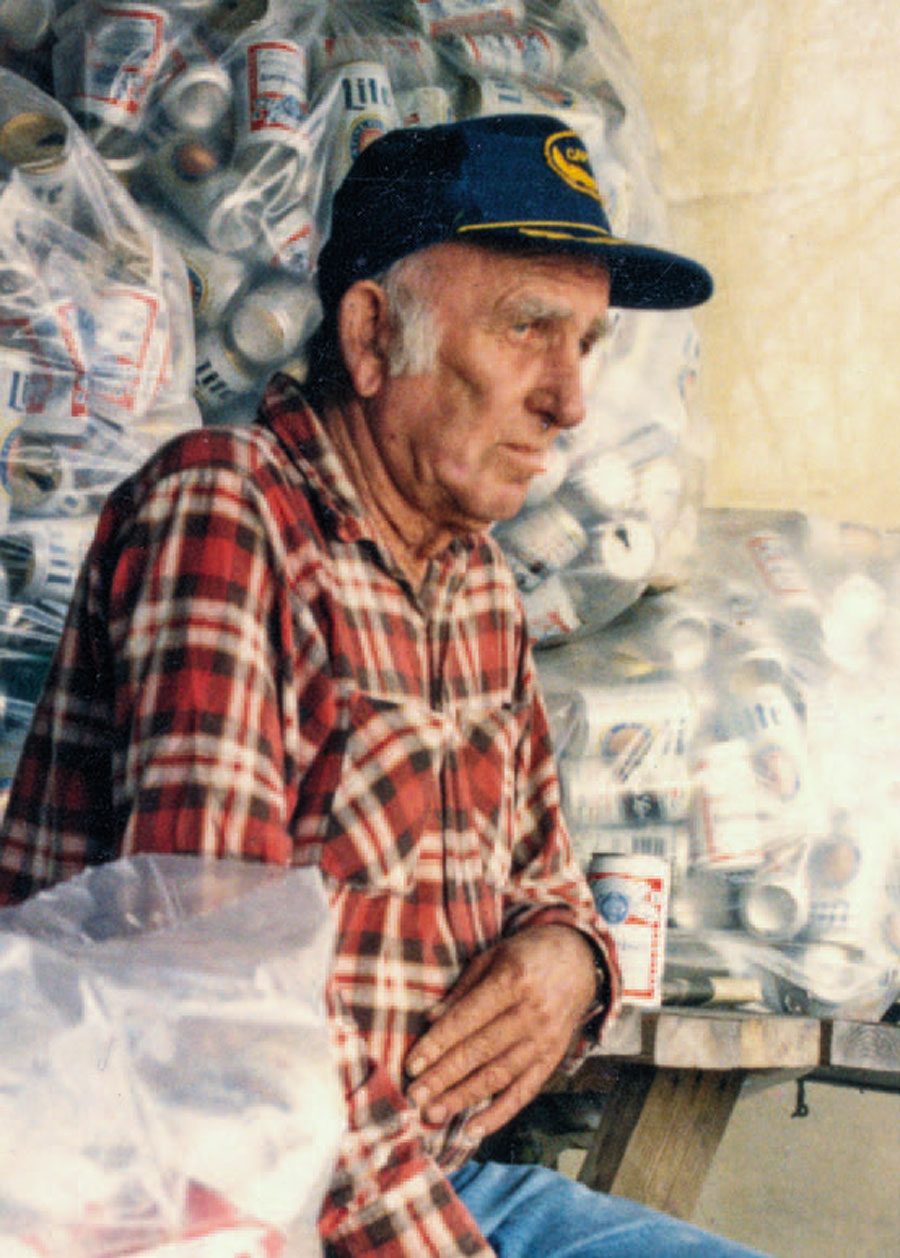

Big plastic bags full of empty beer cans crowded the back doorway.

I’d been a commercial fisherman in New Zealand and enjoyed swapping yarns… they asked how our refit was going, where New Zealand was – they figured it had to be near New York someplace because of my funny accent and because both places shared the same first name.

Or maybe Canada someplace?

Further down the creek a small black bulk ship was tied to a wharf by chafed and furry dock lines. Stickers slathered all over the ship proclaimed that she was the property of the US Government and trespassers would be gunned down, blown up, eviscerated and stabbed. ‘General’ was crudely brushed on the bows in white paint which had dribbled lavishly during its application. Smears of rust ran down the hull.

The General tied up to a rickety jetty in the creek.

The General tied up to a rickety jetty in the creek.

Like good boat folk, we ignored the signs, peered through the wheelhouse windows and lifted a corner of the hatch covers to look into the hold. A few hundred tonnes of sand were mounded in the centre of the hold.

“Ain’t nothing but a Cuban dirt box,” one of my companions said.

It turned out the ship had been running refugees from Cuba when she’d been stopped by the US Coastguard. The refugees had been imprisoned or deported and the ship had been confiscated and tied alongside the derelict wharf.

“I got a job for it,” Dougie said. “I’m gonna buy it.”

He already ran a high-lining shrimp boat – about 12m long. What could he want a 50 or 60m ship for?

We strolled back through the swamp to the Shrimp Haven with its single beer bill of fare.

Big plastic bags of empty beer cans crowded the back door of the Shrimp Shack.

Big plastic bags of empty beer cans crowded the back door of the Shrimp Shack.

Then, a couple of months later, Dougie strutted into the Shrimp Haven. “Well,” he said, “I done it – I done bought the General.”

Over a few Butt-wipers he outlined his plans. He was going to take the ship to Jacksonville, about 30 miles south, to rebuild her as mothership for a fleet of scallop fishing dories. “Ain’t nobody never done it,” he grinned, “we’s gonna make us a fortune!”

And a week later he swung by the boatyard. “Hey Lenzee,” he asked, “reckon you could run the General down to Jacksonville for me?”

“Yeah, no problem,” I said and, when he’d left, I wondered what the hell I’d done.”

The first thing was to take a tape measure down to the General. Most of the road bridges over the Intracoastal Waterway between us and Jacksonville were manned and would open on demand with a VHF call. The others had a statutory clearance of 40’ (12m). With the tape measure I figured our air draught (height). We could make it with about 60cm to spare.

The Fourth of July in Edgarstown, Florida, 1986.

The Fourth of July in Edgarstown, Florida, 1986.

Width was another matter, but I figured we could sneak through the narrowest spots with our 10m beam and, as for depth, some of the ‘Cuban dirt box’ would have to go.

The next plan was to slap a mask and snorkel on and check out the propeller and rudder, but my workmates warned against it. “Them ol’ alligators will eat your goddamn legs off!” they advised. So I firmly crossed my fingers, hoped all was well, and stayed on dry land.

We trooped below to check out the engine room. Main

power was a 12V92 Detroit Diesel. This huge green pile of machinery was one of a series of two-stroke engines designed for the US military. The appellation means 12 cylinders, in a vee configuration and 92 cubic inches per cylinder displacement. It produces about 700hp (522kW) at 2,100 rpm.

I checked the fuel filters and engine/gearbox oil, opened the sea cocks and hit the start button. It tried to go but couldn’t quite overcome the compression in all 12 cylinders.

But I had been shipmates with 471 and 671 Detroits in New Zealand and had learned how to get a reluctant one running. One of the guys brought a newspaper down from the messroom which I rolled into a tight cylinder (or torch). The shrimpers peered over my shoulders to see what I was doing and I borrowed a cigarette lighter.

I opened the throttle slightly, set fire to the end of the rolled up newspaper, and pushed the start button. I thrust the burning paper into the air intake, the flame was sucked into the intake (the newspaper and my hand almost went with it). The engine cranked one….twice…then let out a loud bang and roared into life at about 1,800 rpm.

Elkouba’s refit at Hermanson’s Boatyard beside a muddy creek on the Georgia-Florida state line coming along nicely.

An engine the size of a Toyota Corolla, starting from dead cold to full flight in seconds – I’m sure that was the beginning of the hearing loss I suffered in later years. I looked around triumphantly to see if my buddies were as impressed as I was – but there was no-one to be seen except for one pair of outbound work boots fleeing through a bulkhead door.

The engine tappets rattled like castanets at a Spanish festival and the engine screamed the typical high-pitched Detroit bellow. The face of the cooling water pump was cool – indicating that water was getting through and on deck a small geyser of cooling water hosed overboard. The rev counter didn’t work, but after I’d tapped it a few times, it shrugged and swung into life.

I gave the engine a few revs….all good there. But I didn’t dare try it in gear in case I tore the wharf away from its swampy anchorage.

The creek was about 40m wide and the General was about 50m long….I could foresee problems turning her round and heading downstream but the skipper of a local pusher tug agreed to hang off our bow and steer the ship while she backed downstream.

I had a few sleepless nights before, on the appointed day at high water, we fired up the big Detroit, took lines from the tug boat and loaded a pickup truck-load of Butt-wiper on board.

Extricating the General from her berth in the creek went smoothly. The tug pulled the bow gently to port to counteract the propeller torque and a small crowd waved good bye from the bank. The Detroit warmed up and settled into a steady beat.

In the waterway we cast the tug off. I put the helm over and opened the throttle. A plume of black smoke poured out the exhaust and water swirled from the stern. The tug tooted and bustled back up the creek. We were underway.

We passed tinnies full of old boys out fishing. As soon as the rusty black ship appeared up the canal, they began frantically pulling on outboard start-cords to get out of our way. A couple of Dougie’s mates steamed along on our quarter in their shrimp boats, then waved, tooted and headed back.

Oil pressures and temperature looked good on the gauges and everything seemed to be working well belowdecks. The boys crowded in the wheelhouse, popping the tops off beer cans and talking excitedly.

My knees stopped trembling.

A VHF call to our first bridge operator produced the desired effect. Lights started flashing, alarm bells rang and barrier arms dropped across the road. The traffic ground to a halt while people tooted their horns, flashed headlights and waved.

The next bridge was a fixed model and we slowed the General to bare steerage speed. I scrambled onto the ‘monkey island’ on top of the wheelhouse and held my breath as we slid below the bridge with about half a metre to spare – and likewise the sides, which had about 30cm clearance between them and the concrete pylons holding the bridge up.

Sweat streamed down Dougie’s face as he sat behind the wheel, turning it a few centimetres in either direction.

“Goddamn it Lenzee,” the normally imperturbable Dougie said, “I thought we was gonna break the bank on that one.”

That’d look good, I thought, taking out one of the US Government’s bridges while operating an unregistered ship without any qualifications after spending four years in the country working on a six-month tourist visa. Yessir….that’d be enough for them to lock me up with the mass murderers and drug smugglers and chuck the key away!

More bridges passed by, some opening, some not, with varying degrees of clearance. By sticking to the outside of the bends we had enough water depth to get by and the Detroit rumbled on imperturbedly.

Just on dusk we pulled into the wharf at Jacksonville, the big ol’ river winding slowly past the General, rippling against her rusty topsides.

Herein lay the biggest problem. At high water there was about 6m between our deck and the wharf below – but there was nobody there to take our mooring lines. We idled the ship’s shoulder against the wharf and called the port control. No – no help there. We hadn’t told them we were coming, so they had all gone home.

And our own crew had too many Butt-wipers on board or were too fat to do much about it.

Finally I lowered a line over the side, slid down to the wharf and took a bow line, spring line and stern line to slip them on the bollards.

“Here ya go,” Dougie stuffed a roll of cash in my hand. “You wanna go scallopin?” BNZ