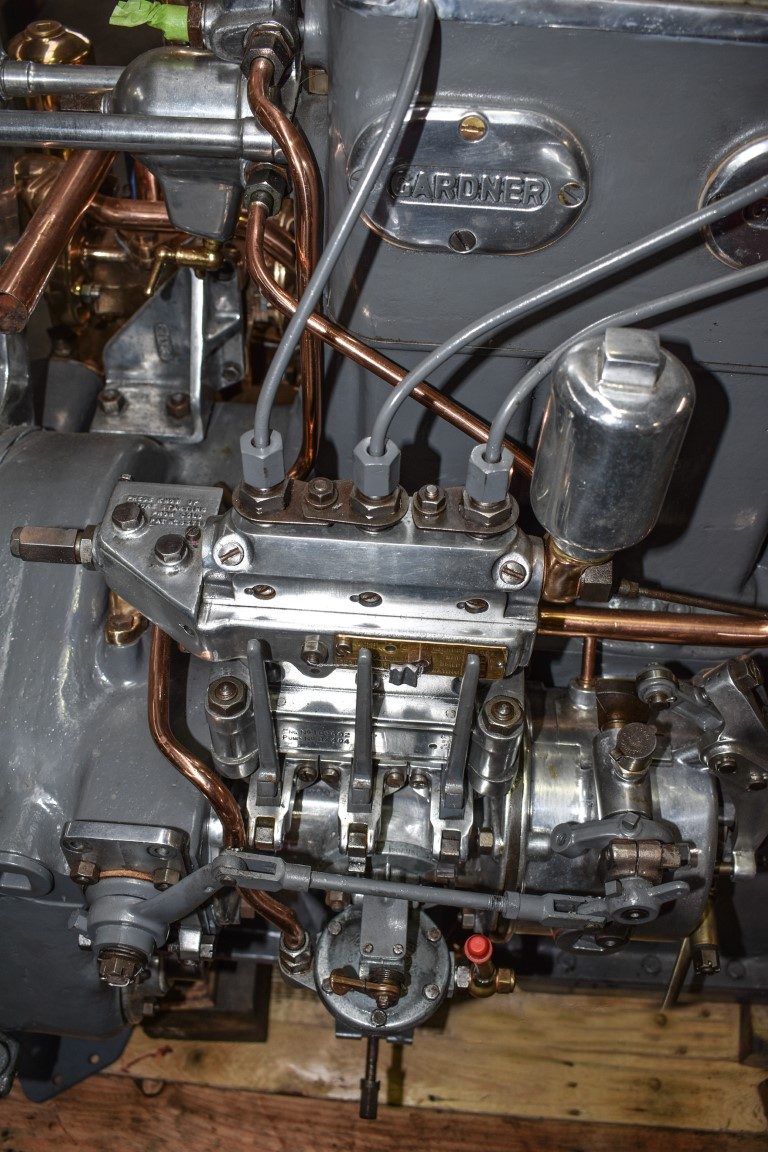

Chances are that the noisy lump of metal which keeps your crank spinning, and your boat moving, is a trusty diesel, writes Lindsay Wright.

The crank in question is the crankshaft, a concentric cast metal shaft running through the bottom of your internal combustion engine.

As it spins, the pistons which are clamped to it rise and fall within their cylinders. On the up strokes they compress a fuel/air mixture in the combustion chamber which explodes and drives the piston down to spin the crank which spins the cogs in your gearbox which, in turn, spins the propeller.

The big difference between petrol and diesel power is the means of igniting the compressed air/fuel mixture in the combustion chamber.

Petrol engines take a small zap of electricity from the battery, enhance it in the coil and apportion it to individual cylinders using a distributor. In the cylinders, sparking plugs create a small flash which ignites the air/fuel to drive the piston downwards.

The trusty old diesel however, needs no unpredictable electronic gizmos.

The compressed charge of fuel and air super heats (to about 600°C) and explodes, driving the piston down to spin the crank.

Petrol engines are lighter, arguably smoother and quieter.

The opinionated authoress of a cruising book once tried to make a case for fitting petrol engines in yachts – she had probably never seen a boat blown to smithereens by a petrol explosion or helped pull the boat’s badly burned and temporarily blinded occupant out of the water.

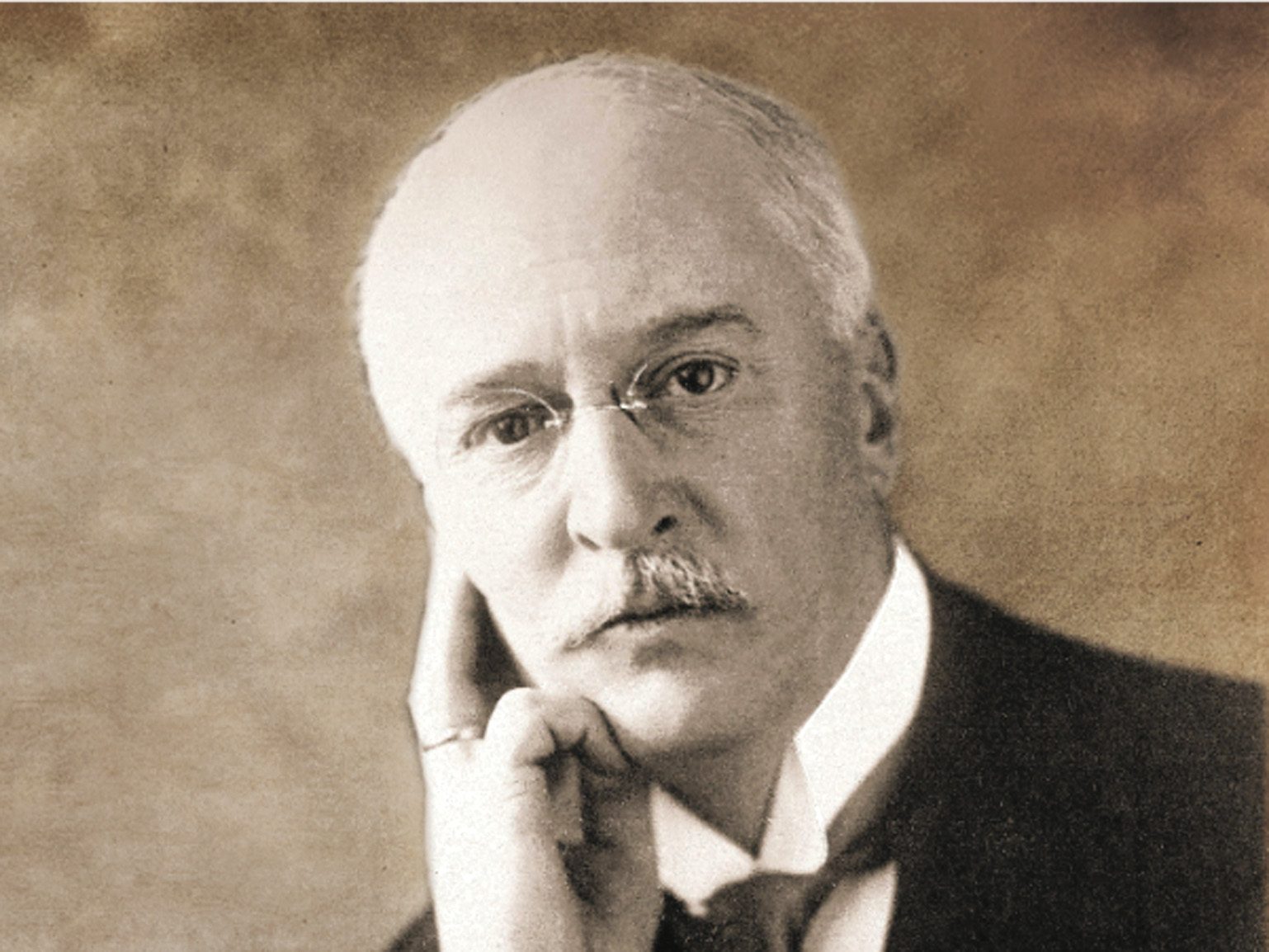

German engineer Nicholas Otto created the first petrol engine in 1876. It had a thermal efficiency of 20% – or twice that of the steam engines it replaced. But Otto’s compatriot, Herr Rudolf Christian Diesel, decided he could take the engine to the next level.

Diesel was born in Paris to German parents and began his career working in their leather workshop, making deliveries with a hand cart. When the Franco–German war started in 1870, his family was forced to move to London. Young Rudy was despatched to live with an uncle in Augsburg, who was a mathematics teacher. Under his uncle’s tutelage, he topped his class at the Royal Bavarian Polytech, then spent a year working in Switzerland before returning to Paris and establishing a refrigeration company with his old professor.

Next he was recruited to manage the R&D programme for a major engineering firm, a position which came with the delightful designation: Thermodynamilforssdirektorgeneral. Try saying that in a hurry!

Diesel was developing high pressure engines fuelled by ammonia when one blew up and left him with lifelong health and eyesight problems.

However his Swiss contacts realised the potential of what he was working on and helped fund his research.

So, 21 years after the first petrol engine rattled round, Diesel unveiled his first compression ignition engine which is still on display at the Munich Technical Museum.

The modern diesel was born.

Diesel claimed that the engine was more efficient than a petrol one because, without a spark plug, it relied on the fuel to explode from the heat generated by higher cylinder pressure.

Diesel engines were slower revving and had to be of heavier and stronger construction to withstand the extra pressure. But Diesel’s engine showed a thermal efficiency of 26.2% – much better than a petrol equivalent.

The new engine was a hit with ship owners and industrialists – able to run on gravity-fed fuel, it quickly put the gangs of stokers shovelling coal, which steam engines needed, out of business.

Because of their economy, and the fuel’s low flammability, diesel engines were soon pressed into service in airships.

By the late 1920s diesel-powered passenger planes were flying – the first was a Packard DR980 air-cooled radial, but Junkers soon came out with the Jumo 205 model.

There was even a brief resurgence in diesel aero engines in 2010.

But it was said that the new diesels had been rushed onto the market too quickly, some customers found them unreliable and demanded refunds.

With his business sliding towards insolvency, despite the widespread uptake of his new engines, the ingenious inventor had a nervous breakdown.

In 1904, when most submarines were powered by, amazingly, steam engines, the French began using diesel engines for their undersea warships.

The British had only started building subs in 1900 and persisted with steam propulsion. “The most fatal error ever imaginable is to put steam engines in submarines,” Jacky Fisher, father of HMS Dreadnought and founder of the modern Navy, protested. But he was not a Sea Lord at the time and was outvoted.

But others could see sense and sided with Fisher who had planned to build a new range of diesel-powered subs. Diesel was invited to England to discuss the matter.

Meanwhile, the German navy had beaten them to it and was using diesels in its U-boats. They wanted exclusive rights, but Diesel refused. The world was beginning to recognise the huge potential of the new engine for their most important industries. Diesel had already sold the US patents to brewing baron, Anheuser Busch, to use in its breweries.

And the British latterly decided they wanted exclusive rights to the diesel engine for their warships, surface and underwater.

On 29th September Diesel packed his bags and left in the steamer Dresden for Harwich to negotiate with the Royal Navy brass.

Crewmembers who went to wake him at 6:15am found his bed empty and unslept in. A neatly folded overcoat was found on deck. His body was found a week or so later by a Dutch boat whose crew emptied his pockets but left the decomposing body in the water.

Diesel was reputed to have made millions from royalties for his engines, but his bank accounts had been emptied. But he had given his wife a suitcase before he left, with instructions that she open it a week later. When opened, the suitcase was found to contain over a million dollars.

Foul play was suspected with Big Coal and the German navy among the most likely villains.

But WWI started 11 months later and diesel-powered submarines played a large part in Germany’s plan to block transatlantic trade and starve Britain into submission. Thence, they had an interest in seeing the Royal Navy stuck with steam-powered submarines.

Diesel never lived to see millions of his engines built to power boats, vehicles, machinery and society as we know it.

But Herr Diesel’s robust and reliable engines may have had their day in the engine room. Most European automotive manufacturers have announced plans to discontinue building diesels and a new age of propulsion looks set to arrive. The boats of the future will likely be powered by electricity or hydrogen.