In the high-stakes world of model powerboat racing there’s no substitute for cunning and skulduggery – but sometimes a little honour prevails. By Gerard Richards.

Mairangi Bay, on Auckland’s North Shore, was a cool place to be as a mid-teen in 1972.

Simpler, more innocent times to be sure, hanging out with my mates. Bicycles and slot car racing were big attractions, but the beach was a mecca for our pimple-infested crew.

Striving to look groovy in our Hang Ten and Ocean Pacific gear, we soaked up too much sun while surreptitiously ogling the bikini-clad babes. But as tongue-tied, monosyllabic young males, we never made any moves.

Winter was different. With a sparsely-populated beach, model powerboat racing was the go for three winters from 1970-72. The catalyst for this was one of the key characters in our tribe, Kevin Jose.

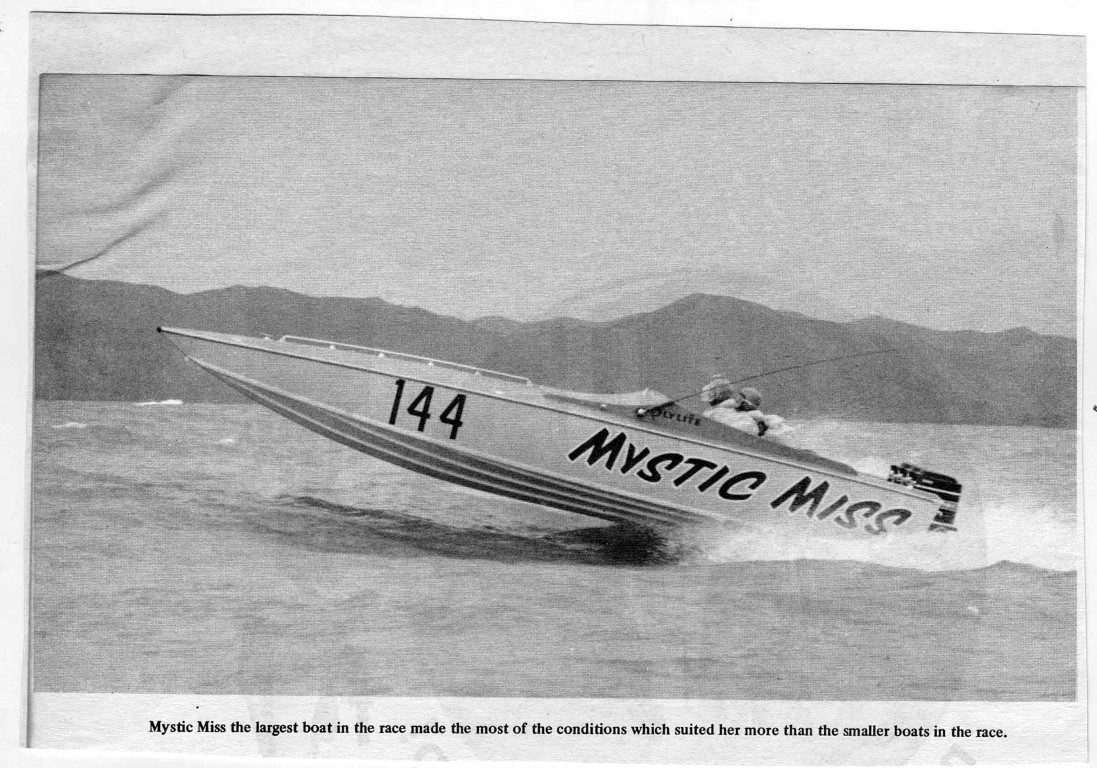

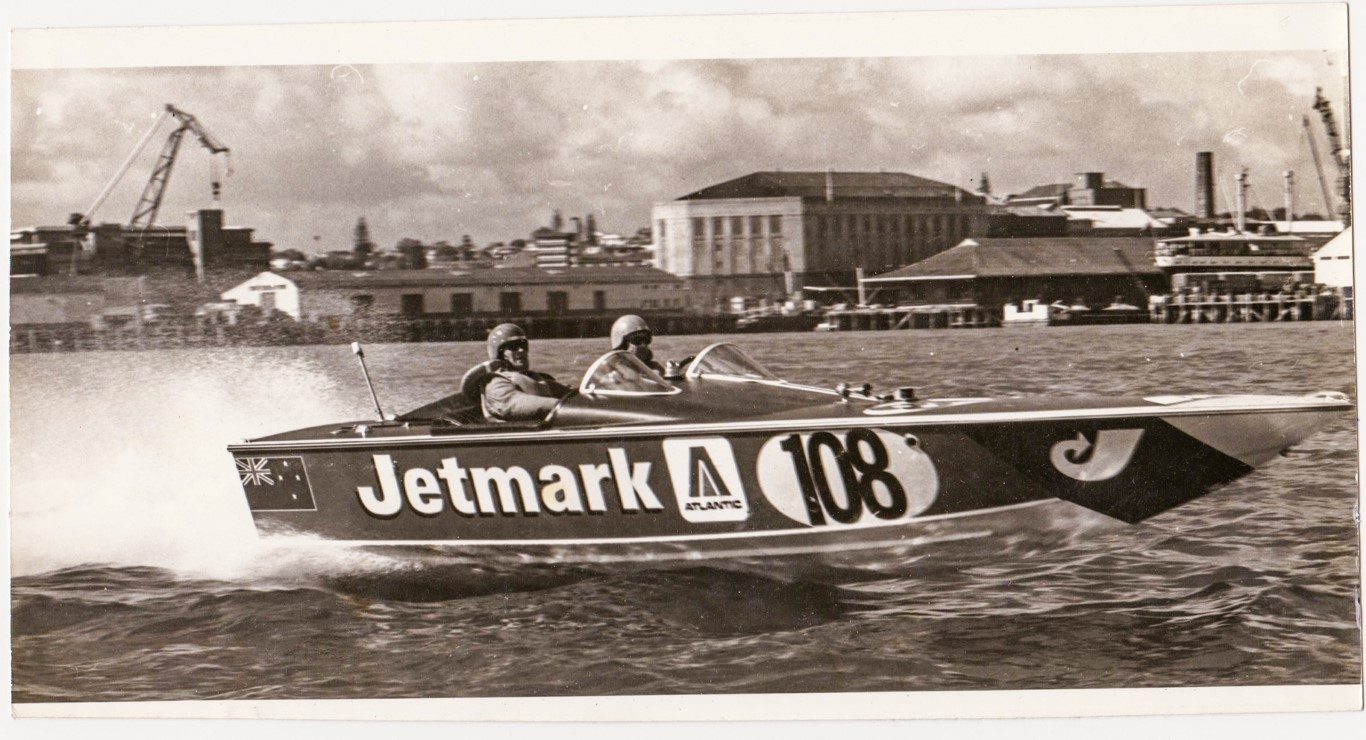

He press-ganged us to bike down to Devonport in 1970 to watch the Auckland Offshore Powerboat Races, the Atlantic 100 (to Kawau Island and back) and the Atlantic Six-hour Marathon (held in Auckland’s inner harbour). ‘Atlantic’ was a fuel/oil brand now long defunct. Those thundering Chev V8 inboards and screaming Mercury 135s blew us away. Tara Too and Jetmark made a blinding impression, along with Mystic Miss’ triple-rig 135hp Mercs.

In a bid to replicate this on a miniature scale (under Kevin’s lead), we crunched out the format for the first model-boat ‘championship’. And we had a perfect racing venue – sort of. Between Mairangi Bay and Murray’s Bay was a concrete storm water pipe. It trapped a pond of calm water – between the pipes and the cliff. Perfect for the drag boat racing.

No fancy radio control stuff – even if it were available it would have been laughingly unaffordable. There was one problem though: with up to four boats starting abreast, only one person could start from pole – next to the concrete walkway, a decided advantage in managing the boat’s direction.

The rest of us had to stumble over rocks in the pool to keep up with our boats, many of which were directionally-challenged. Often a slower boat would retire after being swamped in the wake from a faster boat.

Around 1970 the local model powerboat kitset scene was fairly basic. There was a balsa model – a traditional 1940s/50s classic launch/runabout style with two hatches. In 1970 this was about as sexy as racing a tugboat – sleek it was not.

Another offering was a plastic runabout with outboard, a local brand – RSL Classic. I acquired one of the prehistoric balsa runabouts and fitted it with a slot car motor, but the weight of the batteries defeated any speed gain and its barge-like bulk did the rest. It quickly became apparent that if you were serious about winning this championship, the way forward involved designing and building your own boat.

Another offering was a plastic runabout with outboard, a local brand – RSL Classic. I acquired one of the prehistoric balsa runabouts and fitted it with a slot car motor, but the weight of the batteries defeated any speed gain and its barge-like bulk did the rest. It quickly became apparent that if you were serious about winning this championship, the way forward involved designing and building your own boat.

KING KEVIN

Kevin was fastest out of the gate with a self-built boat that ticked all the boxes. Light, sleek and wellbalanced, it did the business handsomely with him winning the 16-race series easily. We were literally floundering in his wake.

I attempted to fabricate my own creation. Shocking. It had no frame or curves and was always on the verge of sinking. But it was a lot faster and did score a couple of wins which elevated me to second overall.

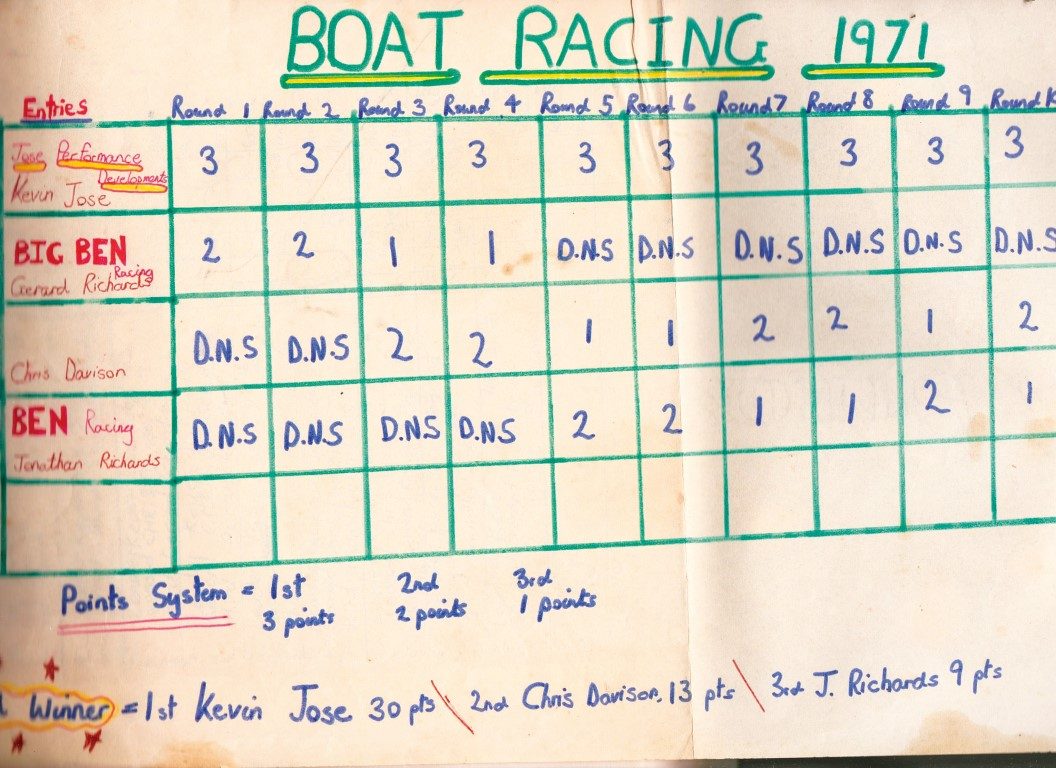

Kevin again dominated the ’71 series, warding off challenges from my brother Jonathan and arch-rival Chris Davison. I’d have to build a new boat.

The 1972 series turned out to be the best (and unbeknown to us at the time, also the last). Aftermarket, locally-made model powerboat accessories – brass prop shafts, props and rudders – were readily available. Mabuchi motors were the hot performers, particularly the F6 and RE36.

I designed and built my boat early. It sported a flat-vee bottom with a generous beam to ensure it would plane. The bow curves were quite extreme, which necessitated pinning the cladding in small sections at a time.

Going from a boat with no curves to this beauty was a perverse challenge for a raw recruit, hoping to go from zero to hero. It was also designed to run an outboard motor I’d scored when I won a prize for my RSL Classic NZ-made plastic runabout kit – a model-making competition at the legendary Max Patterson’s Stationers and Toyshop in Mairangi Bay.

Initially the outboard seemed promising – it made a lot of noise which suggested power and speed. Alas it flattered to deceive – all show and not much go. Chris’ masterstroke was a beautifully-built twin inboard creation. As ever, Kevin produced a small, well-balanced boat that arrived at the first of the ’72 races tuned, tested and ready to go. My brother Jonathan also had a very hot F6 Mabuchi inboard-powered boat.

But Chris, despite having finished his boat only the day before, absolutely blitzed the field in the opening weekend’s two races. Fortunately for us (but not for him) he never managed to get his super weapon to repeat the dose. The motors refused to run in sync, and he was eventually forced to convert to a single motor. In his large boat this wasn’t a formula for success.

My brother Jonathan picked up the mantle, duking it out with Kevin until the turning point of the series, the controversial (and, in his case, unlucky) Race 13. At that stage he had 25 points to Kevin’s 27. Chris and I were languishing on 9 and 5 points respectively. My ailing outboard motor had been dismal, only good for 3rd places, before expiring completely.

With things delicately-balanced between Kevin and Jonathan, matters descended into conflict and acrimony. Kevin and Chris (not obvious allies) slapped an America’s Cup-style penalty on my brother for a supposed unpaid entry fee infringement, and immediately confiscated eight of his points, reducing his tally to 17. In disgust Jonathan (who had the fastest boat at this point) withdrew from the series.

Chris appeared with a new, smaller boat after missing four races – the scenario pretty much ensured Kevin won the title again. To say I was pissed-off with these underhand tactics was an understatement. Something had to be done to counter this miscarriage of justice. Brotherly honour was at stake!

OUTBOARD TO INBOARD

Desperate times require desperate action and to get my boat back into the action I converted it to inboard power.

The boat’s dimensions and layout were perfect, and I had the use of a hot F6 Mabuchi motor my brother no longer needed after his sudden departure.

With the new motor the boat flew – I was back in the fast lane. I won the next four races and only lost another through an engine wire being connected the wrong way (the boat went in reverse!) But fortune’s a fickle mistress. The boat lost its edge in the last few races. Maybe I was complacent, or perhaps the gear got tired. Chris won most of the remaining races, with me second and Kevin a lacklustre 3rd place in the last eight races.

But Kevin already had it in the bag. The end of term report for ’72 saw him crowned Champ once again, with Chris second and me a disappointing 3rd. This result – and the legacy of the mid-season hijack of brother’s strong campaign – left a sourness in the mouth.

72 – as I came to refer to the boat – was still pretty rough at the end of the 1972 series. I’d planned to finish the top sides and have another go for the ’73 series, but that never eventuated. It was the end of the road for model powerboat racing. Life was going in other directions.

I tossed the boat aside for a few years (fortunately not in the rubbish). In 1975, I began a restoration which progressed but then stalled. Life got in the way again. It returned to its storage box. I only completed the refurb and repaint around 1988. But it was a static exhibit. The F6 motor was dead.

RE-MATCH

Fast forward to late 2002 when, out of left field my old mate Kevin suggested a re-match. We would build new model powerboats, as before – with no radio-control bullshit – and have a SHOWDOWN!

We agreed on a single motor – a Mabuchi RE280 – driving the same prop shaft and prop. Hull design was completely open. We both began construction in early 2003, closely guarding our designs. The venue would be Kevin’s home swimming pool.

I named my boat Mary-Anne after my partner. It was modelled on the early 70s offshore race boats and had a relatively deep vee, flattening out at the rear. I’d hoped it would plane well, but it wallowed hideously and was comprehensively outgunned by the old enemy. I lost the series 9-0 and was smarting. Kevin had stolen a completely legal march on me by constructing a partial hydroplane – absolutely in the spirit of the open rules.

To restore some pride I thought about building another boat, but time was against me. Then my eye fell on 72 displayed in my Man Cave. Why not? The dimensions were still perfect and the flat slightly curving concave bottom of the hull, would provide a degree of tunnel effect.

I called up the old foe and issued a challenge: I wanted a rematch of the re-match. He agreed, probably thinking he’d serve another thrashing with his hydro The Peglar Racer. I rebuilt the old boat again, with the RE280 motor, a new rudder and some structural refurbs. The original prop shaft and prop remained. The topside hatches were slightly modified and lightweight batteries fitted.

I called up the old foe and issued a challenge: I wanted a rematch of the re-match. He agreed, probably thinking he’d serve another thrashing with his hydro The Peglar Racer. I rebuilt the old boat again, with the RE280 motor, a new rudder and some structural refurbs. The original prop shaft and prop remained. The topside hatches were slightly modified and lightweight batteries fitted.

As the old saying goes, “When the flag drops the bullshit stops!” Second re-match race day 2003 saw ballistically close racing. The two boats were neck and neck all afternoon. Kevin won the first few races narrowly, but then 72 – on new batteries – hammered home a series of narrow victories over the old enemy. Later in the day Kevin regrouped, changing a slipping engine coupling, and when my batteries began to fade, he won the last few races.

Once again it went down to the wire, with Kevin just edging me (yet again!) in race wins, but honour had prevailed. After 31 years, 72 had returned to the winner’s circle.

Today, the illustrious 72 has pride of place on my shelf, displaying its 50-year legacy and ready to return to the water at a moment’s notice! There’s something special about a survivor race boat that one made in their boyhood and is still almost completely original.

A time-tunnel back to the golden days of carefree youth.