McDonnell turns 70 next year – but you’d never guess it. Sure, the hair’s a whiter shade of pale and the face speaks of experiences good and bad, but the lively demeanor, sparkling eyes and rapid-fire conversation belong to a much younger soul.

And though he might be 40 years older than most of his colleagues at Auckland’s Rocket Lab, he feels perfectly at home. Retirement is definitely not part of his mindset: “I love it – I bet I could work here until I’m 80!”

McDonnell is a vastly-experienced composite technician and works in the team building components used in Rocket Lab’s three-stage, carbon-fibre Electron rockets. And, he says, it’s not as bizarre a career leap as it might sound. “There’s a whole lot of similarities building race boats and rockets – it all comes down to laying up the base material correctly and curing it properly.”

He’s the first to admit that his improbable switch to rocket building (he joined the company in February this year) was a function of fate – like so much of his life story. And to understand that, you need to start at the beginning.

Born in Auckland, McDonnell grew up sailing P Class dinghies and after leaving school decided to pursue boatbuilding. He joined Chris Robertson’s Greenhithe boatyard but the holiday job involved pounding rivets. It didn’t ignite any passion and he quickly switched to a five-year sailmaking apprenticeship at Chris Bouzaid’s Sails & Covers.

But his inventive mind kept straying to boatbuilding – and when the (then) futuristic fibreglass material emerged, he was quick to embrace it. “At 16 I was sailing an International Moth – a big ‘development’ class. It had to be 11-feet long and carry 90 square feet of sail – but other than that you could do whatever the hell you wanted.

“So I designed and built an ultra-light Moth. I opted for a scow, because a flat bottom really takes off on a reach. I set up the frames in my dad’s basement, nailed some foam to them and glassed it over. Dad showed me how to mix the resin – but I really didn’t have a clue what I was doing. I skimped on everything.”

At the next Bucklands Beach regatta he promptly won the first race, followed by second, third and fourth in the subsequent three races. And then the boat fell apart – it was far too weak and light. But that foray into fibreglass kindled a life-long interest in composite construction.

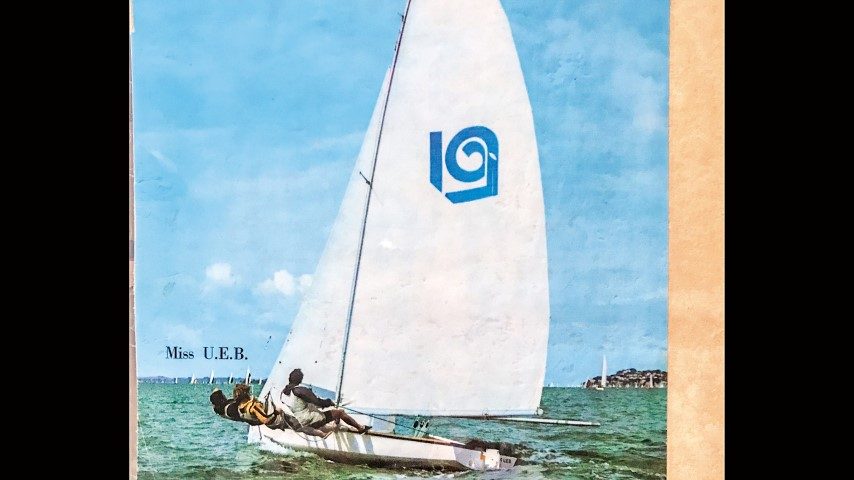

Soon he was sailing competitively in the 18-foot skiff class and represented New Zealand in the 1971 Worlds in Auckland, sailing a boat called Miss UEB (sponsored by United Empire Box). She was a little unusual with her three-man crew – most skiffs carried four.

“Bruce Farr designed and built our boat – in plywood – in his mother’s basement in Devonport. He said it would be faster as a three-hander – lighter with smaller sails, and one less trapeze. And he was right – we came second – we should’ve won.”

His sailmaking apprenticeship completed, McDonnell left for California in 1971 to represent New Zealand in the 18-foot skiffs regatta at the Long Beach Sea Festival. Once again, fate presented a crossroad. “I met a lady – she came back to New Zealand with me – we got married and went back to the US for an OE, and never came back.”

Instead, he established a sail loft in San Diego – right next door to North Sails – manufacturing dacron sails, and it prospered.

Boatbuilder

The decision to switch to boatbuilding was sown over a round of golf with a friend in San Diego – McDonnell wryly points out that many of life’s most serious, trajectory-altering decisions are made on a golf course.

“He insisted I should try boatbuilding. So I sold my share in the loft to my partner and began boatbuilding – and enjoyed it straightaway. Back in the 70s there were no computers – we lofted the boats full-size on the floor. I lofted a lot of racing boats – all fibreglass/balsa core hulls.”

And then, by chance, he met Dennis Connor – and entered the frenetic scrum that is the America’s Cup.

McDonnell would go on to work with nine America’s Cup campaigns – six with Connor’s Stars & Stripes team, two with Alinghi and, in 2013, a final one with Artemis. He also worked with three round-the-world campaigns. Over the years, he was drawn ever more deeply into the emerging, esoteric world of composites.

His time with Connor and Stars & Stripes included the infamous Cat vs Big Boat duel in 1988. “We had a wing sail on the catamaran – it’s not as new an invention as some would believe! The ribs for the wing sails were carbon-fibre. They were built by some high-tech aerospace company in the Mojave Desert, but crucially, I had to learn how to repair the ribs when they got damaged.”

The bizarre thing about the Cat vs Big Boat challenge, he says, is how it transformed the America’s Cup. “The event was so controversial and litigious – more in the court room than on the water – I was convinced that would be the end of it. The America’s Cup would cease to exist.

“But then they bought in a new rule that re-galvanised it all – and over 100 boats were built by various syndicates – and with that rejuvenation came major advances in composite design and construction. For me, it was simply about acquiring a new skill at the cutting edge of yacht racing. As is so often the Kiwi way – I kind of winged it – it evolved and I followed.”

Rocket Lab

Having been immersed in boatbuilding and America’s Cup campaigns for more years than he cares to remember, McDonnell decided it was finally time to come home.

Part of the process was introducing New Zealand to his American wife – to check that she’d be happy living here. A whistle-stop tour around the entire country received a happy thumb’s up. During that tour fate intervened once again.

“I met an old friend along the way and he asked what I planned to do next. It ended with him suggesting I contact Rocket Lab. A few weeks later, another sailmaking friend offered the same advice and then, at a family wedding, one of guests repeated it. Bugger it, I thought, I’ll give them a call.”

At the interview (the day before his scheduled return to the US), the recruiter asked if he could start the next day. That was a little too fast – but it cemented McDonnell’s decision to join the team.

“I love coming to work every day. I do 50 hours a week here and get weekends off – compared to a Cup campaign, that’s a holiday! And it is very similar to boatbuilding – which is why so many of the staff here are ex-America’s Cup boatbuilding guys.”

Despite the years of experience, McDonnel stresses he is not a composite guru or expert. “Today, the actual composite design is done on computers by the ‘smart’ guys. They figure out where and how to use the material – where to add strength, where to cut back on the layers.

“Most of the carbon-fibre I work with is pre-preg – it already has the resin in it. The designers regulate the amount of resin that’s used – very precisely. We follow the plan, lay it up, vacuum bag it and then stick it in the oven.”

Perhaps the most important part of McDonnell’s story is hope and encouragement.

“People will look at me and ask what’s an old bugger like you doing here? Well, I’d say, I hopefully offer similar old buggers some inspiration – and there are many of us out there. My message is this: if you’ve got your health, have a little energy and like meeting new people – don’t give up. Life takes you in different – and sometimes odd – directions, but you can make your own destiny as well.”

Like the rockets he builds, he has one other shoot-for-the-stars ambition. “I plan to compete in the 100m event for 100-year olds. Not only participate, but also set the world record! I’ve been inspired by the old lady who did a similar thing. I know I can do it.” And he probably will.

Retirement might not be a word in McDonnell’s current vocabulary, but he has now got that bach on the beach. Where he can launch his dinghy and go sailing. Just like in the old days.