The customs officer at Hobart airport eyed the little wooden box warily – like it contained five klios of cocaine or half a dozen hand grenades. “What did you say it is?” he drawled.

“It’s a sextant – for navigation,” I replied.

It was too big a decision to make on his own, so he summoned two workmates who pulled the foam padding from the box and x-rayed it, examined the box for false bottoms and ordered me to demonstrate how to use it.

Eventually they decided that my harmless old sextant posed no danger to Australian homeland security and waved me on. At first I thought their attitude was due to lack of education but then, maybe, the sextant is just hopelessly archaic and many people would have the same response. Like traditional boatbuilding skills, maybe traditional navigating and seamanship skills are also in danger of disappearing altogether.

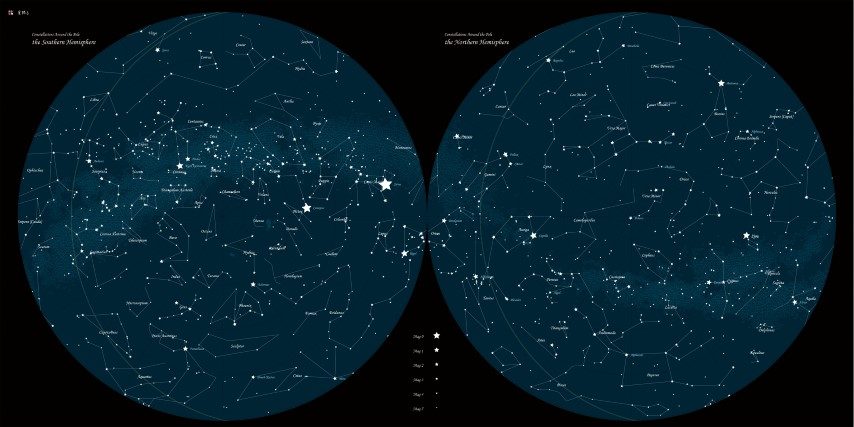

A sextant is a seafarer’s last connection with celestial bodies that wheel through the skies at night. Polynesian navigators, bird species and others use the sun, moon and stars to help them reach their destinations – whether they be nests a few metres away or breeding grounds on the other side of the planet.

Various tools were developed to enable mariners to measure the angle between themselves and astronomical bodies to derive their latitude. The astrolabe, back-staff and cross-staff were tried and discarded because they were too inaccurate or cumbersome for use at sea. Sir Isaac Newton came up with a workable design and his plans were shown to the Royal Society in 1699.

The sextant uses a principle of double reflection so an observer can simultaneously see the horizon and a selected heavenly body and measure the angular distance between them with some accuracy. An added bonus is that a sextant can be used on any plane – such as between two landmarks to gain a distance off.

John Haadley (1862 – 1744) came up with two designs close to Newton’s and an American, Thomas Godfrey, independently came up with a similar design at the same time. And their basic designs were so good that they remained the instrument of choice for Western seafarers for the next 200 years. Fletcher Christian was badly burned in a vain attempt to retrieve the sextant from the great cabin of HMS Bounty while she burned at Bounty Bay, Pitcairn Island. “Without it – we are truly lost,” he lamented.

Thousands of people have worked hard to learn the principles and practice of celestial navigation but now most sailors rely, almost exclusively, on electronic aids to navigation. But reading numbers off a little green display is a thin, prosaic substitute for the practice of celestial navigation – for being a navigator.

There is something magical about locating yourself on the face of the earth in relation to the rest of the universe. Every landfall is a triumph – something you made happen. GPS replaces the need to pay attention to your surroundings and distances us from the natural world. Good celestial navigators develop an intuition. GPS weakens our ability to find our way by our senses whereas celestial navigation extends our skills and heightens our relationship with the world around us.

Perhaps the greatest feat in Western navigation was the voyage of the 7.2m converted lifeboat, James Caird, which was navigated 800nm across the Southern Ocean by New Zealander Frank Worsley in 1914. Perpetually wet and near frozen, and with rare sextant sightings of the sun in the cloudy conditions, Worsley took Ernest Shackleton and four other crew from Elephant Island to the west coast of South Georgia.

Using a sextant is to join generations of seafarers and, like traditional boats which are built for beauty and seaworthiness rather than the number of berths and toilets they contain, are experiencing greater interest, so too should the arts of the celestial navigator.

Good celestial navigation depends on maintaining scrupulous DR (dead reckoning) – an ongoing chore which GPS users may find onerous, and regularly fixing positions on a paper chart. I’ve heard about an American yacht which paid for a RNZAF Orion to fly over its position and radio a position to them because its GPS had malfunctioned and the crew hadn’t maintained a plot.

A good quality sextant fits the hand like a glove and provides a lot of satisfaction from its use – like any good tool. My own old Tamaya is 38 years old and I still get a lot of pleasure from handling it. A position line (LOP) from a sextant with a GPS position located on it can still swell my head like a helium balloon.

I once met an Englishman who collected sextants and had 27 on board – one for whatever conditions he thought would best suit it.

And if your sextant needs a birthday there is a company in Auckland which resilvers mirrors and any other repair work. Otherwise they’re maintenance-free with maybe a wash down with fresh water if they get salt spray on them.

Over the years sextants have been made from bronze, steel, low-expansion aluminium or brass, ceramics and plastic.

Some people in the tropics like to keep their sextants in a box on deck so that they’re at ambient temperature and there’s no expansion when it comes to use them. Ebco (UK) or Davis (USA) both made black plastic sextants which got decidedly wobbly if you had to spend time on deck waiting for a noon sight. Ebco went out of business and Davis changed colours.

Some people in the tropics like to keep their sextants in a box on deck so that they’re at ambient temperature and there’s no expansion when it comes to use them. Ebco (UK) or Davis (USA) both made black plastic sextants which got decidedly wobbly if you had to spend time on deck waiting for a noon sight. Ebco went out of business and Davis changed colours.

Probably the most common yacht sextant is a white Freiberger yachtsman, a high-quality German-built instrument which is a delight to handle. It sells for about $500 on Trade Me. Plastic sextants sell for much less.

It also pays to have a sextant with a good range of filters. Most yacht sextants are designed for the tropics and the filters are too dark to locate whatever you want to take a sight of, at sub-tropical latitudes.

It pays to have a lighter sextant because you may need to spend 20 minutes or longer on deck to get a meridian altitude at local noon; tracking the sun as it rises then finally stops due north or south of your position. Heavy old sextants like a Hughes can make your arms tremble as you hold them up to track the sun’s ascent.

Before using the sextant set the Vernier to 0 degrees – then sight through the eyepiece to the horizon. It should line up but, if it doesn’t, any difference between your reading and 0 is index error and should be applied to later observations.

Older nautical almanacs had a table in the back which gave distance off a fixed object by vertical sextant angle. Navigators could take the height of, say, a mountain off the chart, obtain a sextant angle on it, and the tabulated distance off for that angle could be taken from the table. Take a compass bearing on the object and you are on that bearing at the specified distance off.

All great fun.

The classic text to learn from is Mary Blewitt’s Ocean Yacht Navigation (Mary Blewitt is a nom de plume used by a British navy officer) but I prefer Blue Water Yacht Navigation by Craig Coutts because he’s from the same hemisphere that we are.

Many well-known Kiwi yacht navigators have left on an offshore cruise with either of those books and learned to use the sextant en route. After all – you only need to know exactly where you are when you’re about to make landfall.

In 1973 the USAF had brought the GPS system on-line. Although it wasn’t the first satellite-derived position fixing system it was, by far, the most sophisticated. Engineers designed and built more than 24 satellites each carrying an atomic clock which was carefully shielded from cosmic radiation. Each satellite was delivered to a carefully calibrated orbit by rocket. The satellites transmit very precise information about their location in space and a time signal accurate to nanoseconds.

By comparing signals from four or more satellites, a GPS receiver anywhere on earth can fix its position to within a few metres, plus its speed and elevation.

This system began operating in the early 1980s but didn’t become fully operational until the mid-1990s. It’s reputed to have cost the US Government $US12 billion to develop and maintenance is expensive – but the system was generously made available to users worldwide in 1983.

But the US military kept the most accurate version for their own use until May 2000 when the administration stopped the “selective availability” system and made the data available to all.

A GPS fix is, essentially, derived from four satellites with the signals collated by a receiver’s computer algorithms – not unlike a four-star fix worked out by someone with a sextant, almanac and sight reduction tables.

The difference is that the weak signals from GPS satellites are easily blocked as has happened with heavy vehicle drivers in Europe with GPS trackers fitted to their trucks. They jam the signals to conceal from their employers exactly where they have been – inadvertently blocking GPS coverage in the surrounding area.

Russia and Europe have both developed satellite navigation systems of their own to use in the likelihood that the US system falls over – or is withdrawn.

In that event, many of us will just be able to reach for our sextants.