The 830-mile passage from Panama to the Galapagos – the most direct way home for Kiwi circumnavigators or Kiwis coming over from Europe – has a reputation among cruisers as fluky and frustrating.

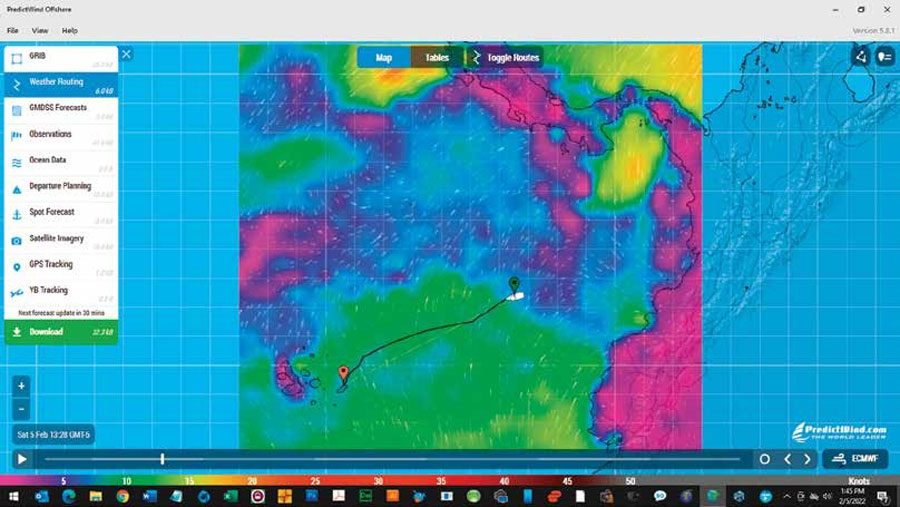

Hearing the murmurs, Harriet and I asked for a weather forecast for our Dolphin 460 cat, OCEAN, from Commanders’ Weather, a passage-routing service we’ve been using for the past 10 years. The meteorologists replied with a picture of, well, a whole lot of stuff going on in this pocket of the Pacific. Along our route we’d also be downloading weather GRIBs from PredictWind; the updates are easy, and the weather-routing simulations help us grasp the dynamics of ocean weather.

This passage is likely to be a mash-up of three parts, though the weather elements of each part can expand, contract, intensify, or fizzle out – this is what happens when weather elements meet and mix. In part one of the passage, boats departing Panama generally get about a day’s worth of tailwinds as the Caribbean’s northeast trade winds pass over Panama and fan out into the Pacific. Because their consistency is compromised by their overland journey, these winds are variable in strength and direction. Then, in part two, the battle of the winds begins: the calms and squalls of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) wander drunkenly about in a zone hundreds of miles wide between the northeast trade winds and the southeast trade winds. Finally, in the third and longest leg of the passage, about 500 miles, cruisers often face 10- to 20-knot headwinds and chop from the southwest. And the currents of this passage are variable, too. Does this sound tricky to predict? It is.

DAY ONE. A good start! OCEAN, heading 190°T, is making about 6 knots under screecher on starboard tack in light northerly winds. We are getting a sampling of the freaky currents in the Gulf of Panama, sailing through six distinct current lines which almost seem to sizzle, the flat patch after each line feeling like it is lower than the previous patch. Weird.

We are following the strategy suggested by Commanders’ Weather to get south into steadier winds and set ourselves up to windward on the long port tack to the Galapagos. With over 800 miles to go, we are sailing 40°away from the 230°T rhumbline to the Galapagos, which takes some intestinal fortitude for Harriet and me. We are both ex-racers, and we’d rather head at the mark (in this case, the island of San Cristobal) than head toward a corner of the ‘racecourse.’ But we’ve been though the ITCZ years before elsewhere – the zone is slow, frustrating going – and we accept that this end-around is necessary. But how far out to the corner should we go? How do we know when to tack over for the Galapagos? How do you determine a layline from 550 miles away? No sign of the ITCZ yet. Soon we are motoring in flat seas, only a couple of knots of wind, the sky crowded with stars, the Northern Hemisphere’s Big Dipper astern.

DAY TWO. Now the wind, still light, has shifted forward into the south. It’s too early for the southeast trades. Is this the beginning of some ITCZ weirdness? Through no brilliance of our own, we are getting a 1.5-knot favorable current boost to the south. OCEAN is motoring under mainsail alone at 6 knots on one engine, making 7.5 knots speed over ground. The sea is still board flat, with the lift of an occasional long-period swell from somewhere way down south. We worry about getting too close to the coasts of Colombia and Ecuador, getting tangled up at night with the big rigs of commercial fishing boats or threemen-in-a-rogue-panga. We are pencilling in waypoints where we might tack over to port, and wondering, how weatherly is our boat in light air and chop? Most Dolphin 460s carry a 150% genoa, perfect for light air upwind, but OCEAN is rigged with a non-overlapping jib – a sailplan for breezy Caribbean trade winds that leaves us underpowered in less than 10 knots of equatorial air.

DAY THREE. There’s nothing like the smell of diesel in the morning. We poured our six jerrycans into the main tank, so now our 450-litre fuel tank is full again. This is becoming a most unusual passage: never have we burned so much diesel with more than halfway still to go. The wind is continuing light, and now a tedious chop has sprung up. Still motorsailing under main only, still heading 190°T, away from the Galapagos, but getting south to the promised land of the southeast trades. Already worried about fuel, we go through the fuel consumption calculations of using one engine or two, at 1,800, 2,000, or 2,200rpm.

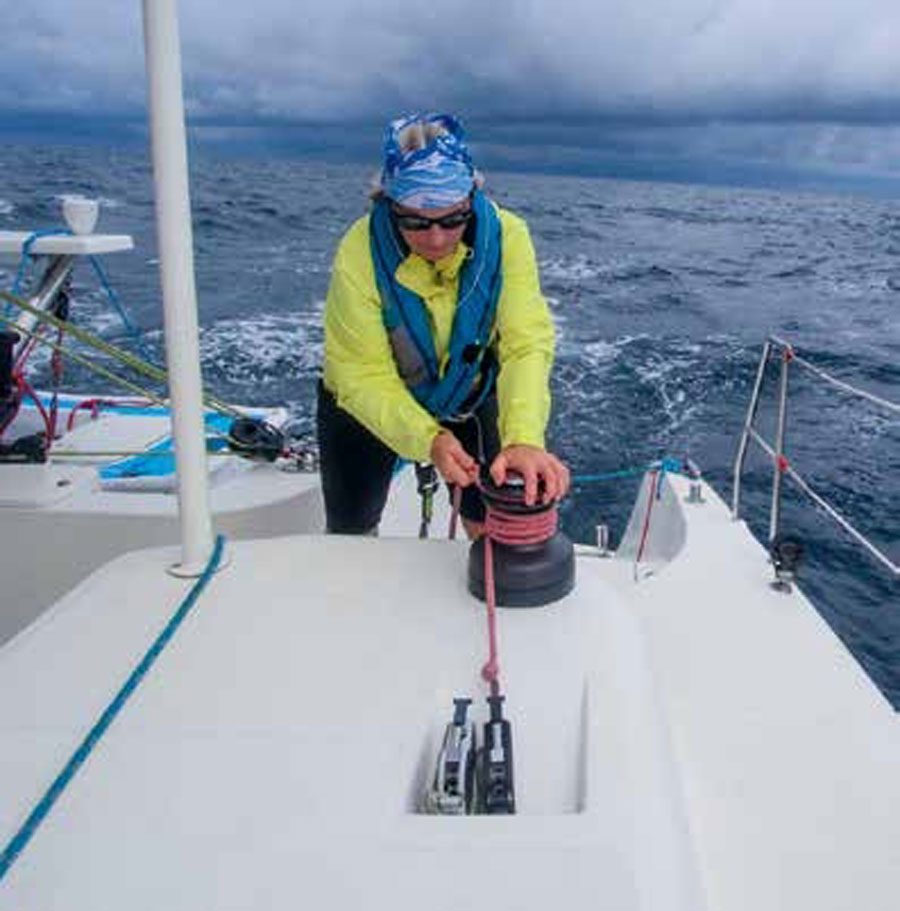

DAY FOUR. After much debate – and prompted by a sprightly new 10-knot SSW wind – we’ve tacked over to port. Now we’re heading directly at, or sometimes 10 to 20 degrees below, the Galapagos, 555 miles away. Everything seems okay. But late in the afternoon, a 20-mile line squall from the northeast slides over the top of our world, complete with a sheet of white-out rain and our own sticky doldrums. Drop the main into the lazy bag, zip the cover, and motor slowly through the rain. We’d hoped that we hadn’t tacked too soon. We’d hoped that we wouldn’t come to regret it. We’d hoped that we were safely to the south, out of the ITCZ. Well, the line squall answered that question. Squall clouds all around us now. At least we still have a 1.2-knot current boosting us toward San Cristobal.

DAY FIVE. Some sailing, interspersed with mostly motorsailing, as the wind flips from SSW to S to SSE and back again. The ITCZ does seem to be to leeward of us now – another line squall approached this afternoon from the northeast but was rebuffed by the advancing airmass of southeast trade winds. In the battle of the winds, OCEAN is no longer a ping-pong ball. By afternoon we are sailing close-hauled to the Galapagos in 14 knots of wind. Smooth seas, except when politely ruffled by a 1.7-knot favourable current. We’ve turned off the engine, finally. A morale booster!

DAY SIX. Getting close: only 270 miles to go. A posse of killer whales – killer whales! – passes by two boat-lengths away. Serious sea animals.

DAY SEVEN. At 0930, only 123 miles left. Harriet and I cross the Equator for the fourth time since we’ve been married and voyaging together; we toast Neptune and Poseidon for taking care of us. We run two loads of laundry, fire up the watermaker, and 40 miles from the Galapagos, heave-to and go over the side to pop off a few stray barnacles. Like New Zealand, the Galapagos is on guard against invasive marine species.

20/20 HINDSIGHT. As advertised, this ‘battle of the winds’ passage was fluky and frustrating. We burned a record amount – 420 litres – of diesel. Maybe we just should have accepted going slower and taking longer. And maybe we tacked too soon – it would probably have been better to carry our starboard tack farther south, into a (hopefully) better sailing breeze. But that’s the thing with ocean passages: even 20/20 hindsight is never perfect. BNZ