Cruising the tropical South Pacific holds huge appeal for many Kiwi boaters, but safely navigating around its myriad islands and negotiating narrow reef passages can be challenging…

Each year cruisers set out across the Pacific pursuing the dream of sparkling lagoons, white, sandy beaches and colourful coral. However, inexperienced crews can underestimate tricky lagoon passes, run into coral heads or end up anchored on a lee shore after wind shifts. For some, the dream of the South Seas ends in a nightmare of boatyard repairs or even wrecked on a reef.

So, should we give those turquoise atolls a wide berth? Absolutely not – it just takes some preparation, caution, and a good dose of common sense to minimise the risk and live the dream.

LAGOON PASSES

Tide tables can often be unreliable, and the times of slack water are influenced by many factors. During and after a period of strong winds and/or high swell, the water level inside lagoons is generally higher and the outgoing current stronger, which may persist even during the rising tide. It is, therefore, wise to arrive in the morning to allow plenty of time to await favourable conditions.

Watch out for signs of current: churned up water and standing waves outside the pass show that the current is still running out, while the same phenomenon inside the lagoon indicates an ingoing current. Slack water is, of course, ideal, but entering against the current or with a moderate current is also possible as long as wind and current are going in the same direction.

It is unwise, often dangerous, to attempt a pass when wind and current are opposed! Even big boats can get into serious trouble if they get trapped in high, standing waves. The current runs strongest in the deeper sections of the pass; in wider passes, it is sometimes possible to sneak in along the fringes of the pass where the water is shallower and calmer.

NAVIGATION IN THE LAGOON

Once through the pass, the harsh ocean conditions are left outside, but you may not have necessarily reached a safe harbour yet. The fetch that builds up inside the lagoons of larger atolls is more than a cruising yacht can comfortably (or safely) ride out at anchor. So quite often it is necessary to cross the lagoon to find a safe anchorage.

Many atolls are uncharted or only partially charted at best. Sometimes charts give the illusion of detailed information which then turns out to be offset, incomplete, or utterly wrong. We rely on eyeball navigation with a lookout on the bow.

It is best to explore unknown areas on clear days with the sun high in the sky so that coral heads (bommies) can be seen from afar in the dark blue of the lagoon. Polarised sunglasses filter reflections and improve the visibility. When the sun is low in the sky, it is impossible to distinguish reefs beneath the glittering surface of the sea.

On days with white clouds like cumulus, or a high-altitude haze, visibility is also impaired. When rain clouds darken the sky, reefs can be clearly seen, but as soon as rain starts pouring down, visibility above and below the surface reduces to zero. In murky water – when the lagoon is churned up due to strong winds or a high swell breaking over the reef – it is also difficult to spot the bommies.

We therefore take advantage of sunny days to explore the lagoon and find anchorages for different wind directions, marking dangerous coral heads near the route on the chartplotter. In case of a sudden wind shift, we can safely cross over to the protected side of the atoll even during squalls.

When planning routes, we work extensively with satellite images to get the big picture of the location, but also to find promising anchorages.

ANCHORING IN THE LAGOON

Once you have reached the protected side of the lagoon the quest for a large, sandy spot to drop the hook begins. It helps to scrutinise high-resolution satellite images beforehand, to know where to expect possible anchorages.

On Pitufa we strictly avoid damaging coral, so the search for an anchoring spot can take a while. Bommies are less numerous on the shallow reef shelf (1-5 m), you can see the bottom clearly, and not much chain is necessary to have an adequate scope. Additionally, you have the benefit of floating in minty swimming-pool colours.

Slowly manoeuvring in uncharted, shallow water is rather exciting at the beginning, but you quickly learn to distinguish the different shades of turquoise over sand and green to brown over coral and to read them as depths.

Don’t forget to check the tide table before deciding on an anchoring spot.

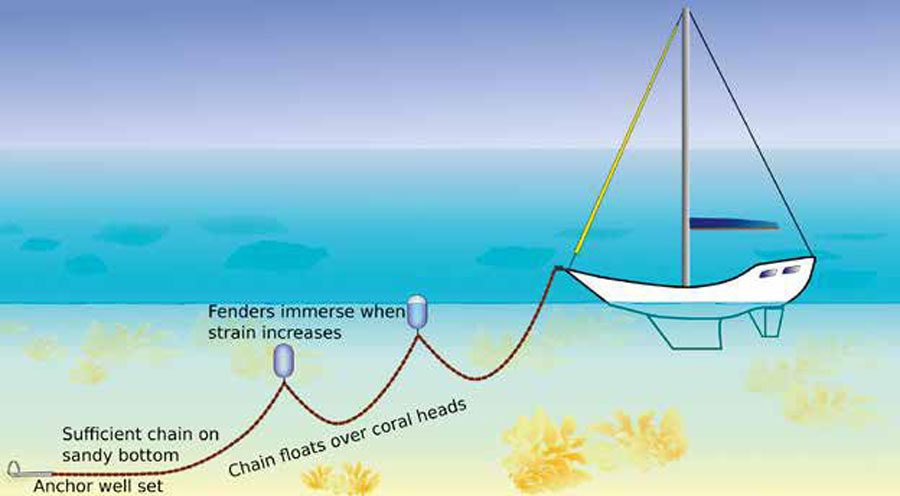

If the sandy patch is not big enough to swing around with sufficient scope, we float the chain using fenders or buoys. Sadly, we often watch neighbours fouling their chain in coral, either due to a lack of awareness, experience, or adequate anchoring gear. Questioned about their motives, the reply is usually an indifferent shrug, or paltry excuses. Recently old salts shocked us by stating their usual method of anchoring was to drag the anchor until it gets stuck in coral. The results of such behaviour are desolate rubble fields underneath popular anchorages and anchoring bans which then keep out ecofriendly cruisers as well.

A fouled chain is not only an environmental issue but may also endanger the safety of the boat. When the wind shifts and the chain is wrapped around bommies, boats are suddenly pitching violently on a short scope – an emergency that can end with a bent bow roller or even a ripped-out windlass!

Of course, it is true that floats partly nullify the weight advantage of a chain. It is therefore important to have a reliable, heavy anchor (properly set) and as much scope as possible before the first float. When the boat is floating around in a complete calm, the buoys can get stuck between bow and chain. Also, in locations with strong currents like narrow lagoon channels, a floated chain can lead to problems. Especially in combination with gusts, the buoys can float next to the hull (or even worse, one on the left and one on the right) causing the chain to scrape the keel. In such conditions a Bahamian moor is a safer, if somewhat more complicated and laborious, alternative.

KEEP ON MOVING

No matter how pretty the anchorage, it is always a good idea to get daily weather forecasts and move with the wind. When will the current anchorage become uncomfortable? Where can protection be found after the wind shift? When is it clever to start moving?

If you wait until the wind has shifted, you will have to motor against the wind or tack all the way. If you trust in the weather forecast and make a move in anticipation of the change, you will have a nice sail across the lagoon, but there will still be waves once you reach the other side – and the forecast wind shift might never happen!

In French Polynesia we often meet cruisers who are proud of ‘having done’ many of the Tuamotus in a short time. Those who rush through the atoll chain will be able to look back at thrilling (or nerve-wracking) passes, but they have not really experienced an atoll. Patient cruisers who explore all corners of a lagoon during wind shifts are rewarded with picture-perfect remote motus with bird colonies and pristine coral reefs. Only crews who spend a longer time at anchor off a village get the chance to make friends with the locals and enjoy an insight into the culture, daily life and challenges of communities on such remote and often quite barren islands.

The pace of life there is slow, so relax, take your time, and live the dream. BNZ

WHY ARE THE WAVES ALWAYS FROM THE SIDE?

Well, they are not always from the side, but quite often.

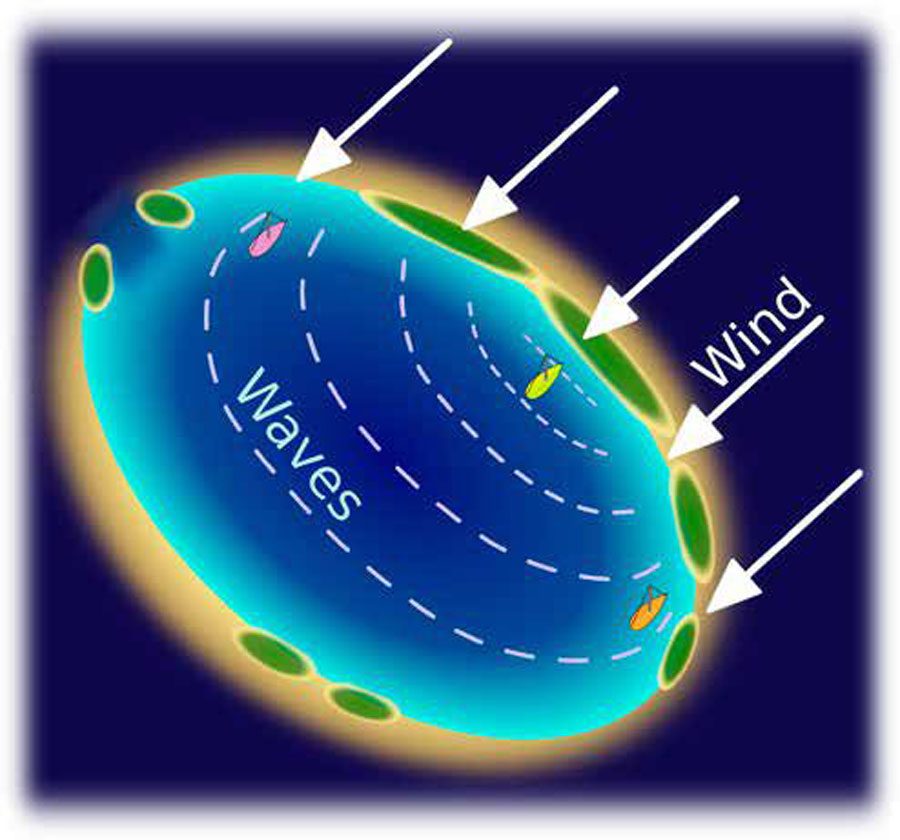

The reason for this phenomenon is wave refraction. Waves propagate more slowly in shallow water than in deep areas and so wave fronts are bent towards shallow zones (not to be confused with diffraction when waves are bent around obstacles).

The accompanying sketch illustrates this phenomenon in an atoll with wind from the northeast. The boats anchored in the north and east have waves on the beam as the shore is not rightangled to the wind direction. In strong winds these anchorages would become uncomfortable. The green boat in the northeast has the best anchorage with only small waves on the bow.

BAHAMIAN MOOR IN TIGHT SPOTS OR IN CURRENTS

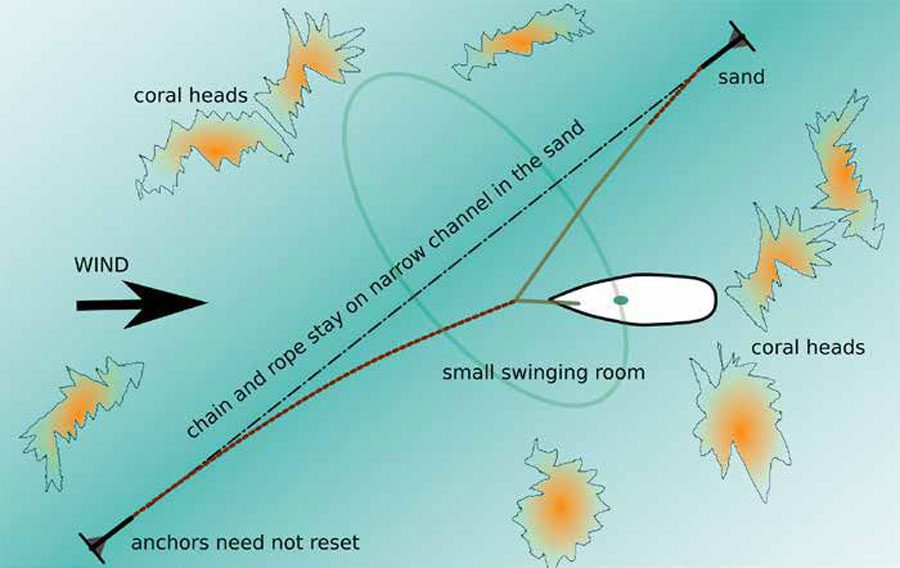

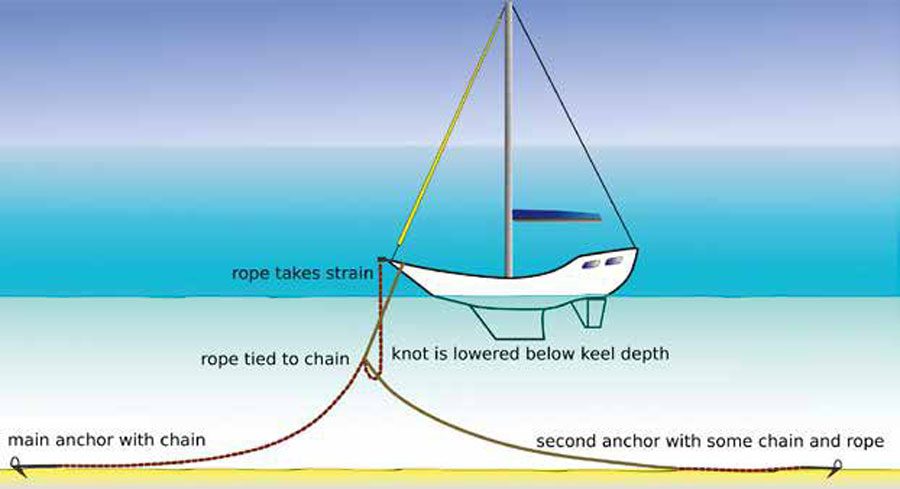

We drop the main anchor, pay out chain while reversing and drop the second anchor directly from the stern. Afterwards we lead the line of the stern anchor to the bow, knot the line to the chain under tension (best using a sacrificial line) and then lower the knot far enough so the keel can swing over the chain and line.

As the whole system is tensioned tightly, the chain and the line remain within a narrow channel (ideally over sand) and will not damage coral. The boat swings within a small radius and points the bow into the wind or current.

CORAL-FRIENDLY ANCHORING WITH A FLOATED CHAIN

On Pitufa we have two buoys (abandoned pearl farm floats) ready on deck with carabiners attached, to be hooked into our 10mm chain. As soon as the bow is centred over a sandy patch, we drop our ‘Bügelanker’ (similar to a Rocna) and pay out chain while gently reversing.

Look around at the surrounding bommies to estimate the swing radius. Well short of where the chain could possibly touch coral (even if the wind shifts) the first float is attached. Now there should be enough chain down to set the anchor pulling in reverse. If the scope is still not sufficient, a second fender can be added, followed by more chain.

In depths between 3m and 10m two fenders are sufficient to float the chain over bommies. Floating the chain in deep water is mere guess work, so not recommended. If you really have no alternative but to anchor deep, attach two floats together instead of just one – otherwise the weight of the chain will drag them down.

We often see neighbours anchoring in deep blue areas who then busily bring out a series of floats on 60m of chain. The first floats are pinned to the bottom by the weight of the chain, while the following floats bob on the surface – a pretty, but useless, arrangement of ‘alibi buoys,’ aka ‘feelgood buoys’.

THE CREW

Birgit Hackl and Christian Feldbauer set out from the Mediterranean in 2011 and sailed via the Atlantic and Caribbean to the South Pacific where they have spent the last eight years. More info and pics on www.pitufa.at