Readers of my vintage may remember – probably not fondly – being forced as school children to rote-learn passages from The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. It’s a lengthy, somewhat obscure poem, but literary merits aside, perhaps its greatest legacy is kick-starting the seabird conservation movement. Words by Lawrence Schäffler Photography by Matt Vance and Supplied.

At over 600 lines the work is the longest – and maybe the most famous – from the quill of 18th century poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. A man, it seems, who wasn’t averse to experimenting with opiates to enhance his view of the world.

Literary scholars have toiled over the poem and its meaning ever since it was published in 1798, but for us ordinary folk its only memorable lines are these:

“Water, water everywhere And not a drop to drink.”

I should point out that this couplet – capturing the irony of becalmed, parched sailors without freshwater yet surrounded by endless seawater – is a common corruption of Coleridge’s actual lines, which read:

“Water, water everywhere, Nor any drop to drink.”

But much more interesting than the sailors’ thirst is the poem’s treatment of an albatross which is shot with a crossbow by the narrator (the poem’s Ancient Mariner). This wanton act of killing incurs the wrath of the sea spirits and brings extreme hardship to the vessel and her crew. It rests heavily on the shooter’s shoulders for evermore.

It also results in the dead albatross being hung around his neck to remind him of his folly – and over the years his punishment gave rise to the idiom “having an albatross around your neck” – describing someone living with a heavy burden. Served the bugger right!

But over the following centuries, it’s often argued, the killing of the albatross also ignited a greater awareness in the public consciousness of the need to respect and conserve marine wildlife – long before the likes of Greenpeace entered the frame. More on this in a moment. First, some background.

RARE EDITION

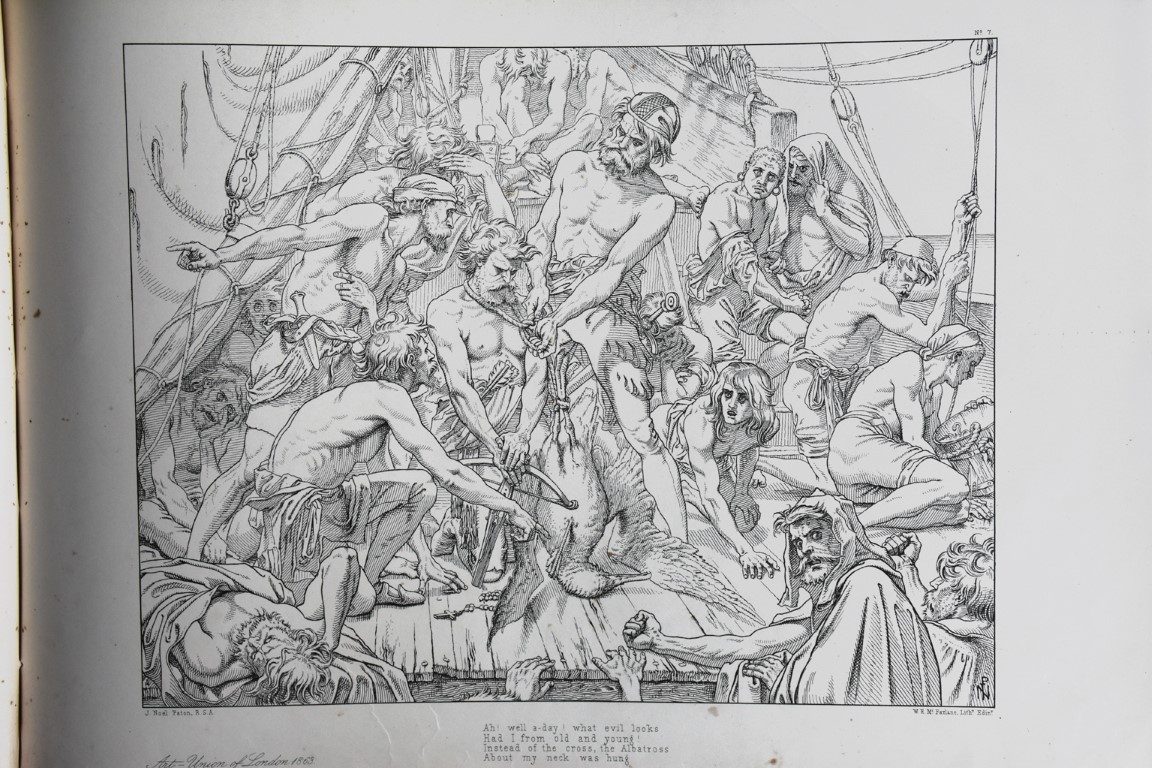

I was reminded of the poem’s legacy by a Boating New Zealand reader. Auckland’s Felix Tattersfield owns a very rare, illustrated edition of the poem, published in 1863. It was brought to New Zealand by his grandparents who emigrated from England in the 1890s. Felix inherited the book when his parents passed on.

Felix is a seasoned rum-racing sailor with a well-considered view of life and says the book – as well as his sailing background – are products of societies from different eras.

“My grandparents were relatively well-off and in those Edwardian times one of the obvious ways to display your wealth was having a sizeable and impressive collection of books. The Coleridge book was part of their library.

“In the same way, many people with a bit of money in New Zealand in the late 1800s/early 1900s began boating because that’s what wealthy people did – a boat was a clear illustration of your wealth. Me – and Coleridge’s book – stem from different but similar mindsets.”

His grandparents – and grandma in particular – were entrepreneurial sorts and soon established a thriving Auckland business (Tattersfield Ltd) dealing in mattresses, pillows and woolscouring. The couple had six boys and all were sailors.

THE ALBATROSS & CONSERVATION

By the closing years of the 19th century Coleridge’s poem was well and truly entrenched in the British school curriculum (and in schools in the colonies). Which is where most of us first encountered it – learning awkwardly-phrased stanzas off-by-heart.

But it also nurtured – even subconsciously – the growing conservation movement in the UK. The poem’s ‘popularity’ coincided neatly with emerging legislation and organisations designed to protect fauna and flora. Consider the introduction of the Wild Birds Protection Act in 1872 and the creation of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) in 1889.

Some 11 years later the RSPB’s membership had climbed to 25,000. Its main aim was encouraging better conservation and protection of birds and discouraging the wanton destruction of birds by wearing feathers and killing game birds for sport.

One of the most interesting studies of the Rime’s impact on the public’s imagination and albatross conservation initiatives is by Aussie Graham Barwell at the University of Wollongong’s School of Social Sciences, Media and Communication.

His paper – Coleridge’s albatross and the impulse to seabird conservation – was published in 2007 in the Australian publication – Kunapipi: Journal of Postcolonial Writing and Culture. The Journal no longer exists, but you can read the study at the following link: https://www.academia. edu/32931615/Coleridges_albatross_and_the_impulse_to_ seabird_conservation.

In it, Barwell writes: “…some of the gravitas coming from the poem’s canonical status can be harnessed to the international movement for albatross protection. This is no small achievement for a poem which began its public life by disappointing those buyers more than two hundred years ago who thought they were getting a naval songbook.”

Superstition

Sailors’ superstitions are as old as seafaring – but why is killing an albatross associated with bad luck? It seems the voyaging pioneers regarded the albatross as a supernatural bird because it could fly long distances without flapping its wings. They also thought the bird carried the souls of lost sailors – killing one would annoy the dead and bring bad luck to the crew and ship.

The Rime‘s storyline

The poem’s narrator is an old sailor (the Ancient Mariner) who accosts a man travelling to a wedding and tells him about his voyage many years ago.

A storm drove the ship into Antarctic seas where it became stuck in the ice. Fortunately, an albatross appeared and led the ship to freedom. But while the bird was being fed and thanked by the crew, the mariner shot it with his crossbow.

The sailors were outraged and blamed the killing for arousing the rage of sea spirits who blew the ship north to the equator where it was becalmed, without freshwater:

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

Water, water, everywhere,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, everywhere,

Nor any drop to drink.

The very deep did rot: Oh Christ!

That ever this should be!

Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs

Upon the slimy sea.

As punishment, the angry sailors force the mariner to wear the dead albatross around his neck, a burden to remind him of his ill-considered deed. Perversely, except for the mariner, the entire crew perished. The sailor then began to appreciate the creatures in the water. Where he’d previously cursed them as “slimy things”, he now understood their true beauty and he blessed them.

As he prayed, the albatross fell from his neck. But as penance he is forced to wander the earth, retelling his story to everyone he meets – teaching them to respect wildlife. An early David Attenborough.

The modern Rime

The poem received lukewarm reviews when it was first published – the publisher later told Coleridge most of the book’s buyers were sailors who thought it was a volume of singalong tunes. But despite its cumbersome language the poem’s made some surprising appearances in popular culture.

I’m not a heavy metal fan and can’t pretend to know the music, but the English band Iron Maiden used the poem for a track of the same name, on its Powerslave album (1984). At 13 minutes and 45 seconds long, it remained the band’s longest song for over 30 years until eclipsed by its 18-minute Empire of the Clouds (from the 2015 album, The Book of Souls). Both sound like purgatory.

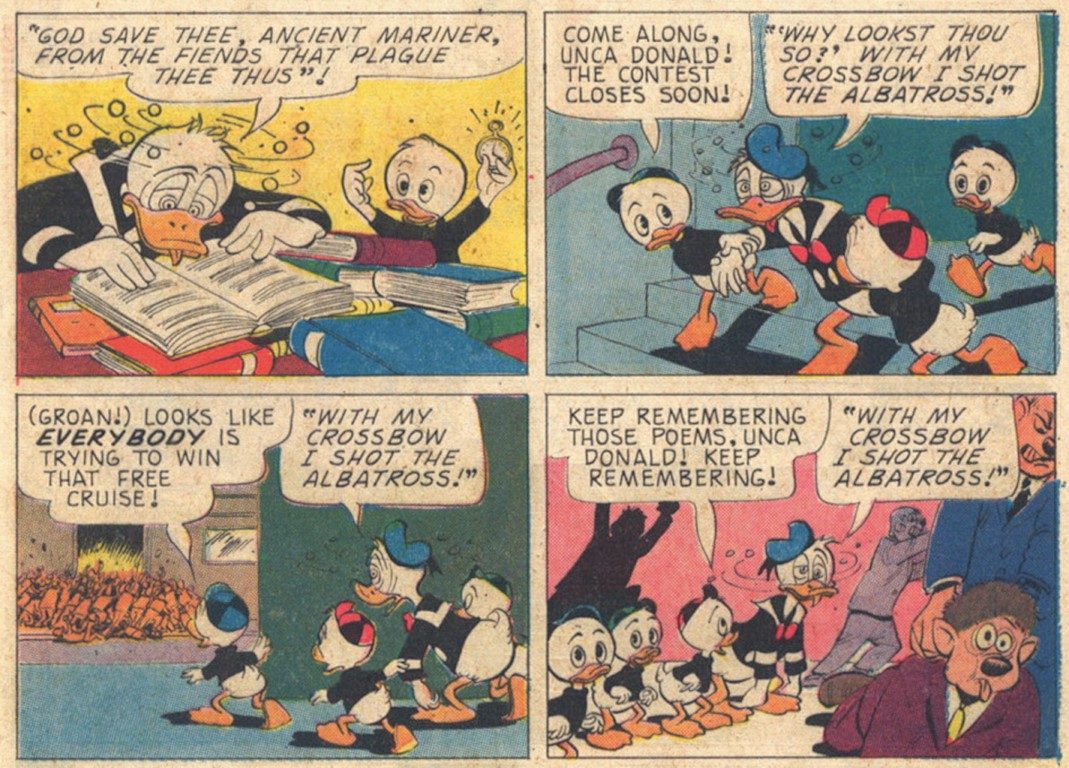

Much more accessible is Donald Duck’s attempt to memorise the poem in Carl Barks’ 1966 cartoon – The Not-So-Ancient Mariner – published in the Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories series.