There have been many solo ocean passages and circumnavigations, but few as challenging in concept and timing as that of Argentinian Vito Dumas in his ketch Lehg II.

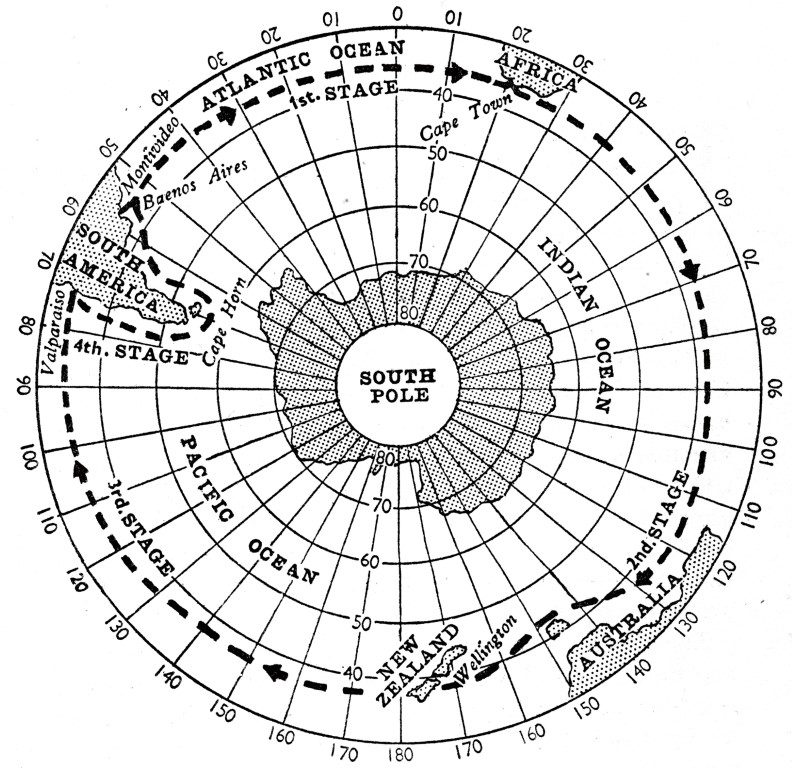

For it was 1942 – most of the world was at war. Although Argentina was neutral, a strange craft on the high seas was unlikely to receive any courtesies from any of the belligerents. To keep as far as possible from the conflict, Dumas decided to sail from Buenos Aires eastabout around the southern hemisphere’s 40th ‘Roaring Forties’.

Flying the unfamiliar flag of Argentina and completely unheralded, Dumas arrived in Wellington Harbour on Lehg II on 27th December 1942, 104 days and 7,400 miles out of Cape Town. Because it was wartime, no news of his passage had filtered through to the general public.

In Stalingrad the Red Army was breaking out of the German entrapment, the Americans were at the point of driving the Japanese out of Guadalcanal with help from New Zealand forces, the British Eighth Army (the New Zealand Division playing a central role with it) had defeated Rommel’s Afrika Korps and the Italians at El Alamein and had them on the run in Libya.

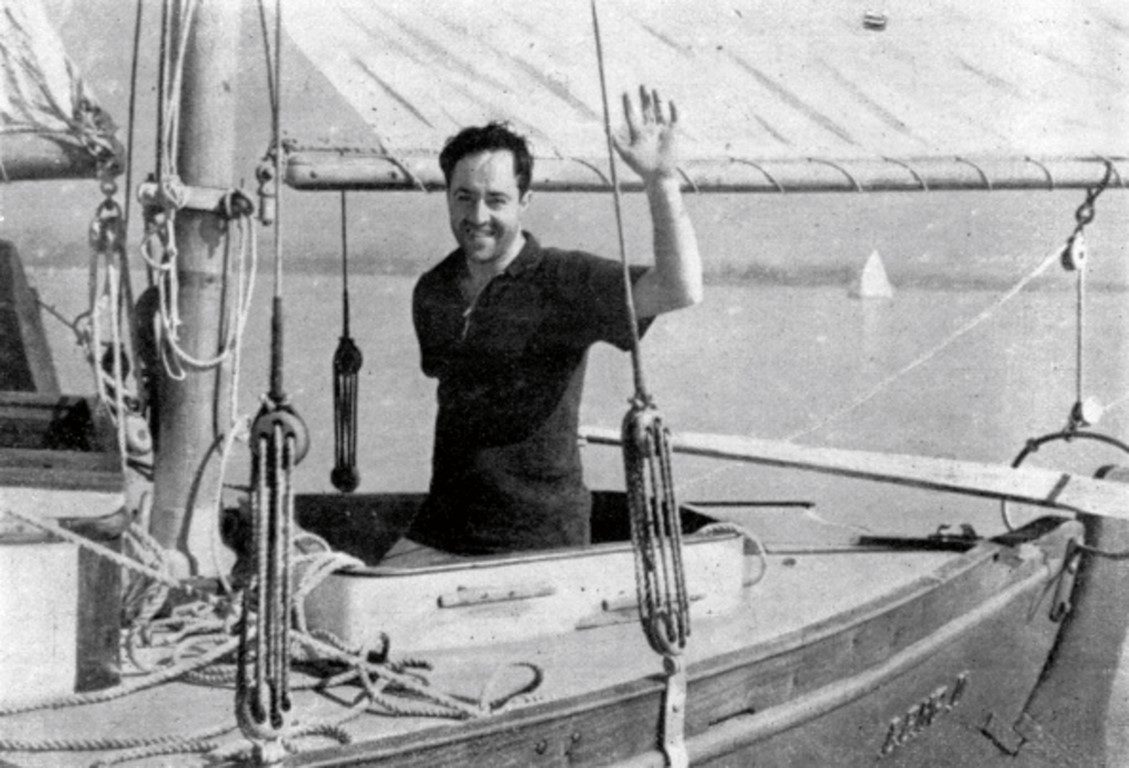

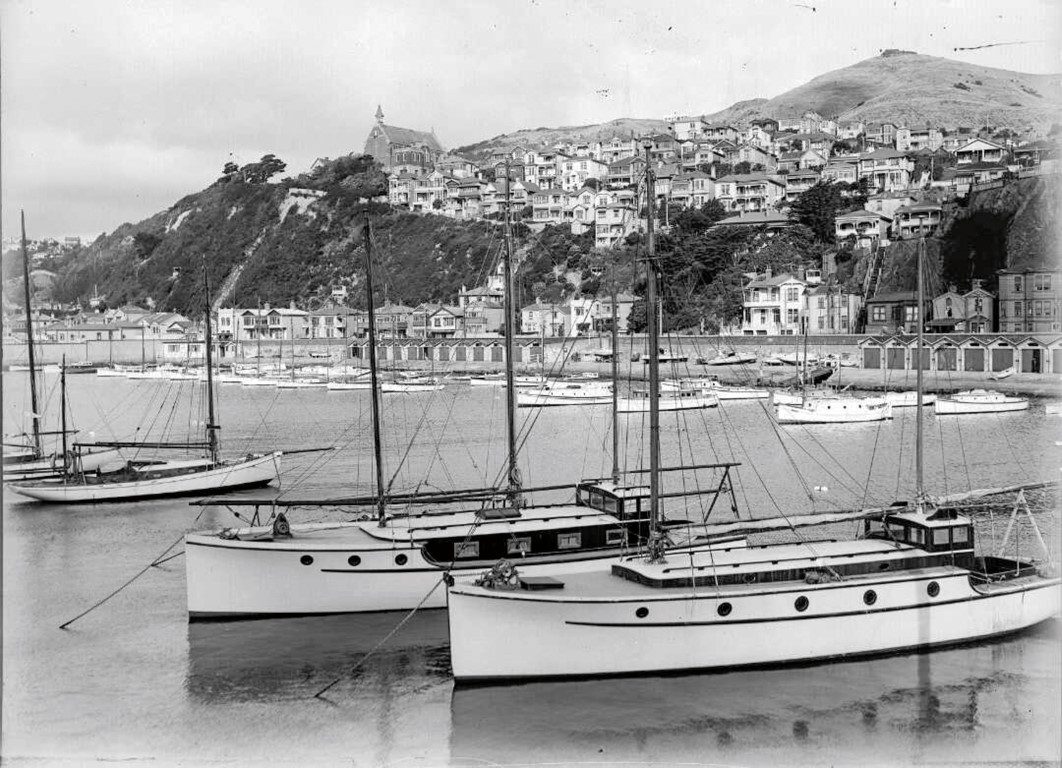

Soon after his arrival in Wellington, Dumas wangled Lehg II into the Boat Harbour after an initially lumpy berth at the main wharves, where he had attracted a great deal of attention. While fluent in Spanish and French, Dumas knew little English so found communicating difficult.

There was no Argentinian consul in New Zealand, but Spanish and French speakers soon came forward to make themselves known. Wellingtonians offered him warm hospitality. The Royal Port Nicholson Yacht Club, too, treated him as a remarkable sailor and gave him a splendid reception.

Of French-Italian ancestry, Dumas portrayed himself in conversation as a wealthy rancher, polo player, racehorse owner, pilot and champion swimmer. But this persona was not completely accurate – he was given to polishing the facts.

Indeed, New Zealanders had become accustomed to searovers, like George Dibbern with his Te Rapunga, who had made an art of living off the bounty of landsmen for some years. Out of cash, Vito Dumas had to borrow a £10 English note from a friend before he left South America. But he was personable and entertaining and respected for his seamanship.

After a refit at the Boat Harbour, carried out largely by US Navy personnel in exchange for a couple of bottles of whisky, Lehg II left Wellington on 30th January 1943, towed out to clear water by Arthur Holmes’ launch Vagabond, then wearing naval colours as a NAPS (Naval Auxiliary Patrol Service) vessel. Dumas laid a course directly across the Pacific for Valparaiso, Chile.

He had considerable experience as an offshore sailor. In 1931 he sailed Lehg, a 20-year old 8m racer highly unsuitable for the trip, from Arcachon on France’s Bay of Biscay coast to Buenos Aires – 6,270 miles in 76 days.

Although suffering hardships on the way, Dumas learned a great deal about sailing, and himself. He developed an obsession with solo offshore sailing. He gained superb navigation skills and endurance of mind and body that made the 1942-3 solo circumnavigation feasible.

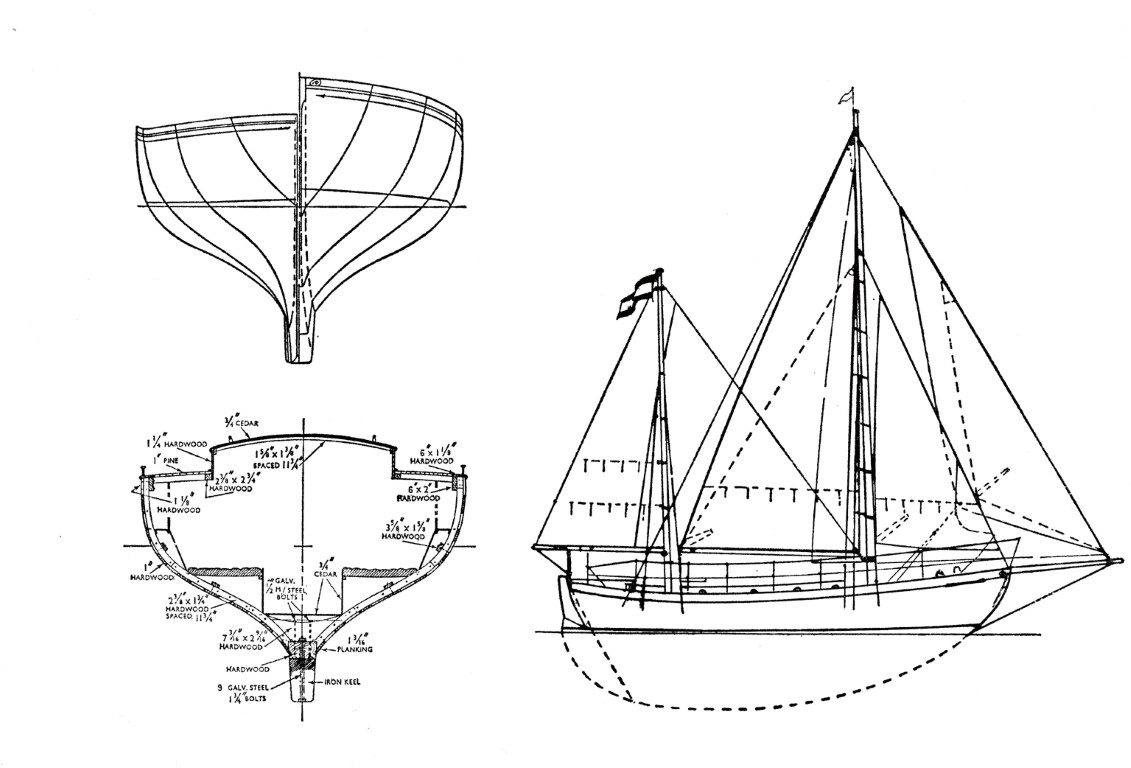

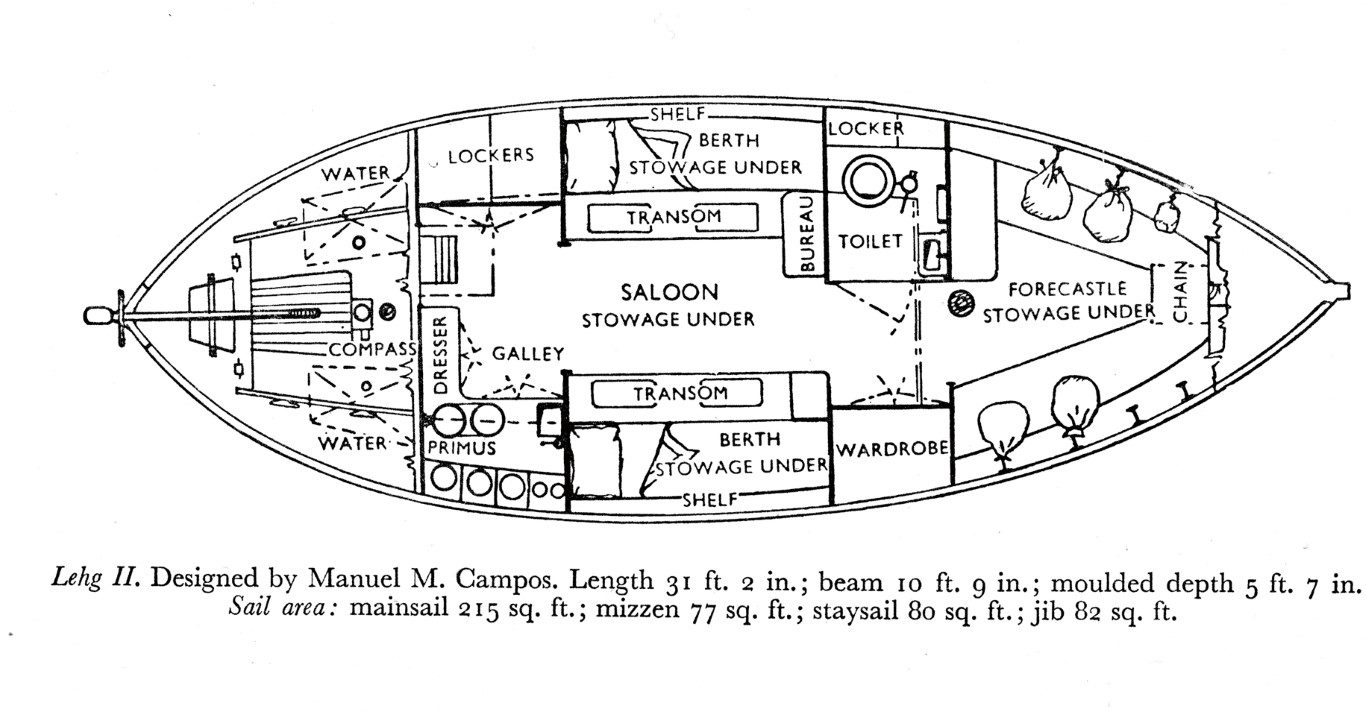

Argentinian yacht designer Manuel M. Campos had designed Lehg II in 1933 for Dumas, a double-ender in the Colin Archer tradition of Norwegian redningskoit pilot boats. Lehg II differed somewhat in that all ballast was external, and she was more lightly built and shallower than most Archers.

Built in Argentina in 1934, her overall length was 9.5m, beam 3.3m, draught fully-laden 1.7m and with an external cast iron keel of 3,500kg. She was planked with viraro, a local timber that looks like mahogany but is considerably stronger.

Originally rigged as a gaff ketch, Dumas set her up as Bermudan for the voyage. He kept her cabin-top covered with strong canvas to minimise leaks. Her rigging was heavy and her sails heavily-reinforced. He carried no radio as he feared being sunk as a spy.

He left Buenos Aires on 27th June 1942 on the short first leg of his voyage, a mere 110 miles across the vast estuary of the Rio de la Plata to Montevideo, the main port of Uruguay. This stretch of water had become greatly significant to New Zealanders because, only 2½ years before, HMNZS Achilles had taken part in the Battle of the River Plate, the first naval action of WWll.

This resulted in the scuttling of the German battleship Graf Spee on 17th December off Montevideo. Here, Dumas took his farewells from his many local friends and headed east, alone, across the South Atlantic for Cape Town, on 1st July 1942.

Conditions were bad. A violent southwest pampero had blown for days and seas were high. Lehg II had 4,000 sea miles to go. Very soon a serious leak developed from a shake in a plank forward. In 50 knots of wind, with canvas, red lead and putty Dumas succeeded in slowing the leak but knocked himself about badly in the process.

By 5th July he had a septic, open wound in his right arm. Struggling to manage the rig and keep on course, he contemplated amputating his arm. Then, overnight, the infection burst and he had blessed relief.

Because of his weakness, instead of expending effort in taking in sail for stronger winds, Dumas decided to leave all sails set at all times and let the boat look after itself with a set tiller, surfing down the troughs. This pattern proved so successful that he used it for the rest of the voyage. Only in the heaviest conditions would he stay at the helm and drive the yacht up and down the ocean rollers hour after hour at speeds which made for fast passages.

Lehg II reached Cape Town, 55 days and 4200 miles out from Montevideo, on 25th August 1942. Apart from a brief meeting with a British submarine, the trip was uneventful in terms of exposure to warfare.

Cape Town gave him a great reception. Dumas stayed for 20 days, rested up and re-provisioned, and departed for Wellington on 14th September 1942. He rightly anticipated that this passage across the Indian Ocean would be the most challenging because of the well-established pattern of frequent gales and high winds. Since he had perfected the mechanisms of sailing the yacht on the Atlantic crossing, he had better control of the vessel in the far more difficult conditions of the Indian Ocean.

Despite constant gales and freezing conditions, he experienced some calms as he approached the south coast of Australia and was once visited closely by three huge waterspouts. Passing south of Tasmania he made landfall in New Zealand at Cape Providence in Westland, then clawed his way up the west coast to arrive in Wellington.

The passage from Wellington across to Valparaiso was in enormous contrast to Dumas’ past passages, with many becalmed days. The ocean was truly Pacific. He reached Valparaiso on 14th April 1943 where he stayed in the comfort of this Spanish-speaking country, well looked after by the Chilean Navy.

He’d put considerable thought and planning into the timing of the voyage around Cape Horn. He decided that the optimum date to go around the Horn east-wise was midwinter, sometime between the beginning of June and the middle of July, when winds were on average less violent.

He left Valparaiso on 30th May 1943 and, after a relatively easy passage (if a passage around the Horn can ever be called ‘easy’) Lehg II arrived in Mar del Plata, Argentina, after only 37 days at sea and with Dumas at the helm for only seven.

After a brief trip to Montevideo for a week to thank his Uruguayan friends for their support, Dumas entered his home port at Buenos Aires, with ships’ sirens and whistles shrieking, to finish his voyage on 7th September 1943 – a total voyage of 20,420 miles and 272 days.

Dumas inspired many later ocean yachtsmen to follow his example, leaving sail on in heavy weather. In 1946 he made a third solo voyage in Lehg II to New York and back, and a fourth to Bermuda and New York in Sirio in 1955.

After his return, he gained the Spanish term for ‘The Wave Tamer’. He was a hero in Argentina – the Government gave him a pension and issued a postage stamp in his honour. In 1956 the Joshua Slocum Society gave its first Slocum Award to him in recognition of his extraordinary single-handed passages.