Thanks to the vision of John Gregg, the famous seiner chartered by John Steinbeck in 1940 is coming back to life. Fitted with hybrid propulsion, she will become an educational platform. Story by Bruno Cianci. Photos by Port Townsend Shipwrights Co-Op.

On March 11, 1940, while the Second World War was already raging in Europe, a seiner named Western Flyer set sail from Monterey, California – for a very different purpose than for which she had been built.

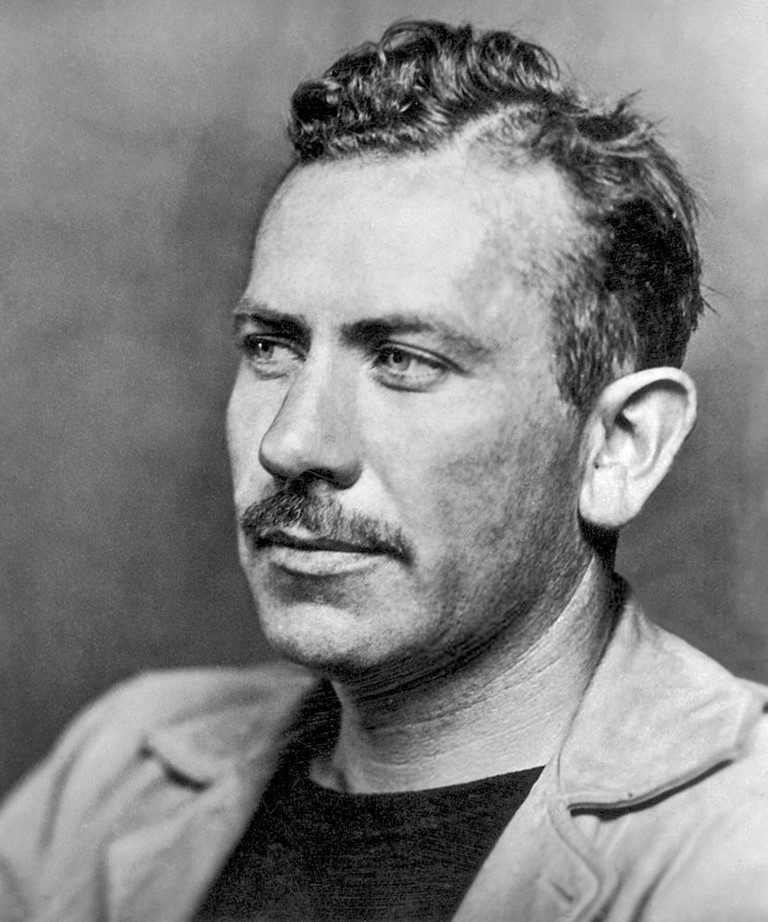

For six weeks a crew would be tasked with collecting biological samples of intertidal marine species. The expedition had been organised by two celebrities who had followed diverse paths, but who shared an unbridled passion for the ocean – an elective affinity that prompted them to charter the Western Flyer. One was Ed Ricketts, marine biologist, ecologist and philosopher; the other was John Steinbeck, novelist, who at the time of the journey had already penned Tortilla Flat and Of Mice and Men.

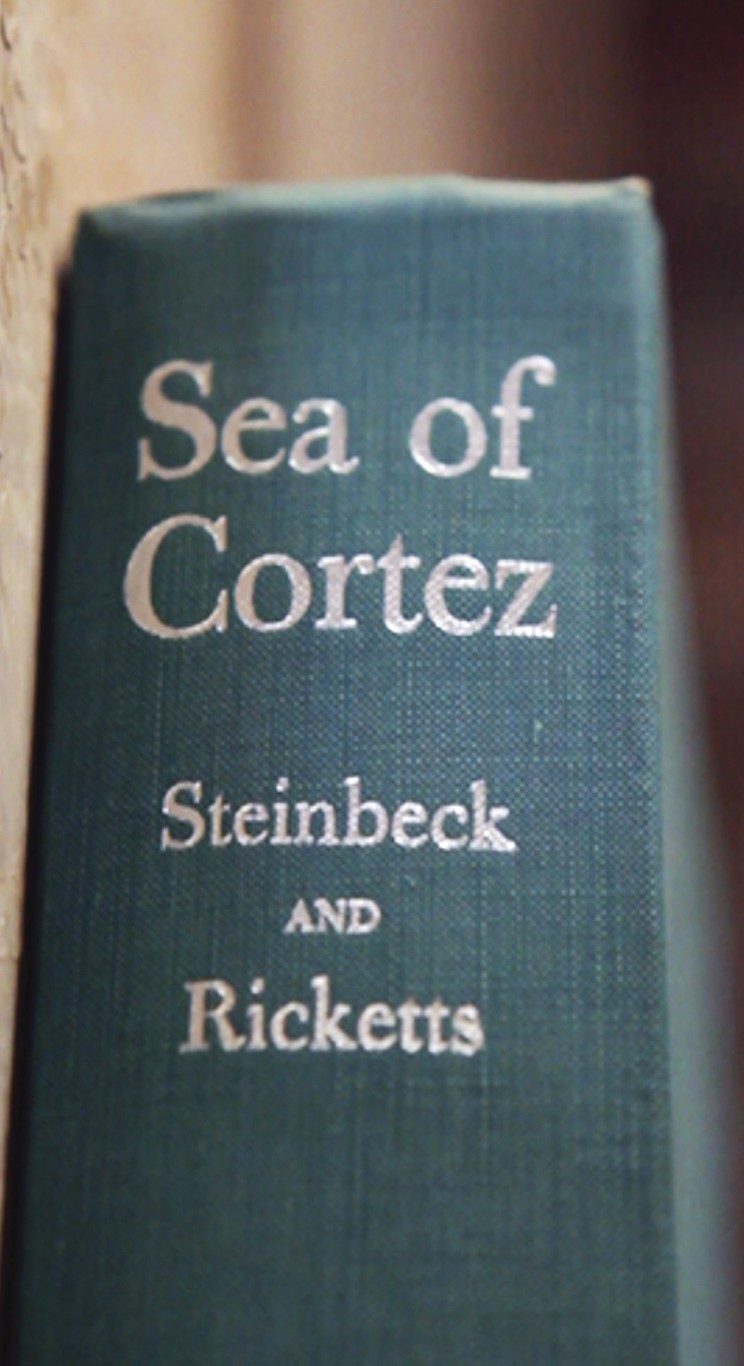

The Western Flyer was to be the floating home of Ricketts, Steinbeck and other crew members for a voyage through Mexican waters described in two books: Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research (1941) and The Log from the Sea of Cortez (1951).

Built in Tacoma, Washington by the craftsmen of the Western Boatbuilding Company shipyard as a purse-seiner for sardines, Western Flyer was launched in July 1937 as hull number #122. She was therefore built at the end of the sail era, and her hull lines retained the sleekness and efficiency necessary for wind-powered vessels. The construction, 76 feet (23.16m) long, was very solid.

She was originally built in Douglas fir; the frames were white oak; her interior furniture and trim was mahogany, and her guards and caps were ironbark. Everything else was fir: house, deck, planks, timbered stern, bulwarks, stem and backbone. At that time the shipyard was owned by Martin Petrich,

a craftsman originally from the Croatian island of Hvar.

When, after the second world war, fishing for sardines lost importance, the boat changed ownership. In 1952 she was purchased by Dan Luketa, and converted into a trawler for fishing Pacific Ocean perch, Petrale sole, black cod and Pacific cod in the waters between Oregon and British Columbia. When crab fishing became profitable in the 1960s, the boat began to be used around the Aleutian Islands for that purpose. In 1970, after Luketa had bought a larger craft to grow his business, a period of uncertainty began for the boat with many ownership changes. In the meantime – the year isn’t clear – she was rechristened Gemini.

In 1986 the boat was bought at auction by Ole Knudson, who used her as a tender to transport ocean salmon to the canning factories. Sometime later, while in a serious state of disrepair, the boat was purchased by a real estate developer to be used as a café in a hotel. Nothing more came of this project, which would have greatly debased the boat’s reputation.

The vessel, moored near Anacortes and with her hull in terrible condition, at one point began to take on water and sank twice, which caused her general condition to deteriorate dramatically. Fortunately, the boat was one day reported to marine geologist and drilling expert John Gregg, and it didn’t take long for him to fall madly in love with the idea of owning a craft whose exploits were known to him from having read Steinbeck.

He dreamed of returning her to the role she enjoyed in the spring of 1940: a floating laboratory where arts and sciences, as personified by Steinbeck and Ricketts, went hand in hand.

Gregg bought Gemini for one million US dollars; an outrageous price considering that the boat, in much better condition, had only cost $30,000 in 1976. Gregg wanted that boat!

“In 1969, at age 10,” he says, “I grabbed a book from a bookmobile by mistake, and I was forever changed by it. It was a 1951 edition of The Log From the Sea of Cortez, and it has intrigued me ever since.”

Gemini was transferred to the sheds of the Port Townsend Shipwrights Co-Op for restoration. The Western Flyer Project, financed by a cooperative foundation of the same name that Gregg commissioned, then engaged an expert shipwright named Tim Lee, ably assisted by Pete Rust.

The work turned out to be complex, says Lee.

“The boat entered our facilities in 2015. We were responsible for the reconstruction of the hull, deck and house. There was a little bit of work done to stabilise the hull, but she mostly sat while the Western Flyer Foundation and its supporting community took shape. Then a bit of work was done in 2017, as a result of a grant the foundation received, and to show some progress on the restoration. That consisted of removing the work deck and installing new clamp, shelf and deck beams.

“In January 2019 Pete and I fully took over the project when John Gregg gave us free rein to rebuild the boat. Besides maintaining the historical integrity, the fact that the Foundation wanted to put the boat back in the water and be economically responsible became the driving principle behind the rebuild. The bulk of the work was done in 2019. We started by removing the house and were almost done planking when Covid hit. We completed the hull, deck and house in June 2022, after two years of work with a reduced crew.”

To give some figures, the hull is only 8-10% original, whereas 80% to 90% of the wheelhouse could be saved.

“In theory we may have been able to save some of the old planking,” said Lee, “but it would have been massively uneconomical.”

Clearly, the pandemic dramatically slowed work progress. “Covid shut us down for five weeks,” says Lee, “then due to economic uncertainties we went from a crew of 8-12 to a consistent crew of just four for the next two years. It essentially added a year to the project.”

In terms of materials, Tim Lee is the best person to list those used for the rebuild. Since the original materials had largely deteriorated, they often had to be replaced with new ones.

“During the rebuild we used oak frames, Sipo for the planking, yellow cedar bulwarks, purple heart on the timbered stern, stem, and guards, and Douglas fir for the deck beams and deck overlay. The Western Flyer has a plywood sub-deck with a fibreglass overlay. Red cedar parts were used for the house front and the flybridge.”

It’s estimated that 40 people contributed physically to the work carried out at the Port Townsend Shipwrights Co-Op, for a total of about 36,000 man-hours, about a third of which were spent dealing with the old hull in the first year.

“I had the biggest crews,” says Lee, “when framing and planking: 10 to 12 people, but during the last month of the project, at the end of the spring of 2022, we had about 20 people working on the boat.”

In July 2022 the Western Flyer Foundation (WFF) arranged to tow the craft to Seattle for finishing, which is still underway. State-of-the-art equipment is being installed, including a battery-powered electric motor that will allow the Western Flyer to approach wildlife with minimal disturbance; a pair of Seakeeper gyroscopes will provide a clean, stable environment for people prone to seasickness. And lastly, an ROV (Remotely Operated Vessel) will allow the deployment of data loggers, and the collection of marine specimens and derelict fishing gear.

The WFF intends to have the boat in California this (northern) spring. When commissioned, the boat will be an educational and research platform based in Monterey and operated in the areas covered by Ed Ricketts, from Sitka (Alaska) to the Sea of Cortez. The WFF will be offering free, experiential learning programmes to students of all ages on land and aboard the Western Flyer, with a primary focus on those from traditionally underserved communities. Teachers and students will experience and study marine and coastal ecosystems and be able to immerse themselves in the rich literary and historical traditions associated with the vessel.

“We anticipate the Western Flyer will spend 26 weeks each year in its home port of Monterey. The rest of the year the craft will venture north, as far as Sitka, and on alternating years, south, to the Sea of Cortez. Along the way we intend to call on small ports that are seldom visited by research or educational vessels,” says Gregg. “Annual symposia will be held in Monterey to ‘train the trainers,’ preparing them for our visits.”

This [northern] summer the Western Flyer is scheduled to visit Alaskan waters, whereas in 2024 it will be the turn of the Baja California – the location where Ricketts and Steinbeck’s journey transformed the trawler into a floating legend.

“The new explorers on board will be challenged, and not just by technical issues. Subjective impressions will be teased out of them through writing, painting, photography, and documentary production, thereby engaging both hemispheres of the mind,” says Gregg. “This is where I feel I’m out of my depth. But by working together with others – the Steinbeck/Ricketts model – we will be more complete, and the creativity of others will help create a holistic vision aboard the Western Flyer. The project will embrace both the seen and the senses.”

John Gregg can’t wait to see what he has done.