Blokes never age – at least in their minds. And so when I suggested a boat trip up a half-forgotten creek, my neighbour Steve was immediately up for it. We were Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn all over again, but with all the modern gizmos in hand. Story by Alex Stone.

Steve’s boat is a flash new McLay Sport Fisher 575, purringly powered by Yamaha. Before departing, he and I conferred with the aid of mobile apps, trying to get tide and weather right. Our goal was the Clevedon Wharf up the Wairoa River, just across the Tamaki Strait from Waiheke Island.

The ‘Port of Clevedon’ and its wharf have a fascinating history, and back in the day the river traffic bustled. From October 1864 to June 1865, the 13 ships of the Waikato Immigration Scheme arrived in Auckland, bringing with them almost 4,000 immigrants.

Two-thirds were from Britain and a third from the Cape of Good Hope. This was a result of the New Zealand Settlements Act being passed in December 1863, allowing the seizure of land from any Māori who had waged war or carried arms against the Crown.

The aim was to lay out towns and farms and place selected immigrants on the land. So, settlers were needed. The thinking was the immigrants would quickly populate the land south of Drury, creating a buffer zone between Auckland and the Waikato, and consolidate the colonial government’s position after the New Zealand Wars.

Actually, the intention was to bring in 20,000 immigrants. Free passage and a land grant for immigrants were widely advertised in newspapers in England, Ireland and Scotland, and also in the Cape Colony. Suitable applicants were defined as “agricultural and railway labourers, mechanics (craftsmen and artisans), miners, and general labourers.” All would receive a town lot and a ‘suburban’ section – five acres for the Cape migrants and, as added incentive to make the long voyage, ten acres for those from Britain.

They had to remain on and improve the land for three years before an official grant would be made to them. At the end of October 1864, the scheme was suspended but a number of settler families, including many from the ship Viola, still settled in the Clevedon district.

It was tough enough just getting there. The Viola, under a Captain Mitchell, sailed from Glasgow, Scotland on 8 December 1864 and arrived in Auckland on 4 April 1865. Of the 340 immigrants aboard, 11 children and adults died during the voyage and they were all buried at sea. There were eight births.

But positive PR spin was alive and well in those days. The long, arduous journey to Auckland was promoted as “comfortable, with a liberal diet, under the control of an experienced medical man. The New Zealand Government will pay for you and your family to sail to the New Zealand colony where fertile, favourable land lies vacant, waiting for your plough.” Not quite.

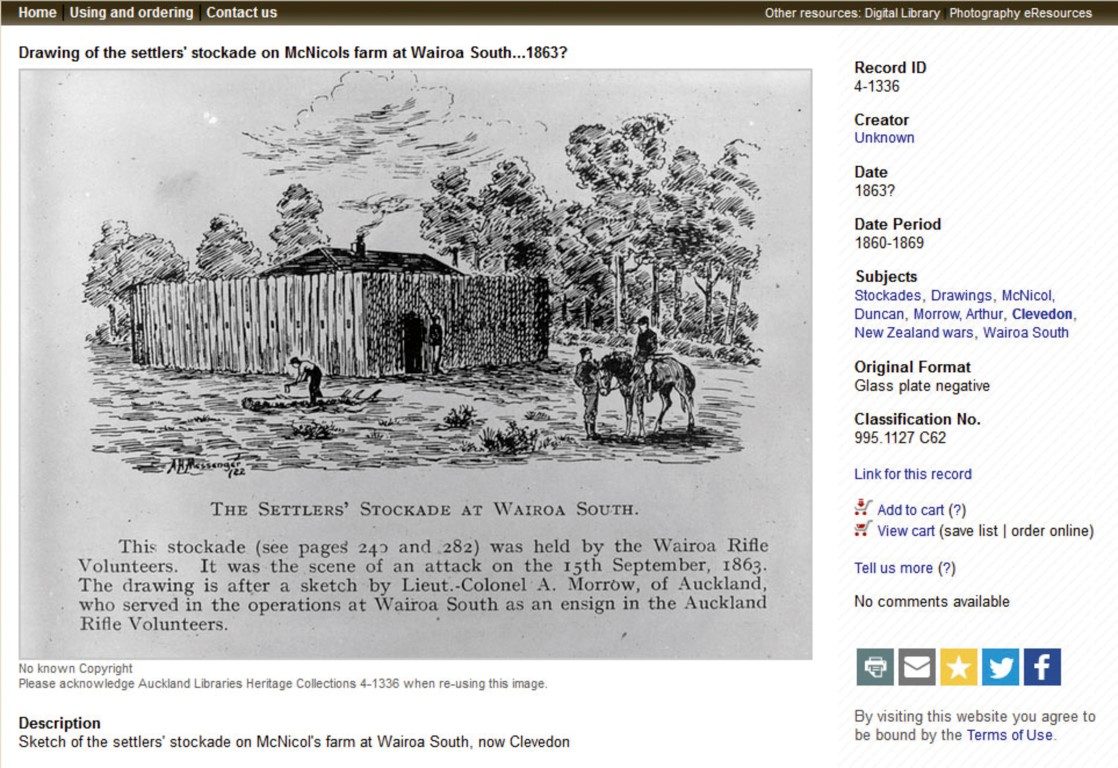

The New Zealand Wars were still raging in 1864, after the Invasion of the Waikato in July 1863. There was real concern, later proved true, that Māori from the Coromandel would cross the Firth of Thames to come to the support of their Waikato kinfolk. To that end, there were gunboats patrolling the Firth, ready to intercept any renegade waka.

But this wasn’t mentioned to the innocent settlers. “It is therefore ironic that for some, the voyage was fraught with death, disease, and little food,” writes contemporary historian Alison Drummond.

The reality is reflected more accurately in recollections of the passengers: “She [the Viola] took her departure from Glasgow on 8 December 1864 and was detained in the chops of the Channel for ten days … Crossed the equator 16 January and rounded the meridian of the Cape of Good Hope on 17 February. Rounded the north cape of New Zealand on 27 March and encountered heavy S.E. gales for three days” (extract from the Southern Cross newspaper, 5 April 1865).

“A pig fell through the skylight into the second cabin, ran into mine and made a terrible noise and a nasty smell,” remembered one passenger.

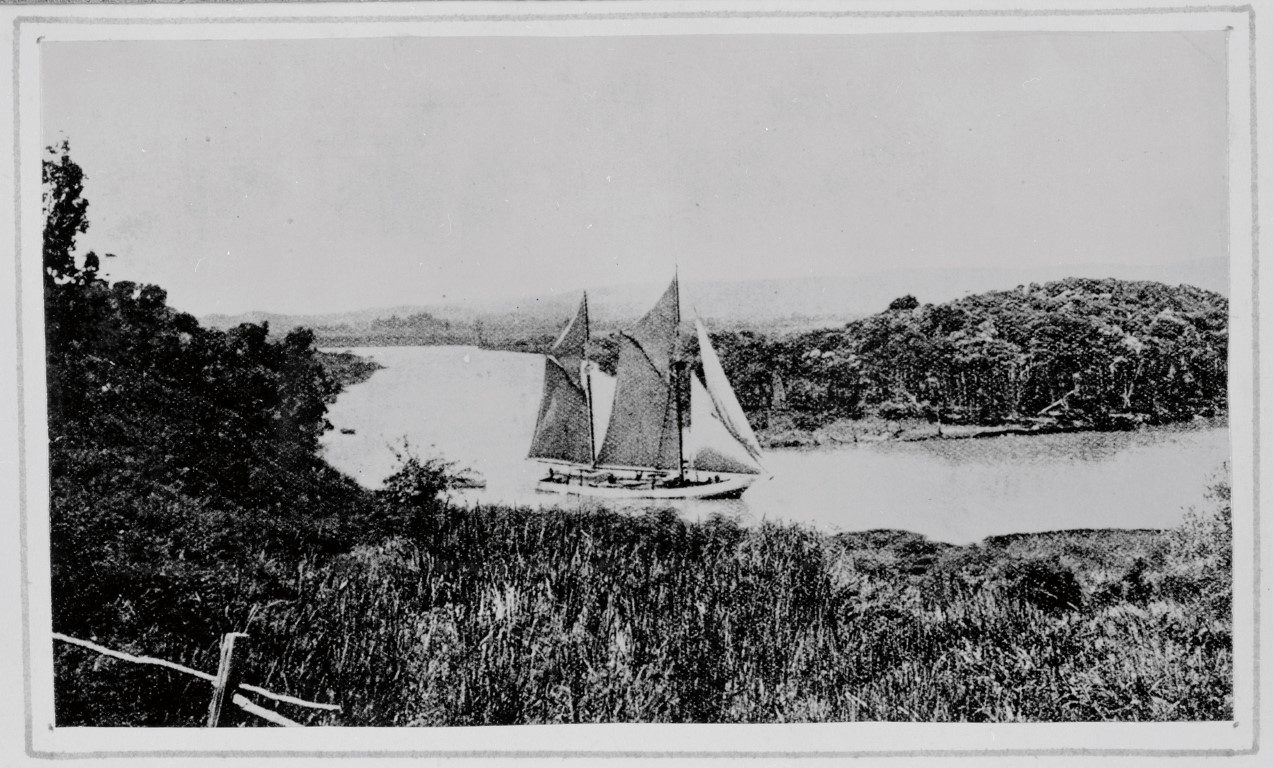

Once finally disembarked, the prospective settlers were transferred in small sailing cutters to the Wairoa River. And so began their first experience of their strange new environment as they navigated their way upstream. Things remained tough for a long while.

“On landing, the immigrants were given 15 days’ rations to enable them to live while building their homes. A Mr McLean built his home in the Otau settlement, of tea-tree sides with a nikau roof, and two days after he got his family in, another daughter was born, the first white child born in the Wairoa.

“The early settlers had many difficulties to contend with, the district was then a howling wilderness without roads or facilities of any kind” lamented an Auckland Star report on the 33rd anniversary of the Viola landing.

In August 1865, the Anglican Minister, Reverend Lush “found the poor people… very discontented”, and “wishing they had never left the Old Country.”

“Unemployment was a serious problem; without work there was no money, no food, clothing, or the ability to move somewhere else,” wrote a descendent, Dr Michelle Smith.

In those days Clevedon was fairly remote from Auckland. There was no road – the river was the main way to get there.

THE VOYAGE

Round Whakakaiwhara Point and Te Tauranga o Tanui Bay at Duders Regional Park, Steve and I found the river mouth at low tide, the channel marked by 11 poles in Wairoa Bay (keep them to port going in). Even at low tide we had about 1.5m of water under the boat.

The trip upriver offers a fascinating view. Along its banks lies the historical trajectory of waterside living in the Hauraki Gulf, laid out like a real-life diorama.

At the river mouth are some fish traps. On the mud banks, birds fossick for food as they’ve done forever; there are godwits, herons, paradise shellducks. We are taken by the oddball majesty of four royal spoonbills – all haughtiness and awkwardness, with wayward white head plumes like a punk rocker’s hairstyle.

These birds arrived from Australia in the late 1800s, uninvited but welcome anyway for their sheer funkiness. And just like royals today, they’re not keen on a selfie with me, so I missed the photo op.

Here is a remote farm, done up smart with brick and tile in the 1950s – in those heady days wool was a pound a pound. There are still some sheep around and a crumbling wharfside. In a paddock we spy a collection of rusty channel buoys, looking like the lost marbles of some excommunicated giant, and an accidental sculpture park also.

Round a bend we see a manure-whiffy barge, obviously still used for transporting livestock. In the past, the wharves of the Wairoa River were commonly used for the transfer of stock to and from many Hauraki Islands.

Here is a bloke patiently mending a net sitting on the rickety jetty, ciggie dangling from his mouth, his bare feet half in a leaky dinghy. Behind him, a trailer-sailer that has neither trailed nor sailed for some time.

Like many secluded waterways around the Gulf, there are many tucked-away moorings, with boats lying cheaply, patiently, not often visited. The moorings continue up the river for a surprisingly long way, with more masts appearing, first above the paddocks, then around the river bends.

The first collection of boats we come to is at the Brooklands Boating Club. Todd Wheeler (0274 752 832) is yer man to talk to about tying up at the work dock. The tide is streaming in at around 3-4 knots, so it presents some docking challenges. They have a bunch of new pole moorings there, going at reasonable rental rates, for those who might like to escape the world of shiny marinas.

Going upstream we are in our element: boat spotting, especially eccentric boat spotting, is our game. Here are mouldy pleasure palaces reflecting the faded playboy dreams of their once hopeful owners, their sleek lines fuzzed now by age, lichen and bilge water.

Here are some round-the-world yachts that maybe never took the voyage, tillers dreaming of a steady hand on them yet again – once the rigging is fixed and the bottom scrubbed. We see some people living cheap in waterside cabins while finishing that never-ending homemade boat project. Or perhaps just living simply, quietly and cleverly.

Coming into view are the dinghy racks and clubhouse of the Clevedon Cruising Club, some of its boats on the hard. There’s Waitomo diesel fuel available here, but only if you have a Waitomo card. You may need to do some sweet talking to get some.

Commodore Bruce Robson reminds me that the club is essentially a private outfit, originally established for friends and family of the local MacKenzie farming dynasty. Like so many other clubs, you need an introduction to become a member. In 2019, the club celebrated its 75th jubilee by (among other things) producing a fascinating historical booklet.

The club hosts the annual Waitemata Woodies rally for traditional launches, clears its docks for the visitors, and lays on a welcoming barbeque. The club’s also the official navigational custodian of the navigable Wairoa, and so maintains the marker posts and lights at the channel entrance.

One of those poles, we noticed, sports a bird house. Bruce said this has become an in-joke at the club – at his expense. Some gulls were soiling the light atop that pole, so Bruce decided that if the birds wanted to live there, he’d provide a motel for them.

The Riverhaven Sculpture Park is just behind the Clevedon Cruising Club, and well worth the visit if outdoor art rings your bells. Unfortunately there’s no access to the park from the river – save it for when you come again by road.

As the mangroves thin, things change. There are enormous mansions carrying the overt aesthetics I associate with Russian oligarchs. The lifestyle dream, complete with a personal dock and your own flash launch tied up there. There’s a subtle change from the mangrove ecosystem to raupo riverbanks, more greenery and some stands of kahikatea trees, although we are still in tidal salt water.

The land becomes more manicured, and very expensive-looking horses gaze haughtily at us. The road from Maraetai to Clevedon makes an appearance riverside. Cars rush by but our boat doesn’t, as the river becomes narrower. No matter – this is the moment to take your own sweet time.

Ironically, the biggest boat we see on the river – a 60-foot aluminium schooner named Blizzard – is the highest up. It’s at a spot where one of the ground rules of up-the-creeking becomes apparent: here the river splits around an island. The deeper channel is the one that does the wide curve around the island, not the one that appears to go straight. Rule of thumb, the outside of any curve in the river, is usually the deepest, safest route.

If you obtain permission to tie up here, it’s but a short walk southwards along North Road to Woodzone, a crafts-emporium selling the best of New Zealand timber wares.

There are four fluffy paradise shell-ducklings in the stream. Their parents’ distracting display is unconvincing. The ducklings, imagining they’re on their own, submerge vigorously. They pop downwards holding their breath and pop up, jiggle-jiggle to check where we are. We give them a wide berth.

There’s a bright bit of orange plastic in the water. No wait, it’s moving. It’s a giant koi carp. Steve and I tut-tut about this environmental vandal, but then figure it surely can’t know about – or help – its alien status.

We are thwarted just a few hundred metres from the Clevedon Wharf by a tree just under the water. A bit more tide, a half an hour wait would do it. But we must turn back – Steve has his daughter to pick up from school. No matter, a lovely trip anyway. I make a mental note to suggest to the Local Board to clear the upper reaches of the river of potential blockages.

THE CLEVEDON WHARF

For many years the early European settlers of the Wairoa district had used ‘The Wairoa Landing Place’ as a common meeting spot, access to a general store, post office and to their vital artery of river transport. On the western bank had stood the wharf and butter shed. A general goods shop (including a Post Office) was located behind the wharf and facing the road. The eastern side had a blacksmith shop and sawmill with other small buildings scattered about.

It was a bustling little community until the present Clevedon village was established nearby. There’s a pub and a restaurant now just by the wharf, but not in a lovely old historic building. The beer will still be wet, though. The local eating house – The Corner Kitchen and Bar – is wonderful. Great contemporary Kiwi cuisine, and intriguing art on the walls. A visit to James Wright’s sculpture studio, a few minutes’ walk down the road, provides further reward.

The landing became known as the ‘Port of Clevedon.’ It was the highest navigable point on the river for sizeable boats. Nevertheless, it was common for the earliest settlers to walk to Auckland via Howick, carrying produce to sell and bringing supplies back.

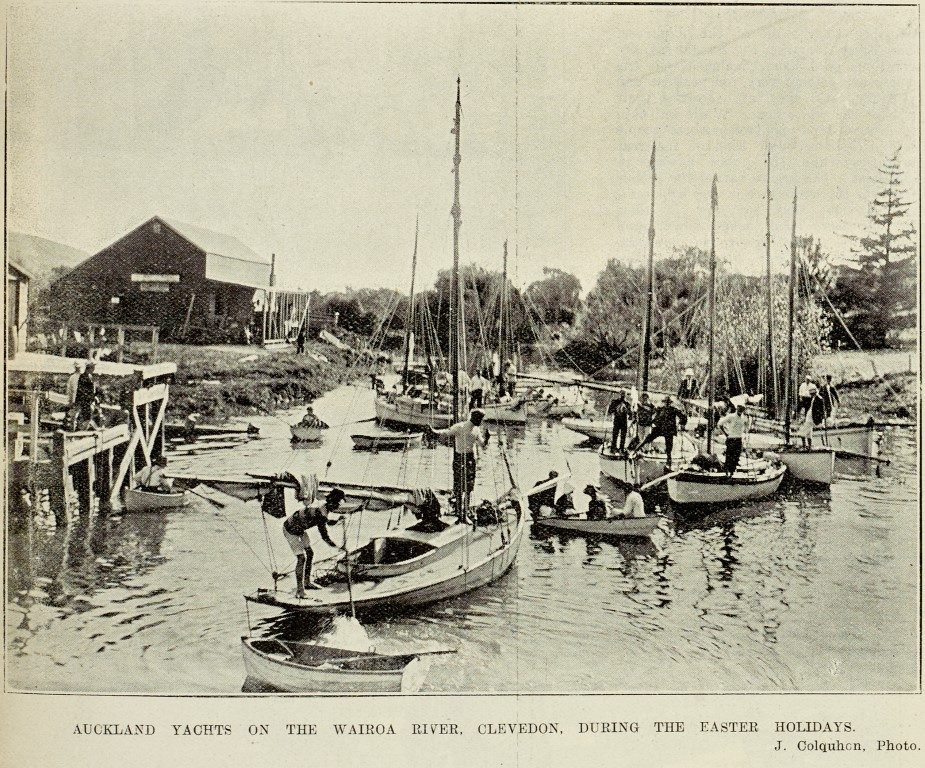

Private craft including rowing boats used the river route to Auckland, some offering lifts when they could. In 1865, Messrs Thomas Hyde and George Couldrey began a more regular service using the 15-ton cutter Rapid.

In 1897 the SS Hirere was built for the Clevedon Steam Navigation Company. It was a small ship, about 15m long, designed for narrow waterways. Many locals were shareholders in the company and they insisted on an improved and more consistent service. After 30 years on the job, the Hirere made her last trip up the river in 1927.

Since 1863, four bridges have crossed the Wairoa River at the spot just above the wharf. Previously, shingle crossings upstream and beyond tidal influence were used. Just a little way further upstream, the Wairoa is the closest trout stream to Auckland. It’s also the river that tumbles over the Hunua Falls.

The first bridge at Clevedon was a wooden truss design which conked out in 1880-81 was replaced by the second. This bridge was washed away by a 1907 flood. It was found several miles downstream and towed back (!) to a temporary position until replaced by a one-lane concrete structure in 1908.

This was one of the first reinforced concrete bridges built in New Zealand, and judging by how people dressed up for it, opening day for this bridge was quite an event. However, it really wasn’t built with cars in mind and was eventually replaced by the present bridge, which opened in July 1966.

A short walk from the wharf is the delightful local museum in the historic McNicoll Homestead. The good folks behind the desk are always good for a yarn. But don’t enquire too closely about the framed family trees of the district just inside the front door: apparently some locals are not happy about the relative prominence of some names.

Another framed item of curiosity are the silk knickers worn by a society bride way back when. Like so many small museums of New Zealand, the McNicoll Homestead is a treasure trove of unexpected stuff. A great library of historic pictures, models of the river steamers, and a re-creation of a period kitchen and its wares.

Heading back, the old boats sigh in our wake. The netmending man nods. Lights a new fag. The royals see us off at the river mouth. History is over for the day. Tom and Huck will have to go latent for a while. Not for long though. There’s another adventure lurking around the next river bend.